'It would compromise my very humanity'

- FREDERICA MATHEWES-GREEN

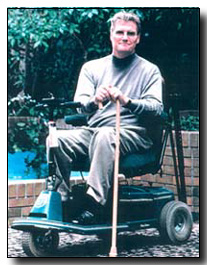

Some say Mark Pickup's multiple sclerosis could be wiped away through what scientists learn from testing embryonic stem cells. So why does he travel the country to speak against that research?

|

Mark

Pickup |

There's a problem. The audience, a few hundred doctors and nurses, is clustered along conference tables and in rows of chairs all around the room, waiting for the next speaker. But he's still a good 20 feet from the podium. Between him and that microphone, up on a raised dais, is a short flight of stairs. And that's the problem.

Folks from the college are setting up a sheet of embossed steel to be laid over the stairs. But it's angled too steeply for someone in a motorized wheelchair to ride up, and when the top rests on the platform the bottom doesn't reach all the way to the floor. In the end, Mark Pickup manages to climb the stairs with the help of a cane, while others pull his wheelchair up the incline.

"Assisted suicide means excluding people. And I don't want to be excluded. I want to be included," Pickup says in a firm, clear voice. As with actor Christopher Reeve, the use of a wheelchair does nothing to diminish Pickup's noble bearing or contradict his rugged profile. "I want life with dignity, not death with dignity. After almost 18 years with this disease I have come to the conclusion that we do not bestow dignity on a person by injecting them with poison when they're at their lowest point.

"Generally speaking, people don't die with any more dignity than they have lived with. Dignity is not an event. It is a process."

Twenty years ago, Pickup, now 48, was not just a member of the able-bodied in-crowd, he was out in front: skiing, swimming, running, playing guitar, "a very active dad" to his two young kids.

Then one day "I went dead from the waist down," Pickup told Citizen. There followed two years of tests and treatments, ups and downs. Finally, in 1984, there was a diagnosis: multiple sclerosis.

The disease is "raucous," he says, tantalizing victims with remissions, then demoralizing them with relapses. Pickup and his wife, LaRee, had to give up their split-level home; the stairs were unmanageable. He lost his job with the Canadian Civil Service. More physical degeneration was yet to come. LaRee, soft-spoken with warm brown eyes, says, "If someone had told us then that we would be at this point today, I would have been scared to death."

Pickup agrees. "If someone had said to me that I would go on this roller coaster of health, that my legs would be weak, I would lose use of my arm, that I would go incontinent, that I would have visual problems, I would have said that there is no quality of life.

And if they had said, 'There's a wheelchair in your future' " he pauses and gestures firmly "I would have said 'No. No. No.' "

However, as Pickup likes to say, "Quality of life is a moving target." When disease does damage that seems unbearable, when it strips away abilities that seem essential, it reveals that they weren't essential after all. The unbearable is met with strength equal to the burden. Standards of what constitutes "the good life" continually readjust. "What gives my life quality today is not being able to run or swim or ski," Pickup says. "It's being able to love and to be loved, to think that I am still making a contribution to the world, whether I am or not."

Too often, someone entering disability feels shattered, and suicide assisted or not looks like a release. Pickup cites a study by a British Columbia rehabilitation specialist, Walter Lawrence: Among people with high-lesion spinal cord injuries, 90 percent want to commit suicide. Five years later, only 5 percent contemplate suicide. Quality of life is a moving target.

Though he's a 20-year veteran of the pro-life movement, Pickup's situation has led him to concentrate increasingly on disability and euthanasia issues. It's work that others toiling in the vineyard particularly admire.

"Mark Pickup is one of the most eloquent voices in North America arguing on behalf of the inherent equality of all human life," says Wesley J. Smith, a prominent commentator on bioethical issues and author of Culture of Death. "His nobility, his passion, his vision, are a badly needed antidote to those voices who oh so smoothly argue that some lives are expendable. We ignore Mark Pickup at our own peril."

John Kilner, president of the Center for Bioethics and Human Dignity, agrees. "Mark Pickup brings a rare blend of experience, heart and mind to today's pressing issues of life and health in a God-honoring way. There is real passion and integrity in what he says. I thank God for his courage and wisdom."

| As he settles back into the chair and begins his speech, Pickup doesn't refer directly to this obstacle. Instead, he starts with the topic of euthanasia. The stretch isn't as broad as it seems. Pushing the eject button on disabled and elderly humans is the natural ending to a sentence that can begin with something as unintentional and apparently benign as a dais barricaded with stairs. |

Fighting temptation

These days, another facet of the life issues is drawing Pickup's attention: stem-cell research. In an essay in Canada's National Post, he described how German researchers had experimented with embryonic stem cells in animals and achieved what they termed a "critical breakthrough" for the treatment of debilitating diseases like Parkinson's and MS. Other scientists had announced similar results, and stem-cell transplants had been performed on about 50 people with MS.

"For years, I have lived with the fear that my next address may be a nursing home," Pickup wrote. "I have been haunted and taunted by the thought that I may become one of those sad lumps of humanity propped up in wheelchairs, passing monotonous days, staring out nursing-home windows hoping for a visitor."

The hope that a medical treatment could reverse that, could enable him to dance with his wife, ski with his son or walk his daughter down the aisle, is nearly irresistible. After all, embryonic raw material is plentiful: Embryos wait in fertility-clinic freezers for parents who don't intend to implant them, and they will just be thrown away. A research lab can even mix sperm and eggs in a petri dish and create its own handy mbryos. Or, by destroying the nucleus from an egg and inserting material containing the patient's own DNA, a lab can create an embryo clone all the better to harvest stem cells that perfectly match its donor's.

However, Pickup concludes, the cost is too high. "I'd have to . . . look the other way from the reality that my deliverance was gained at the expense of another life." A cure gained by destroying embryonic life would violate his integrity, his deepest convictions. "To gain my freedom from disease, I would become more wretched by accepting the fruits of robbing another of life, existence and a place in the world. No! The cure would only increase the torment." As Pickup notes, "It's like a Stephen King novel."

Some celebrities, like Reeve and Parkinson's sufferer Michael J. Fox, have lobbied for embryonic stem-cell research, but others are asking the same questions Pickup does. File it under "strange bedfellows": While Nancy Reagan presents her husband Ronald as one who could benefit from such research, gay journalist Andrew Sullivan says he would refuse the cells as treatment for his own HIV.

"If my life were extended one day at the expense of one other human's life, it would be an evil beyond measure," Sullivan contends. And the trade-off is not only evil, but uncalled for even on the most utilitarian grounds. Mounting evidence suggests that stem cells from adults, or from newborns' umbilical cords, may be even more effective than stem cells from embryos.

But to Pickup, whether that research pays off isn't the most important issue. Even if embryonic stem cells were his only chance for a cure, it's a chance he'd refuse to take.

Disabled outside, healed within

Pickup began to gain the moral language to deal with suffering a few years before he became ill. "I converted in 1980," he says. "I had a problem with alcohol. No, I was an alcoholic."

Though he had not been practicing his faith seriously, he could not shake the convictions instilled by devout and honorable parents throughout his childhood. "I had been given so much as a child, and was I going to bestow an alcoholic's life to my children? Tell me how that fit," he says. "I had been given so much that I of all people should give my children a good upbringing. When I realized 'you don't have control of this at all,' the Lord led me out of alcoholism."

LaRee was not a believer and wasn't sure how much she liked this change. She laughs as she describes asking herself, "Which is worse, having the pastor over for dinner, or having Mark booze out?" Pickup would call her over when he was reading the Bible "and I'd go 'Oh, brother,' " she says, rolling her eyes. Eventually she started sneaking looks at the Scriptures when he wasn't around. "I didn't want him to know he was having an influence on me."

When the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis was delivered, LaRee was a new Christian with a still-wobbly faith. She considered divorce: "Do I want this? Should I run now?" In fact, Pickup says, 80 percent of MS patients see their marriages fall apart. But LaRee already had seen the effects of divorce on her four siblings and her parents. "Do you know anybody who went through a divorce and it actually made things better? Very few. Besides, do people think they can run away and never have a health problem? It's going to come one way or another."

Pickup takes seriously the idea of a "watershed moment," a point in life when a decision changes everything. Deciding against divorce was a watershed for LaRee, he says. If she had gone that direction, "it would have changed who she is. And if I accepted fetal stem-cell therapy, it would change who I am. Is it tempting? Sure it is. But it would compromise not just my Christianity, but my very humanity. "When I stand before the Lord and He explains why this was allowed . . ." Pickup hesitates, then starts again. "Some men are guilty of sins of the flesh, and I'm guilty of the sin of pride. If MS is what it takes to root that sin out, so be it.

"Today my life is richer, not in spite of the MS, but because of it."

![]()

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Frederica Mathewes-Green. "'It would compromise my very humanity'." Citizen (2001).

This article appeared in Citizen and is reprinted with permission from Focus on the Family.

The Author

Frederica Mathewes-Green is a wide-ranging author. She has published 9 books, including Facing East: A Pilgrim's Journey into the Mysteries of Orthodoxy, The Illumined Heart: The Ancient Christian Path of Transformation, At the Corner of East and Now, The Illumined Heart, The Open Door: Entering the Sanctuary of Icons and Prayer, and Gender: Men, Women, Sex, and Feminism. In the past, her commentaries have been heard on National Public Radio's All Things Considered and Morning Edition. Her essays were selected for Best Christian Writing in 2000, 2002, 2004, and 2006, and Best Spiritual Writing in 1998 and 2007. She has published over 700 articles. She lives in Linthicum, Maryland, with her husband Fr. Gregory, pastor of Holy Cross Orthodox Church. They have three children and three grandchildren.

Copyright © 2001 Focus on the Family