The Church and the Beginning of it All

- ANTHONY ESOLEN

The man of faith knows that the questions he asks of the universe admit of a solution, because they have been posed to him by the Lord of that universe.

Join the worldwide Magnificat family by subscribing now: Your prayer life will never be the same!

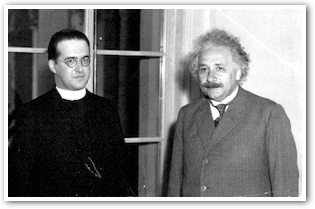

Monseigneur Georges Lemaître

Monseigneur Georges Lemaître and Albert Einstein

Once, when I was a young professor visiting my kin in Italy, I was showing a group of boys, with a broomstick and a soccer ball, how to play baseball, when some teenagers sauntered along and interrupted the game. They saw that I was "the American" who had come to the village, and they wanted to talk. When they heard that I was a professor, one of the boys — after the manner of boys everywhere — decided to get his friend into trouble and to enjoy the spectacle.

Professore, he said, cocking his thumb sideways toward the friend, Pietro qui non crede in Dio — Peter here doesn't believe in God!

"And so what does Peter believe in?" I asked.

Io credo nella scienza, said the lad, proudly. I believe in science! And then he added, Il Big Bang!

Well, that prompted a chat, in which it became clear — comically clear, to the other boys listening in — that Peter didn't know the first thing either about the Big Bang or about what the Church teaches regarding the beginning of the universe or about what one has to do with the other. But, aside from his scientific naïveté, Peter was in good company. Most people, and that includes most scientists, don't know anything about those last two things either.

Some professors are adolescents too

That incident reminds me of something less pleasant that happened to me later. I'd translated Lucretius' On the Nature of Things into English verse. Lucretius was a great poet and a rather poor philosopher. He was an Epicurean, meaning that he believed that the gods had absolutely nothing to do with man, that all events in the world had "rational" explanations, and that all things were essentially nothing other than their constituent parts, which were atoms of various shapes (some roly-poly, for slippery things like oil, and some spiky, for sharp things like vinegar), and empty space. And so a perfect stranger wrote to me, without introduction: "How can you have translated Lucretius and still be a religionist? Did you learn nothing from the experience?" Such are manners in our day. I filed the letter in the fit receptacle.

He specifically says that it doesn't matter to him whether you use one explanation for lightning or the movements of the stars or earthquakes or the origin of man or another, just so long as it has nothing to do with gods.

Now, the odd thing about his expression of contempt was that Lucretius himself gives the ballgame away in the supposed battle between faith and science. He specifically says that it doesn't matter to him whether you use one explanation for lightning or the movements of the stars or earthquakes or the origin of man or another, just so long as it has nothing to do with gods. But as soon as you utter those words, you cease to be a scientist. That is, you cease to confine yourself to what you can observe or measure or deduce from your observations. The claim isn't scientific but philosophical and theological. And if the truth leads you naturally toward supposing that the universe must have been created — if the science leads you to the threshold of faith — then the science must be rejected, or must be interpreted in contorted and fanciful ways so as to muddle the issue. So it is that the zoologist and village crank, Richard Dawkins, has said that if he saw the arm of a marble statue move, he'd prefer to believe that the atoms of the marble had coincidentally, in their constant random motion, all lined up in one direction, rather than to believe that a greater Power had moved the arm at will.

He's only doing what the Soviet physicists did when they first confronted the Big Bang theory. They knew that it sounded suspiciously like creation. So they rejected it. Now then, they had to come up with some explanation for what we see about us, and so they invented the Steady-State theory of the universe, which, since the universe seemed to be expanding, meant that particles had suddenly to appear — ping! — from absolutely nothing, and to remain in existence as such. The Nazis for their part called the whole thing "Jewish" science, thinking of the Book of Genesis, and Albert Einstein.

Science and the Catholic priest

Yet Einstein was not the first man to suggest that the universe sprang into its glorious array from a single point. That man was his esteemed colleague, Georges Lemaître (1894–1966), who made the proposal in a brilliant paper published in 1931. Lemaître was a Jesuit priest. Einstein had believed, along with the consensus of scientists at the time, that the universe had existed indefinitely far back in time. But the contradictions between that position and what Einstein and others had themselves observed and deduced — for instance, Einstein's famous formula uniting energy, mass, and the speed of light — led Father Lemaître to formulate the most significant cosmological hypothesis in modern science. When Einstein learned of it, he declared it to be beautiful — which was his genial way of saying that it had the persuasive simplicity of truth.

Now, it is important to keep in mind that Father Lemaître was not searching for scientific proofs of the existence of God. Nor did he claim to have found such. One step before the threshold is still not inside the house. But he was also not a Jesuit priest who happened to be a scientist, keeping his theology in one compartment and his science in another, and never the twain should meet. That would still not describe the relationship aright. For the man of faith knows that the questions he asks of the universe admit of a solution, because they have been posed to him by the Lord of that universe, who is at once hidden wholly in every infinitesimal moment of time and extension of space, and yet indirectly manifest in the world's magnificent beauty and order. When we approach both theology and science with the proper reverence and deference to the methods and subjects and ends proper to each, we shall respect both the integrity of creation and the transcendence of God.

That means that we will not foolishly seek for a reduced god, a familiar Mr. Zeus, let's say, who tweaks the world from the beginning and then goes about his other business. But we will also remember why we look to the heavens at all. Computers and cattle do not do so. Why should we? What or whom do we seek? Here I can do no better than to quote Father Lemaître himself, from The Primeval Atom:

We cannot end this rapid review which we have made together of the most magnificent subject that the human mind may be tempted to explore without being proud of these splendid endeavors of Science in the conquest of the Earth, and also without expressing our gratitude to One Who has said: "I am the Truth," One Who gave us the mind to understand him and to recognize a glimpse of his glory in our universe which he has so wonderfully adjusted to the mental power with which he has endowed us.

Thou hast made him little less than the angels

I might conclude here, but I am wary, lest I give the impression that we Catholics are rushing to the fore with our arms in the air, waving and crying, "Please pay attention to us! We can be scientists too!" Of course we can be and we have been, and among the greatest — Father Lemaître himself received from Villanova the Mendel Medal for outstanding scientific achievement, an award named after the father of the science of genetics, the monk Gregor Mendel. But that is not really my point.

The poor addled Pietro was using the Big Bang theory, which he understood even less than an Italian understands baseball, as an excuse not to think.

Father Lemaître held a doctorate in physics from MIT. But he also held degrees in mathematics, philosophy, and theology. And, along with all his fellow priests, he regularly contemplated the mystery of the Incarnate Word, made present in the Eucharist under the species of bread and wine. He took to heart the words of Jesus, "Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the earth." In him, and I am speaking about the core of his being, the search for truth was the search for Christ.

The poor addled Pietro was using the Big Bang theory, which he understood even less than an Italian understands baseball, as an excuse not to think. The Lucretians in our midst do the same: if they can be persuaded that they know where a man comes from, so long as the answer does not have "God" in it, they need not think too much about what a man is. They have the adverb "only" always at their call; the world is only this, man is only that, morality only a social construct, life only a certain kind of organized motion, death only its cessation. Much virtue in only. But the scientist who is Catholic affirms instead, "The Lord, and all of the world besides!" He cries out with the psalmist: "O Lord, our Lord, how majestic is your name in all the earth!"

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Anthony Esolen. "How the Church Has Changed the World: The Church and the Beginning of it All." Magnificat (November, 2014): 215-219.

Anthony Esolen. "How the Church Has Changed the World: The Church and the Beginning of it All." Magnificat (November, 2014): 215-219.

Join the worldwide Magnificat family by subscribing now: Your prayer life will never be the same!

To read Professor Esolen's work each month in Magnificat, along with daily Mass texts, other fine essays, art commentaries, meditations, and daily prayers inspired by the Liturgy of the Hours, visit www.magnificat.com to subscribe or to request a complimentary copy.

The Author

Anthony Esolen is writer-in-residence at Magdalen College of the Liberal Arts and serves on the Catholic Resource Education Center's advisory board. His newest book is "No Apologies: Why Civilization Depends on the Strength of Men." You can read his new Substack magazine at Word and Song, which in addition to free content will have podcasts and poetry readings for subscribers.

Copyright © 2014 Magnificat