How Unbelief Can Survive the Miraculous

- ROD DREHER

In human nature, we have powerful reasons to reject belief in ideas that shake up our preferred credo.

|

Cognitive psychologist Steven Pinker and novelist-philosopher Rebecca Newberger Goldstein are, as Salon.com once called them, "America's brainiest couple." They are also atheist materialist – that is, they do not believe in God, nor do they believe in the soul. Yet in that 2007 Salon interview, they both admitted that if they were to see evidence of the paranormal – communication with the dead, say – that could not be explained naturalistically, then the materialist stance on the mind-brain question would instantly collapse.

I admire their willingness to identify conditions under which a core belief would be falsified. Atheists who say that there is no evidence that could shake their materialism have gone beyond the bounds of science, and have taken a religiously dogmatic position. Not so Pinker and Goldstein, who are in theory open to being wrong.

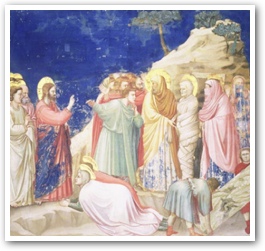

In truth, I doubt very much that anything could sway the minds of these eminent intellectual unbelievers. In human nature, we have powerful reasons to reject belief in ideas that shake up our preferred credo. In the Gospel story of Lazarus, a crowd of Jews watched Jesus raise his friend from the dead. Many walked away believing in Jesus, but others ran to the Pharisees and said, "Look, we have to stop this guy. If he keeps this up, everybody is going to follow him, and we'll lose everything."

Notice that those who sought the Pharisees' help didn't deny that Jesus raised a man from the dead. They only focused on what they stood to lose if others who saw this miracle believed that the man who worked it was who he said he was. Their reaction calls to mind the final stanza of the great W.H. Auden poem, in which the poet meditates on a famous painting and the light it sheds on humanity's tendency of humanity to ignore or dismiss startling events that would unsettle our convictions:

In Breughel's Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away

Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may

Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry,

But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone

As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green

Water; and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,

had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.

It's like that with us, isn't it? Christians today marvel at the shortsightedness of those pious Jews, but those frightened men's concern is entirely understandable.

When confronted with signs and wonders, it is not easy to discern the meaning of the events. If one is too credulous, one risks being led astray from the truth (as the saying goes, you don't want your mind to be so open that your brains fall out). If one is too skeptical, one risks persisting in error. Twenty years ago, I experienced a true adult conversion to Christianity, after experiencing an answer to prayer so unexpected and inexplicable that it would have taken more faith to dismiss it as a coincidence than to believe it was a communication from God. I chose to believe, for once, and it changed my life.

In the years since, I have witnessed on three occasions, in the presence of friends who were not believers, or at best nominal believers, events that presented physical evidence of the spiritual realm – and in one case, of the bona fide miraculous. All three cases were instances that would have easily met Pinker and Goldstein's criterion for collapsing materialism. In no case did the friends of mine who were witnesses have deeply thought out convictions about atheism and materialism; indeed, I suspect none would have called themselves atheists.

Yet in only one case did the friend change her life based on what she saw. In fact, the friend who experienced the most thrilling miracle of them all – I saw it too – was the one who was least affected by it.

But what a challenge the Lazarus story poses to us today: to work toward making sure we are not the kind of people who have somewhere to get to, and sail calmly on, oblivious to the call of the miraculous in our everyday lives. |

Why not? The answer is that in most cases, we only believe what we are prepared to accept. As a young agnostic, I thought if only God would give me a sign, some evidence of His existence, I would believe. I know now that I was lying to myself. To have accepted God would have required relinquishing my moral autonomy – and that's not something that I, as a strapping American college boy, was prepared to do. But I didn't know it at the time. I considered myself a paragon of clear, rational thinking.

Experience has a way of humbling one, but even today, there are certain things that I would reject because of an a priori religious commitment (though I no longer flatter myself, as do many materialists, that I am thinking objectively). If a wonderworker appeared on the streets of my town today and raised a man from the dead in the name of Shiva (for example), like all faithful Christians, I would be theologically obliged to reject the alleged miracle as a fraud or the work of the devil.

It is not so difficult for me to relate to the fear Jesus's miracles caused among those with the most invested in maintaining Jewish orthodoxy. Indeed, given my own priorities and temperament, I would be more likely to go running from the site of Lazarus's resurrection straight to the chief priest, demanding that he do something about this occult crackpot Jesus. And I am reasonably certain that I would have been standing in the crowd yelling, "Crucify him!", for the sake of protecting the integrity of that which I valued more than my own life: my faith.

How blessed I am, then, to follow a man who said, as he was dying on the cross, "Forgive them, Lord, for they know not what they do." But what a challenge the Lazarus story poses to us today: to work toward making sure we are not the kind of people who have somewhere to get to, and sail calmly on, oblivious to the call of the miraculous in our everyday lives.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Rod Dreher. "How Unbelief Can Survive the Miraculous." Real Clear Religion.org (April 18, 2011).

Reprinted with permissio of RealClearReligion.org and the author, Rod Dreher.

The Author

Rod Dreher is a senior editor at the American Conservative. He is an Orthodox Christian and the author of The Benedict option: a strategy for Christians in a post-Christian nation, How Dante Can Save Your Life: The Life-Changing Wisdom of History's Greatest Poem, and Crunchy Cons.

Rod Dreher is a senior editor at the American Conservative. He is an Orthodox Christian and the author of The Benedict option: a strategy for Christians in a post-Christian nation, How Dante Can Save Your Life: The Life-Changing Wisdom of History's Greatest Poem, and Crunchy Cons.