How the Church Has Changed the World: The Father of a Nation

- ANTHONY ESOLEN

"What are you doing, Medicine Man?"

Join the worldwide Magnificat family by subscribing now: Your prayer life will never be the same!

The warrior, hardly more than a boy, sat cross-legged on the sand. He wore but a breech-cloth, and his strong arms and legs gleamed like bronze in the sun. The man he addressed was pale by comparison, though the many months outdoors had dried his face and hands to a leathery brown. He was a bit of a swayback. Just now he was leaning over the sand on the beach, tracing out strange lines and curls, lost in thought:

Consolavas benigno os bons pais que gemiam,

Restituindo às mães os filhos que perdiam.

"I'm making a song," said the man.

The boy knit his brows. Songs were wonderful things, like magic, like medicine. They could also be dangerous. "You are making a song to kill us!" he cried.

At that the man looked up and laughed. "No, Caua," he said, using the native Tupi language he had learned so well. "This is what it means. The mother is speaking to her son, who is God. She asks him to be kind, and to comfort the good mothers and fathers who weep, returning to them the children they have lost."

Losing children was a common enough thing. And worse. Caua knew an old woman who asked for her favorite tidbit while she lay dying: children's fingers. "Why do you make this song, Medicine Man?"

"To sing to the great Mother of God, Caua. And for you too."

"For us? Are we lost?"

"Not anymore," said the man, laughing.

On the road to São Paulo

The man, José de Anchieta, recalled the time when he first stood on the cliffs overlooking the Atlantic Ocean, cliffs that rise two or three thousand feet along the coast of Brazil. The place stank of dead fish drying in the summer sun, stranded there when the flooding River Tietê returned to its usual banks.

Dominus vobiscum, said the celebrant.

Et cum spiritu tuo, said José.

It was January 25, 1554, the feast of the Conversion of Saint Paul. There on the heights, set at some distance from the Portuguese colonists, he and twelve other Jesuits set up their first mission, their first college. Thus did they found the settlement of São Paulo, today the most populous city in the western hemisphere.

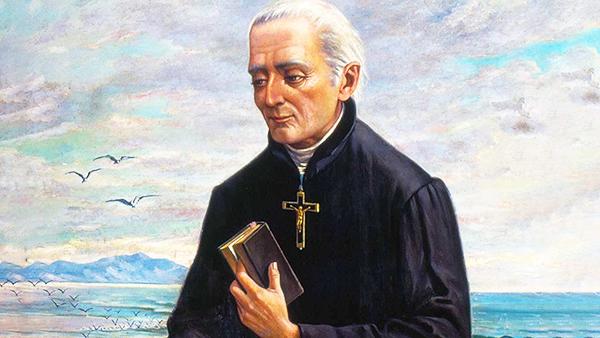

I'm looking at a painting of the event, by Antônio Parreiras. The priest faces a small congregation, just the other Jesuits and an old bearded European. Anchieta stands nearest to us, reading from his missal. A long-haired native, stout and muscular, looks on with folded arms and one foot forward. Some naked natives in the distance seem to be approaching.

"José," the Jesuit provincial had said, "you are the best among us with languages." José nodded. It was true. He'd grown up on the Canary Islands, speaking Spanish, not Portuguese. He was a master at Latin, which he taught to the novices.

"You must teach us how to speak to these people." So he did.

Savages here and savages there

José Anchieta became the great apostle to Brazil, the father of the nation. Here some reader may cry, "But the Portuguese went there to establish colonies." True enough. That's the rule in human history. People see a bountiful land and they go there, especially if they believe they can use it in ways the natives cannot. Migrations have always meant war. Canaan was not empty when the children of Israel arrived.

What is not the rule in human history, what is inexplicable outside of the faith, is what José Anchieta and his fellow Jesuits did. He had not yet been ordained a priest, but he burned with the fire of the Good News. He wanted to save souls. To do that, he had to know the people as best he could. He studied their ways, without contempt but also without sentimental indulgence, so that to this day his reports to his superiors in Portugal are invaluable works of anthropology. He compiled a dictionary and a grammar of the native Tupi language, so that Tupi and not Portuguese became the common tongue for communication between the Europeans and the various native tribes. He taught the natives how to work the land, so they would not be reduced to serfs on the Portuguese plantations. That often put him at odds with the Portuguese settlers, but so it was.

He studied their ways, without contempt but also without sentimental indulgence, so that to this day his reports to his superiors in Portugal are invaluable works of anthropology.

When we saw him scrawling poetry on the beach, it was because he had given himself as a hostage to the Tamoya, who were at war with the Portuguese and their allies among the Tupi. The Tamoya honored his courage. That was not wholly to his advantage, since it meant that, despite his lean and awkward form, they might kill and eat him to absorb that courage. They liked to fatten their human prisoners. Anchieta was a hostage long enough to compose, in his mind, a four-thousand-line poem in Portuguese, on dramatic moments in the life of the Blessed Virgin. He wrote the words in the sand as he composed them, to remember them when — or if — he would return to his brothers.

As for the cannibalism, the natives fed on man-flesh, said a Dutch explorer, not for hunger, but for inveterate hatred. "This day," he heard one warrior cry, "before sunset, your flesh shall be my roast meat!" Many of the Portuguese settlers believed that nothing could be done for a people so savage. But Anchieta and his fellow Jesuits took a dim view of the sins of the Portuguese, too, so that sometimes it seemed he was caught between savages on each side.

Still, it was a shock to him to see for the first time a cannibal feast, on Corpus Christi, of all days. The Tupi were glad to see him and made merry, eating and drinking and dancing, when one of them boasted that he had recently eaten a Portuguese slave, and called for one of his wives to fetch a leg he'd saved, to make a flute out of the shinbone. "You ate him," his friends laughed, "let us have some of him too!" So they sprinkled it with flour, said Anchieta, and gnawed away at it like dogs.

Eventually the Tamoya had to be defeated decisively in war, which Anchieta memorialized by the first epic poem written in the New World, his De gestis Mendi de Saa, on the accomplishments of Mem de Sá, the governor of Brazil. It is a remarkable work in sinewy Latin hexameters, indebted to Anchieta's vast reading in Virgil, Ovid, and Lucan, but quite original, and in part sympathetic to the people he had come to bring into the light.

For those works in Portuguese and Latin, José Anchieta is justly considered the father of Brazilian literature.

The play's the thing

Around the time that war ended, Anchieta was finally ordained a priest, and here we find him most busily at work. He had gifts both natural and supernatural. He had prophetic powers. He was sometimes surrounded by light, which he himself did not notice. He was a physician, and he taught the Tupi what he knew of the art of healing. He never rode a horse, but only walked, indefatigably, so that the path he wore from São Paulo to the principal settlement of the Portuguese at São Vicente, over forty miles away, was called Father José's Road. He could work for days without sleep. He attracted the natives by the gentle authority of his voice.

And by his playfulness, too. Pope Francis, who canonized Father José in 2014, said that the priest brought joy wherever he went. Joy is a fearful thing, said the pope. We must be brave to submit to it. Perhaps children are more apt to be taken prisoner by joy. Father José knew he should preach to the children before they fell into the savagery of their elders. He composed songs in Portuguese and Tupi, to delight them and teach them the stories of the Christian faith. He also wrote plays — think of the miracle plays of the medieval world, a vigorous and popular drama, on the lives of the saints or the Passion of Christ or the sorrows and joys of Mary. You mustn't imagine a formal stage and professional actors. Rather: bright costumes, natives in body paint, natives rattling the maracas, children kneeling roundabout the churchyard, torches, much song in both languages, and joy — the bright and mighty joy of the Gospel, victorious over the darkness of man's ancient enemy the devil. Father José did not want the children to grow up to be like their parents. He wanted the parents to grow into a spiritual childhood they had never known.

If you go to São Paulo, you can catch a play at the Father José Anchieta Theater. I do not know whether it will lift up your soul. But Father José is considered also the first great playwright of Brazil.

Saint José Anchieta died on June 9, 1597, in retirement at the seashore village of Reritiba, now called Anchieta in his honor. He is said to have converted over a million natives. I think he would have walked a thousand miles to baptize a single one.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Anthony Esolen. "How the Church Has Changed the World: The Father of a Nation." Magnificat (June 2021).

Anthony Esolen. "How the Church Has Changed the World: The Father of a Nation." Magnificat (June 2021).

Join the worldwide Magnificat family by subscribing now: Your prayer life will never be the same!

To read Professor Esolen's work each month in Magnificat, along with daily Mass texts, other fine essays, art commentaries, meditations, and daily prayers inspired by the Liturgy of the Hours, visit www.magnificat.com to subscribe or to request a complimentary copy.

The Author

Anthony Esolen is writer-in-residence at Magdalen College of the Liberal Arts and serves on the Catholic Resource Education Center's advisory board. His newest book is "No Apologies: Why Civilization Depends on the Strength of Men." You can read his new Substack magazine at Word and Song, which in addition to free content will have podcasts and poetry readings for subscribers.

Copyright © 2021 Magnificat