What Blair should have said to Hitchens

- FATHER RAYMOND J. DE SOUZA

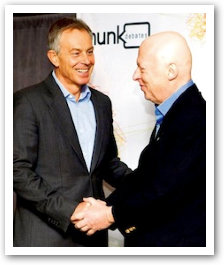

Toronto glittered last week at the debate between Tony Blair and Christopher Hitchens on whether religion was a force for good in the world.

|

Blair is now a Clintonesque mega-celebrity, but he was no match for Hitchens, who is more intelligent, articulate and funny. More to the point, Hitchens has been a noisy atheist for so long that he could make his case asleep or awake, drunk or sober, ravaged by cancer (as he is) or in the pink of health.

Still, Blair's effort was desperately weak. Blair argued that while many horrific things had been done in the name of religion throughout history, many good things were done today by people who were inspired to do so by their faith, even though it was certainly possible to do good things without faith. It was a sand-castle of concessions and caveats and cautions, and consequently it was child's play for Hitchens to demolish it.

Which was a shame, because Tony Blair might have appealed to any number of convincing arguments, challenging an audience that apparently found atheism to be alluringly chic.

The resolution was geared toward the social utility of religion, so Blair could have made his dominant argument more forcefully. There is abundant data on civic participation and charitable giving that indicate religious practice is positively correlated with both. The history of education, both elementary schools and universities, health care, social assistance and overseas aid is dominated by religious institutions.

He should have insisted that the heroism of the saints is surely the standard by which to measure religion, rather than the wickedness of the sinners. To measure something by its adherents is the fair standard.

In terms of politics, religion has been the primary check on totalitarianism, for it places a limit on state power – which is why tyrannical regimes always seek to control or eliminate religion. Indeed, the lesson learned from the French Revolution onwards is that the first order of business for formally atheistic regimes is mass slaughter. In contrast, Blair might have observed that the principal force of political liberation in the last century has been explicitly religious in character, from the U.S. civil rights movement to the peaceful overthrow of the Soviet Empire; and elsewhere, in places as different as India, the Philippines and East Timor.

Despite the resolution's focus, Hitchens was eager to engage Blair on what he called "metaphysics." Blair should have been happy to follow, for the first good of religion is the acknowledgment that God exists, and the offering of fitting worship to Him. While Hitchens contended that this made man humiliatingly servile, Blair could have countered that it makes man humble, aware of his limitations, accountable for his actions, and inclined to the service of others. Man does not need metaphysics to grasp for power in the search for domination – nature is obviously red in tooth and claw. It is supernatural revelation that provides the possibility of replacing power with love, domination with service, as a worthy human goal.

He should have insisted that the heroism of the saints is surely the standard by which to measure religion, rather than the wickedness of the sinners. To measure something by its adherents is the fair standard. |

Toward the end, Hitchens attempted to provide Blair with better arguments than he had been able to offer – and spoke of the universal human experience of beauty, whether natural or manufactured. In the face of a landscape, or profoundly moving music, or sublime architecture, man is moved by the "numinous, the transcendent, the ecstatic." Blair should have countered that in the face of those things that are beautiful and yet change, it is necessary to ask from whence they came – if not from the One who is beautiful and changeth not. That's basic St. Augustine.

In entertaining the argument from beauty, Hitchens unknowingly stumbled into the territory of Pope Benedict, a man for whom Hitchens harbours a special hatred. Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger once claimed that the Church had only two convincing arguments for the truth of the Gospel: the lives of the saints in her midst and the art which she has inspired. The good and the beautiful testify to the truth. Hitchens himself illustrates the principle in reverse, for his rejection of the Gospel has led him to contempt for the good, hence his vitriolic attacks on Mother Teresa.

But give Hitchens his due. He made his argument, and part of Blair's as well. But if he wants to return to Toronto for a better debate, he would find more worthy interlocutors in these pages. Just to name three, Barbara Kay, Rex Murphy and Conrad Black would all prove more able than Tony Blair did.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Father Raymond J. de Souza, "What Blair should have said to Hitchens." National Post, (Canada) December 2, 2010.

Reprinted with permission of the National Post and Fr. de Souza.

photo: Reuters

The Author

Father Raymond J. de Souza is the founding editor of Convivium magazine.

Copyright © 2010 National Post