The Role of Christian Anthropology in Welfare Reform

- GREGORY R. BEABOUT

Past articulations of social policy have tended to ignore basic truths about the human person, leading to negative, long-term consequences for those in need. The rehabilitation of the proper exercise of human freedom is both the foundation and the goal of the future of welfare reform.

|

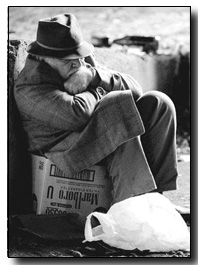

A significant part of the debate about welfare reform rests on an underlying philosophical dispute about what it means to be a human being. For example, consider the case of an administrator at a New York homeless shelter who was reprimanded for a memo in which he proposed that male residents at the shelter not be allowed to wear dresses, high-heeled shoes, or wigs. The following response came from an assistant director of the Coalition for the Homeless in New York City: "The memo is evidence of a real misconception of what the shelters are all about. Trying to curtail freedom of expression, trying to shape the behavior of clients is completely inappropriate."1

A person's reaction to that story may indicate where he or she stands on the cultural divide in contemporary American life. But it is also indicative of competing philosophies of human life. The assistant director's response that it is inappropriate for a shelter to curtail freedom of expression or make judgments about the behavior of the homeless men it serves flows from a kind of expressive individualism that provides one account of the meaning of human life. In contrast, many Americans would find it deeply inappropriate for a shelter to provide services without challenging the people it serves to improve their behavior.

Since these different responses flow from competing understandings of what it means to be a human being, and since these differences often underlie contemporary debates about welfare reform, an examination of the controversy at a more philosophical level is appropriate. After all, debates about whether homeless men should be allowed to wear dresses and wigs are likely to draw strong emotional responses, making careful analysis difficult. Further, many of the issues that will be addressed in the next phase of welfare reform namely, marriage and the responsibilities of fathers, the meaning of work, the importance of intellectual development and moral formation in children, and an elevated role for faith-based organizations and people of faith in serving the poor flow from a Christian anthropology. This includes an understanding of human beings as created in the image of God. But what exactly does it mean to say that humans are made in God's image?

The goal of this essay is to draw out the philosophy of the human person in the Christian tradition, focusing especially on the book of Genesis, and then to relate Christian anthropology to the next phase of welfare reform. First, the essay will glance at the place of Christian anthropology in the contemporary setting of what James Davison Hunter has called America's "culture wars."2 Following Hunter, I will suggest that the understanding of the human person in Christian anthropology may have more in common with the understanding of the human person in other religious traditions especially among Orthodox Jews, religious Muslims, and others than it does with the attitudes about human life that are common in liberalized and secularized elements of Christianity and Judaism. Next, the body of the essay will aim to provide a detailed understanding of Christian anthropology by drawing out the understanding of human life that is set forth in the first four chapters of the book of Genesis. This will show that, in the biblical tradition, human beings are understood as persons created in the image of God who are gendered, social creatures with inherent dignity and endowed with the capacity to know the truth and love goodness while making self-determining choices with accountability that shape their personalities, especially through their families and labor, even while being conditioned by disordered social structures. Finally, I will point briefly to seven themes drawn from this understanding of Christian anthropology and will suggest how these themes relate to the next phase of welfare reform.

Christian Anthropology and Contemporary Culture Wars

Before turning to the book of Genesis to draw out and make explicit a Christian anthropology, it will help to situate the debate about the nature of the human person in its current cultural context. After all, we are shaped to such a great extent by the religious wars of the seventeenth century that the Enlightenment response has become second nature to us. After the bloody wars of religion, many in the knowledge class began to believe that all things relating to religion were best kept private. The assumption was that religion is so utterly divisive that the best solution is to keep the public square free from religion. Further, regarding a topic such as the Christian understanding of human beings, the assumption became that there is no single Christian understanding; rather, there are various Protestant understandings, a Catholic understanding, various Jewish understandings, and so on.

During the last decade, this way of making sense of the cultural conflict in modern life has been called into question. In his 1988 book, The Restructuring of American Religion, Robert Wuthnow argues rather convincingly that the main cultural fault lines are no longer between Catholic and Protestant or between Christian and Jew, but between theologically liberal and theologically conservative.3 He claims that during the period after World War II, the institutions of American cultural life produced a new divide, where religious and denominational identity mean less than where one falls on the liberal/conservative divide that runs through the middle of Christianity and Judaism. Wuthnow observes that conservative Protestants now have more in common with conservative Catholics and Jews than they do with liberal Protestants.

This thesis is extended in James Davison Hunter's 1991 book, Culture Wars. Hunter, who prefers to call the two sides "orthodox" and "progressive," locates the source of the difference in competing notions of freedom, justice, and authority. According to Hunter, orthodox people tend to locate authority in a transcendent source outside of society and human construction. In contrast, progressives tend to use science, human reason, and contemporary culture as their sources of ultimate authority. Hunter draws on examples from contemporary American life to show that, on a whole range of issues, evangelical Protestants, traditional Catholics, and Orthodox Jews feel more comfortable with one another than they do with their progressive counterparts. And the same holds true conversely. A progressive Protestant seminarian, for example, will likely feel more comfortable with a liberal Catholic theologian or a Reform Jewish rabbi than with a self-professed "Bible-believing Baptist."

While some recent scholars have argued that Hunter's analysis of our current situation is oversimplified,4 there is, for the purpose of this essay, good reason for accepting Hunter's account. The point here is to broaden and cushion the claims that will be made below with regard to Christian anthropology.

The goal of this essay is to draw out the philosophy of the human person that is widely held in the Christian tradition and shared to a great extent by other religious traditions, and then to relate the Christian understanding of the human person to certain aspects of welfare reform. Since controversies about welfare reform sometimes rest on deep philosophical differences about the nature and meaning of human life, it is worthwhile to understand the anthropology that informs people's thinking about poverty. Of course, public policy debates about the desirability and political feasibility of particular proposals that address the problem of poverty will continue. Although some of those debates do not rest on deep philosophical differences, many of them do raise deep questions about human life. Hence, it will be helpful to have an explicit account of the understanding of the human person in order to answer certain profound questions: What is a human being? What makes for a good human life? What responsibilities do we have to one another? How shall we order our lives so that we can live well together?

To extend this argument more fully, even beyond the scope of this essay, three additional philosophical tasks are necessary. First, it is important to understand the philosophy of the human person that informs the thinking of many who oppose welfare reform. For this essay, a brief sketch of this anthropology will be useful. Of course, there may not be a unified account of the human person among progressives, but some common features of their philosophical presuppositions include the following tendencies: 1) to understand the human person primarily in material terms; 2) to think that one's state in life is determined by external conditions, especially one's environment, for which one is not necessarily individually accountable; 3) to view each individual as an isolated bearer of rights; 4) to presume that human beings, considered as individuals, are inherently good; 5) to be suspicious of communal bonds such as family, neighborhood, and church, viewing them as oppressive; 6) to believe that all claims to truth especially religious, philosophical, and moral claims are, at most, expressions of individual opinion; 7) to hold that human freedom, viewed as a basic right, consists in being able to act without external constraints as long as the freedom of others is not violated; and 8) to claim that the meaning of human life involves accumulating a wide range of experiences and then freely expressing one's responses to those experiences.

Since much of the controversy about welfare reform stems from deeper philosophical convictions about the nature of human beings, a second task involves critically evaluating the potential strengths and weakness of these competing anthropologies. But that debate, which is central to what James Davison Hunter means by the "culture wars," is both philosophical and religious. Some of Hunter's critics think that he is guilty of heightening the dispute over worldviews by lending heated rhetoric to the public discourse.5 After all, the term culture wars suggests to some that there may be a breakdown in the moral fabric of American society, causing citizens to turn against one another and resort to violence, as in Belfast or Bosnia. Such critics reason that while the old religious wars may be past, Hunter's rhetoric serves only to increase the possibility that current moral, social, and political questions will be resolved through incivility and violence rather than through a peaceful political process. This fear is heightened by the fact that, in the American political scene, describing the American setting in terms of culture wars is typically identified with Pat Buchanan, whose political voice is often perceived as caustic and shrill.

But this fear that making explicit the differences in the cultural self-understandings of various groups of Americans will lead to greater conflict seems unwarranted and is directly contrary to Hunter's goal. Hunter criticizes the tendency of the electronic media to focus on emotionally charged situations without carefully examining the philosophical underpinnings that give rise to competing emotional responses. In short, those critics who think that Hunter's analysis of our contemporary situation adds to heightened rhetoric and cultural tensions are ignoring an important part of Hunter's argument, for he goes to great length to argue that articulating our cultural differences is an important step toward civil public discourse.

Rather than aiming at heightened cultural tensions, this essay is intended to work toward an increased understanding among people who sometimes misunderstand the substance of others' views. To that end, the account of Christian anthropology that is presented here aims to be as inclusive as possible. This is not an effort to gloss over authentic theological differences. Where there are genuine theological differences among diverse Christian traditions, or between Christians, Jews, and Muslims, continued theological dialogue is needed. This account does not aim to advance one narrow understanding of Christian anthropology and thrust it upon all who identify themselves as Christians. Rather, the account presented below represents an effort to find authentic common ground for understanding what it means to be human.

Our public dialogue is deepened when an account of the human person based in the biblical tradition is presented in terms that are accessible to a wide range of citizens, including non-believers. When civic discourse is deepened in this way, our culture will be strengthened. Moreover, a deepened reflection might provide opportunities to find common ground as well as increased clarity and understanding about genuine philosophical differences that exist between Christian anthropology and alternative accounts of human life.

The Human Person in Genesis

The outline of Christian anthropology presented below seeks to follow the biblical account from the first four chapters of Genesis. Those chapters include the two narratives of the creation of the first humans, the story of the Fall, and a story about the first family after the Fall.

From the point of view of biblical criticism, it is worth noting that many scholars hold that the first two chapters of Genesis, which give two different versions of the story of Creation, come from distinct time periods.6 The first chapter (including 2:1-3)7 is widely considered to come from a later tradition that is, a tradition nearer to us. Here we find the well-known narrative of the seven days of Creation, which, since this portion of the text refers to God as Elohim, many scholars call the Elohist account of Creation. Compared to the second chapter, the first chapter presents us with, as it were, a more sophisticated theological account of both God and man. In particular, in the Elohist account of the creation of humans (Gen. 1:26-31), we find a very rich yet highly compact description of what it means to be a human being. In these six verses, we find many essential truths about human beings. Over the centuries, these verses have provided profound inspiration for countless thinkers who have attempted to understand what it is to be human. These verses will provide the basis for the Christian anthropology presented below.

The second account of Creation, found in Genesis 2:4-25, is considered by many scholars to stem from a much older oral tradition. This tradition is usually called Yahwist because God is referred to by the name Yahweh in these portions of the text. In English translations, this way of referring to God is often translated as "the Lord God." The story of Creation presented in the Yahwist tradition the so-called second account of Creation is deeply connected with the story of the Fall presented in the third chapter of Genesis, as well as with the story of Cain and Abel in the fourth chapter. In these chapters of the text, the writing contains many elements that seem almost primitive to us. For example, God is presented in very anthropomorphic terms. He creates Adam by breathing into his nostrils (2:7), and he creates Eve by taking one of Adam's ribs (2:22). In a similar way, in the story of the Fall, the anthropomorphic qualities of God may strike us as archaic. For example, Adam and Eve "heard the sound of the Lord God walking in the garden" (3:8).

These two traditions complement one another by offering alternative points of view. The Elohist account of Creation provides what may be considered, in a certain sense, an account of the creation of humans from the outside. The main action in the narrative is taken by God, and human beings are presented as objects of God's creation. In contrast, in the older Yahwist tradition including the so-called second Creation account of chapter two, as well the story of the Fall from chapter three and the story of Cain and Abel in chapter four the focus is on the action of the human beings in the narratives. We see them in conversation with God, with each other, and with themselves. These stories provide deeper insight into some of the interior aspects of human life since they provide insight into the human person's subjective self-awareness.

From these two viewpoints, the biblical account treats both objective and subjective aspects of human life. The human person is understood as a physical object in the world but also as a subject with an interior awareness of himself. Because the Elohist account of Creation, though held by many scholars to be chronologically later in derivation, gives such a rich theological presentation of the essential truths about the objective character of the human person, the outline below will focus on Genesis 1:26-31. And since the narratives from the Yahwist tradition (found in chapters two, three, and four) complement this account by bringing to light key aspects of human subjectivity, the narratives in the second, third, and fourth chapters will be used to fill in some of the additional elements of the biblical account of human life.

Creatureliness: "Let us make man..." (Gen. 1:26)

The Elohist account of the creation of human beings presented in the first chapter of Genesis is part of the story of the creation of the world. After tracing the narrative of God's creation of light, land, vegetation, the sun and stars, the birds and fish, and the animals of the earth, the text turns to the creation of the human being: "Then God said, 'Let us make man …'" (1:26). The human being is presented here as a "creature," made, in many ways, like the other wonders of creation. However, in the verse that precedes the creation of human beings, after God creates the other animals, there is a kind of theological pause. "And God made the beasts of the earth according to their kinds and the cattle according to their kinds, and everything that creeps upon the ground according to its kind. And God saw that it was good" (1:25). It is as if this pause signals that God is waiting as he decides to create humans.

Like the other creatures of the earth, we are physical beings, living animals with the limitations that come with animality. This aspect of our humanity, our creatureliness, is also captured in the so-called second story of Creation from the Yahwist tradition: "The Lord God formed man of dust from the ground" (2:7). Several features of creatureliness can be inferred from the text of Genesis. Like other animals, human beings are animals of the earth made of dust, so to speak. We depend on the earth and on all of creation to sustain us. Being a physical animal implies that we have physical needs: for food and drink, for shelter and protection. As physical beings, we are situated in a particular place in space and time. Our physical nature also reveals our radical contingency. We depend on all sorts of things in order to exist. The fact that we need air to breathe implies that we need a healthy environment, including the atmosphere of the earth and the warmth of the sun. Were our environment to be disrupted, our physical existence would be vulnerable even to the point of our physical death. In this sense, we did not create the conditions that are needed to sustain our lives. We are creatures among the other wonders of creation.

Not only does our physical existence depend on the continued stability of our physical environment, but we also depend on a stable social environment. As animals, we need water, food, and shelter. In order to acquire the material goods that satisfy these physical needs, we rely upon the cooperation of others and the help of God. In our contemporary setting, it often takes substantive reflection to realize the degree to which we depend on others. Consider the examples of driving an automobile or playing a video game. In each of these experiences, one can get the feeling of being in absolute control. For example, a well-designed car can give the driver the sense of being in charge of the world. But this feeling of ultimate power is, in fact, illusory. Upon reflection, we recognize that driving a car demonstrates the dependency of our creatureliness: We depend on countless others to design and build both the car and the roads on which we travel. Others drill, refine, transport, and sell the gasoline needed to fuel the car. The gasoline we use, though processed by many humans, is a gift of nature that comes from the earth's Creator. There are parallel truths about many other experiences in contemporary life; for example, watching a movie at the theater can engage us in such a way that we feel as if we exist outside of space and time, in control of everything. However, even in such experiences, we are creatures. As such, we are dependent and vulnerable, alive on the earth in a world of space and time.

Another aspect of our being is revealed by our creatureliness: our relation to the source of our being. Since we are creatures, our existence is contingent. We depend on the environment and on other people. And the people and things upon which we depend are also creatures, so that each thing upon which we depend is also contingent. But there must be an ultimate source of existence, a being that is not a dependent creature but that is, in fact, the Creator. In this sense, our creatureliness reveals not only our dependence on the environment and on other people but also our inherent relationship to an uncreated Creator.

Created as Persons: "In our image, after our likeness..." (Gen. 1:26)

The notion that human beings are created in the image of God is perhaps the most profound aspect of Christian anthropology. In a highly compressed statement in the Genesis text, God says, "Let us make man in our image, after our likeness" (1:26). Although the human being is a creature like the other creatures physical and vulnerable, made out of dust there is something that makes human beings different from everything else in the created order.

In order to understand the richness of this revelation that human beings are created in the image and likeness of God consider the narrative of Creation from the second chapter. In contrast to the first chapter, which gives an almost objective sense of the truth about the human person that we are created in God's image and likeness the Yahwist narrative explores the subjectivity of human consciousness in a manner that complements the more objective structure of Genesis 1:26-31. In the simplicity of the Yahwist narrative, we are told that the Lord God forms man from dust and then breathes the breath of life into his nostrils, "and man became a living being" (2:7). The breath of life, though invisible to the eye, reveals the spiritual character of human life. The spirit of God is present in every human life. This narrative action the image of God breathing life into the human being shows that the human person cannot be understood or explained completely by physical attributes. The categories of this world, which focus on observable phenomena, do not exhaust the mystery of the human being.

In the Yahwist account of chapter two, God is presented as a person, almost as if he were a human being. Not only does God breathe into Adam's nostrils, but he also speaks to Adam, instructing him that he may freely eat of any tree except one. Here God is presented as personal, and he treats Adam as a person. This becomes even clearer later in chapter two, after the prohibition against eating the forbidden fruit: "Then the Lord God said, 'It is not good that the man should be alone; I will make a helper fit for him'" (2:18). In noticing the human being's subjective feelings, God shows a personal concern for him. The human being is not treated merely as an individual member of a species but as a person.

In addressing the significance of being a person, the Yahwist text calls our attention to the problem of human solitude. Another difference between the Elohist account of Creation in chapter one and the Yahwist account in chapter two involves the treatment of gender in human relations. In chapter one, the text moves quickly from telling us that we are made in God's image and likeness to telling us "male and female he created them" (1:27). However, the narrative in chapter two calls our attention to the problem of solitude even before there seems to be any genuine awareness of the issue of gender. In English translations we sometimes miss this point because the same word, man, is used in the translation of two Hebrew words. In Genesis 2:7, where the text states that "man became a living being," the issue of gender is less present. The text could almost be translated, "the human became a living being." In contrast, later in the chapter, after the creation of the woman (2:22), the man is then identified, by another Hebrew word, as male. So when the problem of human solitude is made explicit in God's statement that "it is not good that the man should be alone" (2:18), man is used in the sense of being a human. One way of understanding the biblical text at this point is to recognize that solitude is a problem that faces every human person, male and female.

God recognizes, as humans also do, that material goods alone are not adequate to resolve the problem of solitude. In the Yahwist account, God makes animals and birds for the man, "but there was not found a helper fit for him" (2:20). In part, this verse reveals that the man, and hence every human being, has an interior life and a capacity for a subjective experience of himself as a person. While we human beings live in relation with the other creatures of the world, we also live in relation with ourselves and can be aware of ourselves. In fact, to be a human being is to be a person who is capable of self-awareness. In this sense, the narrative of the Yahwist account in chapter two helps explain, in part, the Elohist account from chapter one, which states that human beings are created in the image and likeness of God. God is a person, and, as such, he takes a personal interest in our well-being. Like God, we are persons, endowed with a capacity for self-awareness.

Because human beings are created in the image and likeness of God, we have both physical and spiritual aspects. We are always both 1) embedded in the here and now, at this place and in this time, conditioned by this particular background and with these individual propensities, desires, and talents, while also 2) able to gain a critical distance from the concrete facticity of our physical and social condition. The human being is a created person, a spiritual animal, a synthesis of the eternal and the temporal, living in the finite world of time but marked with the spirituality of infinitude. As the psalmist puts it, "What is man that thou art mindful of him, or the son of man that thou dost care for him? Yet thou hast made him little less than God, and dost crown him with glory and honor. Thou hast given him dominion over the works of thy hands; thou hast put all things under his feet" (Ps. 8:4-6).

Genesis 1:26 is rich with theological insight into the nature of the human person, but other elements from the Elohist narratives of chapter two and three provide further insight into what it means to be created in the image of God. Traditionally, this includes both human intellect and will. It is appropriate, therefore, to turn to an examination of our capacities to know the truth and to act with the power of self-determination.

Endowed with a Capacity to Know the Truth: "The man gave names to all..." (Gen. 2:21)

The Yahwist narrative of chapter two, after calling our attention to the problem of human solitude and our capacity for self-awareness, then states, "So out of the ground the Lord God formed every beast of the field and every bird of the air, and brought them to the man to see what he would call them; and whatever the man called every living creature, that was its name. The man gave names to all cattle, and to the birds of the air, and to every beast of the field" (2:19-20).

This power the ability to call things by name is a unique gift given to human beings, a sign of human intellectual ability to pursue the truth. In the Elohist account, the intellectual power of humans is indicated in the verse that states, "Let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the birds, and over the cattle, and over all the earth…." (1:26). Although we are material creatures (and are, therefore, part of the physical world, like all of the other animals on the earth), our intellectual capacity puts us in a different position relative to the rest of creation. We can use our rational capacities to gain an intellectual distance from the rest of the world. What animals can sense and perceive, we can know and understand, at least in part. Therefore, we are in a special position of stewardship. We are to guard and keep the other creatures in the natural order.

During the past several centuries, especially following Francis Bacon with the rise of modern science, some people have tended to think that the mandate, "let them have dominion," is a call to conquer the world. In this way of thinking, the human person is understood as standing outside of space and time, observing the world in order to predict and control creation. But the words of Genesis are much less severe. Dominion includes making the earth a domicile, a home. Since we, as human beings, have the capacity to gain critical distance from the objects of creation, even while remaining a part of it, we are called to be stewards of creation, using our knowledge to care for the earth.8

There is an important difference in the way that the power of language is treated in the first and second chapters of Genesis. In the first chapter, God speaks, and by his word he creates the entire material world, word by word. "And God said, 'Let the earth bring forth living creatures according to their kinds: cattle and creeping things and beasts of the earth according to their kinds.' And it was so" (1:24). In contrast, in the Yahwist account, we are told that "the Lord God formed every beast of the field and every bird of the air, and brought them to the man to see what he would call them; and whatever the man called every living creature, that was its name" (2:19). The difference between these two accounts reveals a deep insight about the power of language and the human capacity for rational thought.

The word of God is the source of all being and order in the world. This truth is made explicit in the first chapter of Genesis. God creates everything, "each according to their kinds" (1:24). God, who is depicted here as a personal God and also as the paradigm of perfect reason and truth, creates everything through the power of his word. Human beings, as persons created in God's image, are also endowed with the power of language. However, the relationship between creativity and discovery is different for humans than it is for God. God speaks creation into existence by his word. Although human beings cannot use the power of language to create material realities out of nothingness, the power of human language is, nonetheless, profound. It is not only part of what makes human beings different from other creatures but also part of what is meant in saying that human beings are created in the image of God.

In the Yahwist narrative in chapters two, three, and four, we see human language being used in several ways. Adam is given the power to create names for all of the animals indeed, for all of creation. However, this power of naming is not the power to create order in the universe. It is the power to discover the order created by God and to create order in one's subjectivity. This is one of the key aspects of being human. Humans have rational powers, including the ability to use language to discover the truth about the order in the world.

Endowed with the Power of Self-Determination with Accountability: "She took of its fruit and ate . . . and he ate" (Gen. 3:6)

With the power of language comes the ability to remember the past and imagine future possibilities. There is a significant shift in the way that the biblical characters use language in the second chapter of Genesis, compared with the third. In chapter two, human language is presented as a power that allows humans to name things according to their proper kinds. It is a power of discovery. In chapter three, Adam and Eve go on to discover that this power also affords them the ability to remember the past and imagine the future.

The story of the Fall reveals not only the human capacity for creative memory and imagination but also the power of self-determination with accountability.9 From the point of view of biblical criticism, the story of the Fall in the third chapter is in line with the Yahwist Creation narrative in the second chapter. In the middle of chapter two, we are told that "the Lord God commanded the man, saying, 'You may freely eat of every tree of the garden; but of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil you shall not eat, for in the day that you eat of it you shall die'" (2:16-17). With this prohibition, which arises with the capacity for language and rational thought in human consciousness, we see the capacity for self-determination awakened in the human being.

One of the conditions for self-determination is the experience of "being able," the sense that "I may, but I need not." With the prohibition, Adam takes on a new relationship to the fruit of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. He may eat of this tree, but he need not do so. He has the ability not only to imagine eating from the tree but also to imagine refraining from eating. In either case, his relationship with the imagined future possibility is one of freedom. He may choose to actualize one of the imagined possibilities, or he may not. So he is free to determine his relationship to the world and to himself.

The narrative continues in the third chapter with the account of the Fall. In chapter two, human consciousness is presented in a state of primal innocence. The conversation between man and God is one of joyous discovery, of naming and coming to understand the order of creation. But this concelebratory conversation changes in chapter three, which begins with a subtle serpent who uses language to twist memories and hopes. The serpent asks, "Did God say, 'You shall not eat of any tree of the garden'?" (3:1). Here the imaginative capacities of memory and hope are being subtly twisted. Eve still remembers correctly that God said they may eat from every tree but one. But the serpent twists her memories and hopes again. He tempts her to eat the forbidden fruit and adds, "You will not die" (3:4). Now she is further drawn to the possibility of violating the prohibition. She becomes more intensely attracted to the tree, but her attention turns to a more limited aspect of the tree's goodness; she sees that it is "good for food" (3:5). Until this point, all we know about this mysterious tree is that it is the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, and that humans have been prohibited from eating of it. Now, with Eve's memory of the prohibition having been distorted, she focuses on a particular aspect of the tree's goodness: its potential as a source of food and delight. But this is precisely what God prohibited when he said, "You shall not eat" of that tree (2:17).

This story shows a subtle interplay of various aspects of human consciousness. The woman's awareness vacillates between her intellect, with her knowledge of the tree, and her will, with her attraction to various aspects of goodness. Her capacity for intellectual understanding allows her to know something about the tree, while her will to love what is good is shifts between various aspects of goodness. Previously, in innocence, the man and the woman were in close conversation with God and with each other. "The man and his wife were both naked, and were not ashamed" (2:25). In the experience of temptation, a dynamic interplay emerges between the woman's intellectual awareness of the tree and the desire of her will for what is good. Her attention is subtly shifted away from the goodness of her right relationship with God, her husband, and her environment until she instead focuses on the goodness of the fruit of the tree "for food." Then, she makes a free choice to eat the forbidden fruit. In doing so, she is attracted to one aspect of the goodness of the tree that it is good for food while consciously ignoring a greater truth about her relationship to the tree, to God, and to her husband.

The text provides only a brief description of the spiritual moment of decision: "She took of its fruit and ate; and she also gave some to her husband, and he ate" (3:6). In making this free choice, the man and the woman fall from their original state of innocence into a distorted relationship with God, with each other, and with their environment. "Then, the eyes of both were opened, and they knew that they were naked; and they sewed fig leaves together and made themselves aprons" (3:7). Once again, the narrative of the Yahwist account provides a profound description of the subjectivity of human consciousness. For Adam and Eve, breaking their covenant with God also distorts their own subjectivity. In innocence, they were naked and not ashamed. But after the Fall, consciousness folds back on itself in a distorted form, causing them to see their own nakedness and feel with it a sense of shame.

In shame, the man and the woman cover themselves and hide from each other. Again, the primal simplicity of the story reveals deep insights into the nature of human consciousness:

They heard the sound of the Lord God walking in the garden in the cool of the day, and the man and his wife hid themselves from the presence of the Lord God among the trees of the garden. But the Lord God called to the man, and said to him, "Where are you?" And he said, "I heard the sound of thee in the garden, and I was afraid, because I was naked; and I hid myself." He said, "Who told you that you were naked? Have you eaten of the tree of which I commanded you not to eat?" The man said, "The woman whom thou gavest to be with me, she gave me fruit of the tree, and I ate." Then the Lord God said to the woman, "What is this that you have done?" The woman said, "The serpent beguiled me, and I ate." (3:8-14)

When the Lord God asks for an account from Adam, we see the same pattern of distorted memories through a self-deceptive interplay between the man's intellect and will. There is a sense in which the man's response to God is true: "She gave me the fruit, and I ate" (3:12). Though acknowledging his own agency, he implies that the blame should be placed on the woman. He recognizes that he is the author of his own action "I ate" yet he tries to go even further to distance himself from his own action by identifying its source either in the woman or in God. The response of the woman is similar: "The serpent beguiled me, and I ate" (3:14).

An important and difficult philosophical question is raised in this part of the story: What is the cause of human action? The story reveals three insights that are helpful in answering this question. First, human beings are endowed with the power of self-determination. When a human being makes a free choice, that action is determined by the agent doing the acting. Since a human being is a creature and, as such, always acts in a particular context, the environment and other human beings may condition the action. But insofar as the action is the result of a free choice, it is determined by the agent, not by the environment that the agent inhabits. Second, this power of free choice is not a morally neutral power, such that any choice, as long as it is made passionately, is a good choice. The man and the woman find themselves in a particular context in a covenant with God and with each other. They are instructed about what is good and what is not. And yet they each use their power of will to make a bad choice. In doing so, they break their covenant with God, wound their relationship with one another, and distort their own self-awareness, making them prone to continued self-deception in the future. The self-determined choices of both Adam and Eve have effects on the world, on their relationships with others, and on their own subjectivity. The woman eats, thereby changing the fruit by picking it, eating it, and digesting it. But this action also results in a change in her relationship with her husband and with the Lord God. She becomes aware of her nakedness and covers herself in modesty from her husband. Ashamed of herself, she hides from God. The Fall also brings about a change in her. She becomes aware of herself as a person who has disobeyed. By making a self-determined choice, she changes not just the world and her relationship with others; she changes herself. The same is also true of Adam. Adam and Eve's misuse of freedom is exacerbated by their subsequent refusal to take responsibility for their bad choices.

As the text continues, the Lord God pronounces a curse upon the serpent, the woman, and the man. This shows that each one is accountable for his or her own self-determined actions, regardless of external conditions. The Lord God gives the man and woman the freedom to make their own choices, since each human person is endowed with a capacity for self-determination. But this capacity to make self-determining choices is rightly ordered toward goodness and truth. The choices made by the man and the woman are free both in the sense that they are unencumbered by external restraints and in the sense that they are self-determined. But the choice to eat the fruit is not liberating, since it is a choice to try to become something that is contrary to one's nature. Choosing to give in to temptation places the man and woman in the bondage of guilt and shame. They make matters worse by denying responsibility, placing blame elsewhere, and hiding from themselves and from God.

Authentic freedom involves making self-determined choices ordered toward knowing the truth and loving goodness. The misuse of freedom hinders one's ability to orient oneself properly toward goodness and truth without divine assistance, but not to the degree that the power of self-determination is lost. Even after eating the forbidden fruit, the man and the woman retain their capacity for self-determination in their response to God when asked why they are hiding. God comes looking for them, but in a way that respects their freedom. And even when each shirks responsibility for his or her actions, God holds them accountable but does so in a way that continues to respect their capacity for self-determination. As a consequence of their fall into guilt, Adam and Eve are cast out from their state of Edenic bliss, but not before "the Lord God made for Adam and his wife garments of skins, and clothed them" (3:21). We are accountable for the way we use our power of self-determination, but God continues to treat us with mercy.

Conditioned by Disordered Social Structures: "What is this that you have done?" (Gen. 3:13)

There is a mysterious sense in which every human being who sins participates in the Fall. The blissful joy of the nineteen-month-old child who delights in naming everything in her world becomes, with misused freedom, the recognition in older children that moral failures need to be hidden from others, and even from oneself through the subtle tactics of self-deception. So, in one sense, we all participate in the narrative of the Fall through our own sinfulness. Yet there is another sense in which the narrative of the Fall is different from our experience. After all, not only were Adam and Eve in a state of innocence in the Garden of Eden; they were also unaffected by a social environment that included other sinful humans.

Our situation is, in some ways, more like that of Cain and Abel than like that of Adam and Eve. Considered subjectively, our lives began in Edenic innocence. But considered objectively, human beings develop in a world affected by sin. The fourth chapter of Genesis begins with Adam and Eve outside of the garden of innocence. In their fallen state, they conceive, and Eve gives birth to Cain and Abel. We are told very little about the upbringing of Cain, but we can fill in some of the details. While Adam and Eve developed language and consciousness in the Edenic garden, Cain and Abel are conditioned by a different set of environmental factors. The parents of Cain and Abel are in a fallen state. As we know from the third chapter, Adam and Eve are prone to disobedience, and both have fallen into guilt. This has affected their interior lives and their interpersonal relationships, even in ways they did not expect. For example, in disobeying in the garden, they did not foresee that their own subjectivity and interiority would affect even the way they raised their children.

We might want to conclude that the distorted social environment of the first family would cause Cain and Abel to fall into sin and guilt as well. Indeed, as the story unfolds, Cain, the firstborn son of this first human family, kills his brother. But the narrative gives no indication that his deed was caused by the social environment of his family. In fact, the source of action is Cain's relationship with God rather than with his parents. The Lord God is not pleased with Cain's sacrifice we are not told why and Cain becomes very angry. The Lord then speaks to him: "Why are you angry, and why has your countenance fallen? If you do well, will you not be accepted? And if you do not do well, sin is crouching at the door; its desire is for you, but you must master it" (4:7). Cain then faces a moment of temptation that is both similar to and different from the temptation faced by his parents. Cain is endowed with the capacity to imagine various future possibilities and to choose from among them. He is not required to kill his brother. Rather, he imagines it as a future possibility, and with this sin "crouching at the door," he chooses to act on it rather than to master the temptation.

However, Cain's situation is different from that of Adam and Eve in the garden. He has not had the advantage of developing in an environment where he is surrounded by blissful innocence. Instead, he is raised in an environment that includes the effects of his parents' sin: his mother's multiplied pain in childbirth, his father's toiling in sweat to provide bread, and the thorns and thistles of life outside Eden amid a consciousness of death. Although surrounded by a sometimes physically difficult and socially distorted environment, Cain is still endowed with the capacity to make self-determining choices. And when he chooses to misuse his freedom, it is his own action: "Cain rose up against his brother, Abel, and killed him" (4:8).

Cain's response to the misuse of his freedom is almost identical to that of his parents. "The Lord said to Cain, 'Where is Abel your brother?' He said, 'I do not know; am I my brother's keeper?'" (4:9). Like his parents, he tries to avoid personal responsibility for his action. He twists his words and memories in a subtle act of self-deception by denying that he knows where his brother is. But the response of the Lord to Cain is almost the same as the response to Adam and Eve. After Adam denies responsibility for his misdeed, the Lord turns to Eve and asks her, "What is this that you have done?" (3:13). In a similar way, the Lord asks Cain, "What have you done?" (4:10).

The story of Cain and Abel offers insight into the effects of sin on subsequent generations. The biblical teaching proclaims that God visits "the iniquities of the father upon the children to the third and the fourth generation of those who hate me" (Exod. 20:5). But the story of Cain and Abel clarifies how that happens. The sin of Adam and Eve is visited upon Cain and Abel in the sense that the children develop in an environment distorted by the social effects of sin. But that distorted social environment has a conditioning not determining effect upon the children. Cain is conditioned by his environment, but that does not cause his choice. Like his parents, Cain has an interior life and his own subjectivity. We are told that he gets "very angry" and even that "his countenance [falls]" when his offering is not pleasing to the Lord. But Cain, as a human being endowed with intellect and will, is, like every human being, faced with the temptation of sin. While Cain is undoubtedly conditioned by the distorted social structures and physical environment in which he was raised, his capacity for self-determined activity still leaves him free in relation to the temptation of sin that is "crouching at the door." And, as the Lord tells him, "you must master it" (4:7).

After Cain's misdeed, he is held accountable for his action and receives a punishment. But he protests, saying, "My punishment is greater than I can bear. Behold, thou has driven me this day away from the ground; and from thy face I shall be hidden; and I shall be a fugitive and a wanderer on the earth, and whoever finds me will slay me" (4:13-14). The Lord responds, "Not so" (4:14). Although Cain is held accountable for his misdeed, the Lord orders that others should continue to treat him as a person with intellect and will. In this way, there is a parallel between the punishment of Adam and Eve when they are sent out of the garden and the punishment of Cain. In both cases, the one who commits a misdeed is held responsible, but that person also continues to be treated as a self-conscious agent with intellect and will.

Several points can be drawn from the story of Cain and Abel with regard to the account of the human person that is presented in Genesis. First, after the Fall, human beings develop in a physical and social environment that has been distorted by the bad choices of those who preceded them. Second, the misdeeds of one generation condition the environment of subsequent generations, even in ways unexpected by those committing the original misdeeds. Third, subsequent individuals should not be held accountable for the distorted physical and social environment in which they find themselves, when that environment is a result of the bad choices of those who preceded them. Fourth, the distorted physical and social environment does not cause subsequent individuals to make bad choices. When individuals make bad choices, it is the result of self-determined actions for which they are responsible. Fifth, persons who commit misdeeds as a result of their own free choice even though those wrong actions may be conditioned by a distorted environment for which the persons are not responsible should be held accountable for their misdeeds. Sixth, any punishment should recognize that wrongdoers are still persons with self-consciousness, an interior life, intellect, and will.

So far, this analysis of self-determination has focused primarily on the misuse of human freedom. In innocence, Adam and Eve misused their power of self-determination by giving in to temptation. Then, their son Cain misused his power of self-determination by killing his brother. The human being, having misused the gift of freedom, is therefore torn between knowledge of the good and knowledge of failing to abide by it. Human experience confirms this sense of having a restless heart, drawn toward goodness but, as a result of misused freedom, disrupted from the proper relationship toward the ultimate goal. The psalmist expresses the feeling of self-alienation in his song of longing: "How long, O Lord? Wilt thou forget me forever? How long wilt thou hide thy face from me? How long must I bear pain in my soul, and have sorrow in my heart all the day?" (Ps. 13:1-2).

Despite the recognition that the misuse of freedom can result in a wounded heart and a feeling of separation from God, the biblical account does not always present human beings as misusing the power of self-determination. Instead, the power of self-determination is a great gift, for only in freedom can a person direct himself toward goodness and receive providential grace.

This authentic freedom, which is central to the biblical understanding of the human person, is not the license to do whatever one wants but, rather, the liberty to choose to act in accord with the law of God, which is written on the heart of all people. Many of the later biblical narratives focus on people who, guided by divine providence, learn to make responsible use of their freedom. The two main ways in which human beings learn to exercise their freedom are in the family and at work.

Gendered, Social Creatures: ". . . Male and female he created them" (Gen. 1:27)

The discussion of the Elohist narrative of the creation of human beings has focused so far on Genesis 1:26: "Then God said, 'Let us make man in our image, after our likeness; and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creeps upon the earth.'" In drawing out the philosophy embedded in that verse, we have seen that human beings are created in the image of God and are endowed with the power to know the truth and make self-determined choices ordered toward goodness, and to be held accountable for those choices even when their environment is distorted by disordered social structures. Although we have paused to draw out the richness of verse 26, the text flows quickly into verse 27: "So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them."

From the beginning, we are told that God created human beings "male and female." Two important insights are contained in this aspect of the revelation: Human beings are gendered, and they are also social. The companionship of males and females involves one of the primary forms of interpersonal communion. From the beginning, human nature has been social in character. We develop and actualize ourselves in communion with others, primarily through our family relationships. The biblical text clearly indicates this as it continues in the next verse: "Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth and subdue it." A pattern in the text is worth noting. In verse 26, we are told that human beings are made in God's image and that they are to have dominion over the animals of creation. Then, in verse 27, we are told again that humans are made in God's image "male and female he created them" and that we are to have dominion over the earth and its many creatures. The mandate to have dominion over the earth flows from the fact that a human being possesses both intellect and will. Verse 27 indicates that this is true of both males and females, while verse 28 indicates that together, men and women are to have families as a way of taking care of the earth.

In contemporary language, we have a responsibility to be good stewards, to guard and keep the earth, to care for the environment, and to be sensitive to the dynamic balance of ecology. The biblical account ties this concern for natural ecology to a concern for human ecology a concern to guard and keep the social institutions necessary for human flourishing. We use our intellectual capacities not only to understand the workings of nature so that we can make good choices that will protect the natural environment an environment that is good in itself and necessary for human flourishing but also to understand the workings of human persons and human development so that we can make good choices that will protect the human environment. In the biblical account, human ecology primarily involves understanding the importance of the family. With regard to the next phase of welfare reform, one concern this raises is the degree to which the two-parent family is now becoming an "endangered species."

The importance of the relationship between males and females is also captured in the Yahwist narrative. As we have already indicated, in that account, God first creates a human (traditionally understood as a male, though the Hebrew text does not accentuate the issue of gender until the Lord draws a rib from the human and creates a woman). After that, the "man" is indicated more clearly by another Hebrew word that denotes the male gender.

Recall that in the Yahwist narrative, the Lord creates a helper for the man because he realizes that the human heart is not satisfied with the material things of the earth. It is when the human person can enter into communion with another human being "male and female" that a person realizes himself by choosing to give himself completely to another. This truth is captured in the joyous expression of the man as he looks upon his new mate: "This at last is bone of my bones and flesh of my flesh" (2:23). Although there are only a few words in the man's expression, we can hear his joy at seeing the woman. He knows now that there is another person like him not only physically but also spiritually. Both the male and the female are created in the image of God. Yet the man's joy does not just derive from the excitement of recognizing someone like himself; it also stems from an awareness that this other person's body indeed, the entirety of the other person will complement his being. With her, he can enter into a kind of communion of persons, sharing with her the entirety of his being.

This gift of oneself to another is captured in verse 24: "Therefore a man leaves his father and his mother and cleaves to his wife, and they become one flesh." This is the model for marriage, in which a man and woman leave the families of their childhood to form a union. The union of man and woman is ultimately based not on shared needs but on mutual self-giving. It is, of course, true that the man has a sense of solitude before he joins his wife. He feels alone and is aware of a kind of emptiness within himself that is not satisfied by the other material beings of the world. But in joining the woman, he is not merely acting on his emptiness by seeking her to fill a void. Rather, the union of man and woman into husband and wife is based on a self-determined choice to give oneself wholly to another.

This free act a self-determined choice to give oneself to another person is among the most formative decisions in the life of a human being. By freely choosing to give one's life to another person, one is choosing both to give oneself as a gift and also to become oneself. In choosing to give oneself to another person in marriage, one chooses to become the husband or wife of one's beloved.

In this sense, marriage is a further indicator of what it means to be created in God's image. God freely chose to create the world out of love. As people created in God's image, both men and women can choose to give themselves as a gift to another; in doing so, they are creating themselves into something new. The man becomes a husband, and the woman becomes a wife. For both, it is a decision that changes the world and themselves.

This giving of oneself to another includes both a turning away from other social groups and also a turning back to the common good. As the text says, "A man leaves his father and mother" (2:24). Young lovers often turn away from other social contacts in order to be alone. But the love that turns lovers toward each other in a desire to be with the other person, to receive the gift of the other more fully, and to give the gift of oneself more completely, is also a fertile love. As the two become one flesh, the communion of love issues forth, quite often, in the miracle of co-creation. Here again, the free choice to give oneself completely to one's beloved changes the world and oneself. The world is changed with the creation of another human life, and the man and woman are changed as they become father and mother.

In the unitive act of love, we see most clearly the great good of freedom and the power of self-determination. Through a self-determined act, the man and the woman become one flesh. In the Garden of Eden, Adam and Even give themselves completely to one another: "The man and his wife were both naked, and they were not ashamed" (2:25). Of course, in distorted social structures, various tensions between consciousness and erotic desire often exist. The marital act may be and often is conditioned by a myriad of factors and, hence, is sometimes twisted in unusually creative ways. In contrast to the possible forms of disordered love, the proper place for ordered love is within the covenant of marriage. In marriage, where two lovers become one, the marital act exhibits its unique unitive and procreative significance. The power of self-determination involves a choice not only to change the world but also to change oneself. We realize who we are through the actions we choose, and we become who we are through the choices we make. For most human beings, the choices of whether and whom to marry, along with the responsibilities of being fruitful and multiplying, are among the most personally formative aspects of human life. In taking on the responsibilities of creating and rearing children, we are given a special gift that allows us to realize ourselves more fully as beings created in the image of God.

Called to Work: "Till it and keep it" (Gen. 2:15)

The theme of work is addressed in each of the first four chapters of the book of Genesis. In chapter one, "God said to [Adam and Eve], be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth and subdue it" (1:28). The notion that we are to subdue the earth shows the importance of labor in human life. After all, the entire Elohist narrative of the first chapter tells the story of Creation, where God is presented as working: "On the seventh day God finished his work which he had done, and he rested on the seventh day from all his work which he had done" (2:2).

Since human beings are created in the image of God, and since God works, it follows that part of the meaning of human existence is realized in work. Thus, when Genesis states that humans are to subdue the earth, it indicates that work is an activity that human beings are to carry out in the world. Human beings are created in the image of God, and this likeness is revealed partly through the mandate to subdue the earth that is, to be like God in extending his work.10

In the Yahwist narrative of Creation, this mandate to work is even more explicit: "The Lord God took the man and put him in the Garden of Eden to till it and keep it" (2:15). Here, work is presented as a good activity. There is no indication that Adam conceives of work as a burden, or that God is using him as an object to do his work. In fact, work is presented as a good activity that involves human freedom. By analogy, God freely works: "The Lord God planted a garden in Eden, in the east; and there he put the man whom he had formed. And out of the ground the Lord God made to grow every tree that is pleasant to the sight and good for food" (2:8-9). Human work is, then, a kind of cooperation with the work of God. This is most obvious in the area of agriculture, because the work of planting and harvesting is always a cooperation with the patterns of nature that have their source in God. Likewise, every kind of work involves, to some extent, human cooperation with the work of God's creation. So work is presented as something good, an activity of God that humans are graced to share. The text gives another indication that work is a free activity, for we are told that God puts the man in the garden to "till it and keep it," just as God tells man that he is free to eat of every tree save one. There is a connection, then, between the free decision to work and the freedom to eat from the product of one's labor.

Before the Fall, work is presented as a liberating activity. By tilling and keeping the garden, man develops in his freedom so that he is free to eat. Work becomes more complicated, however, after the Fall, especially in that it is strongly associated with burdens and pain. After the Fall, God tells Eve, "I will greatly multiply your pain in childbearing; in pain you shall bring forth children" (3:16). We say that a pregnant woman ready to give birth is "in labor," thereby identifying labor with pain. Likewise, God says to Adam, "Cursed is the ground because of you; in toil you shall eat of it all the days of your life; thorns and thistles it shall bring forth to you; and you shall eat the plants of the field. In the sweat of your face you shall eat bread until you return to the ground" (2:17-19). As a result of the misuse of freedom, all labor now contains an element of toil.

Human experience confirms these truths. In innocence, young children are often drawn to work, wanting to cooperate with their elders in performing small household chores, such as putting away the dishes and vacuuming. But after a fall from innocence, the childhood joy of cooperating in work becomes the recognition that every kind of work involves an element of toil and sweat. Not only do agricultural workers have to bear thorns and thistles, but so do those who toil in factories, in construction work, in transportation, and in the service sector. Toil is also familiar to those who work in healthcare, to those who work in teaching and research, to those who run their own businesses, to those who make decisions that will have a great impact on others, to those who care for young children and the elderly, to those who are fathers and mothers indeed, to everyone.

Even though every kind of work contains an element of toil or, perhaps, because of it work is vital for human dignity. We image God more completely through work. This point is indicated subtly in the story of Cain and Abel. We are told that "Abel was a keeper of sheep, and Cain a tiller of the ground" (4:2). Notice that we are not simply told that Abel performed the activities of keeping sheep, or that Cain performed the activities of tilling the ground. Work is transitive. The work of tilling the ground brings about a change that is both objective and subjective in character. Tilling the ground changes the earth so that the dirt is better prepared to receive the seeds that will be planted. But the transitive character of work is such that the action passes over to and takes effect on both the earth and the worker. In the activity of work, not only is the earth changed; Cain is changed. Cain becomes a tiller of the ground.

In the activity of work, the human being responds to his or her call to become a person created in the image of God and to subdue the earth. The activity of work is personal an activity done by a person, a subject with an interior life who is endowed with the capacity for self-awareness, intellect, and will. Work involves making choices and acting in a planned, rational manner. Work is also an activity that forms a person. Since we realize ourselves through the choices that we make, and since work is one of the most common of our activities, work serves not only to change the world but also to change us in our quest for self-realization.

Unfortunately, work is often evaluated solely from a worldly perspective, using the standards of measurable observation. However, this way of evaluating work considering labor only in its objective sense and solely according to the standards of the world is incomplete. Considered in this way, work often comes to be separated from the person doing the work. From the point of view of the employee, labor is then viewed as an inconvenience, something to be avoided. From the point of view of the employer, work is viewed as an item of cost in the production process. However, this philosophy of work, although perhaps prevalent in the attitudes of contemporary workers and employers, represents an incomplete understanding of the authentic meaning of work. Instead of viewing humans as objects who are "for work," the deeper truth is that all work is "for humans."

Work serves several purposes. Labor is a way to improve both the world and oneself. Work changes the world by transforming it and making it more valuable. In this process, the worker is also transformed in the process of self-realization. For his labor, the individual receives benefits, typically in the form of a wage, in order to live a more satisfying life.

Work is also a condition that makes it possible to form a family, for the family requires a means of subsistence in order to develop and flourish. Further, the family is a kind of "school of work." In the family, the members develop the habits of work, learning to "till and keep" the home.

In the broader society, work is a means by which all human beings can offer their gifts and talents to others in a manner that promotes the common good. A person's work is interrelated with the work of others. Sometimes, work involves employing one's own creativity to devise better ways to meet the world's needs. At other times, it involves working with and for others in a way that more profoundly recognizes the productive potentialities of the earth as well as the needs of those for whom the work is done. Work that looks to the broader society sometimes involves foreseeing the needs of others and developing efforts to plan, produce, and deliver goods and services that satisfy the needs of others. Work entails joining with others to take initiative and risks in a disciplined way. This entrepreneurial ability draws the individual person beyond himself and his family to work with and for others in the broader society, including those persons living across the globe.

With Inherent Dignity: "Behold, it was very good" (Gen. 1:31)

Included in the Elohist account of Creation is a narrative pattern that begins on the third day of Creation where, after the work of each new day, the text states, "And God saw that it was good" (1:10, 18, 21, 25). After the sixth day, however, the pattern changes slightly. After the creation of humans, the text states, "God saw everything that he had made, and behold, it was very good" (1:31). After the creation of human beings, who are the summit of God's creation, we are told that God's creation is "very good." This statement embodies a truth that is repeated throughout the biblical tradition: Every human life has inherent dignity and worth. In the biblical account, everything that is created is good; this is especially true of human beings.

This same insight that every human life has inherent dignity and worth can be expressed and defended in both theological and philosophical terms. From a Christian theological perspective, the mysteries of the Incarnation and the Resurrection make the same point. That God entered history in the person of Jesus that he was willing to suffer death on a cross in order to take on the sins of humankind so that through his death and resurrection they would be forgiven reveals the depth of the truth that every human life has inherent dignity and worth. It is because human life is inherently valuable that, despite human sinfulness, Jesus entered history.

Apart from this and other theological perspectives, the dignity of the human person can be understood from a philosophical point of view. In the American Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson wrote, "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness." Eighteenth-century German philosopher Immanuel Kant developed a detailed argument using practical reason to show that every human being is entitled to fundamental respect. In a similar way, the insight that human beings form themselves through the choices of life reveals that every person is unique and unrepeatable.

It is beyond the scope of this chapter to develop detailed theological or philosophical arguments to defend the claim that every human life has inherent dignity and worth. However, it is worth recognizing that this claim transcends the Genesis narrative. Indeed, it has strong support throughout the biblical tradition, including the writings of the New Testament. It also resonates strongly with a deep moral intuition held by most people. And various philosophical arguments have been used to support the notion of personal dignity, including the Declaration of Independence's appeal to self-evidence. To this emphasis on human dignity the biblical tradition adds the recognition that the source of this dignity lies in the kind of beings that we are: persons created in the image of God.

Seven Themes Relating Christian Anthropology to the Next Phase of Welfare Reform

The previous section contained a detailed examination of the first four chapters of Genesis, focusing on the understanding of the human person in the biblical tradition. Broadly speaking, this account can be called a "Christian anthropology," even though many elements in this account will be shared by people from other religious traditions, and some elements will be shared even by people who are not religious. To summarize and restate this Christian anthropology: Human beings are persons created in the image of God who are gendered, social creatures with inherent dignity and endowed with the capacity to know the truth and love goodness while making self-determining choices with accountability that shape their personalities, especially through their families and labor, even while being conditioned by disordered social structures.

A Humane Vision for Thinking about the Poor

Currently, there are two dominant tendencies in the ways that many Americans think about the poor. On the one hand, there is a tendency, common on the political Left, to think that poverty causes a series of negative pathologies, and that these behaviors are not the responsibility of the acting person. This line of thinking, which can be traced back to eighteenth-century French thinker Jean-Jacques Rousseau, tends to view human beings, especially the poor, as victims of a disordered social structure. In this view, since modern society tends to divide humans into the rich and the poor, and since the poor become victims of social corruption that is completely beyond their control, they are considered victims of ill fortune. At first glance, this seems to show a deep compassion for the plight of the poor. However, implicit in this philosophy is a denial of the personhood of those who are poor, because they are viewed as mere objects affected by external forces and lacking all capacity to make genuinely free choices. This denial of a person's ability to make self-determining choices leaves this account with a false notion of compassion.

On the other hand, there is a tendency, common on the political Right, to think that poverty is entirely the responsibility of the individual. This line of thinking, which is often a reaction against the tendency of those on the political Left to disregard any accountability by those who are poor, often goes too far by placing all of the blame on the individual. But in placing all of the emphasis on the individual's responsibility for his or her plight while ignoring circumstances beyond the control of the individual, this way of thinking lacks compassion.

The understanding of the human being that is outlined above avoids both of these extremes while recognizing an element of truth in each. Since human beings are conditioned by distorted social structures, there is an aspect of truth in the view, held by those on the Left, that compassion for the poor acknowledges that poor moral choices are influenced by distorted social environments. But it is improper to see particular distorted social structures as entirely responsible for the bad choices made by the poor. Since every human being is a person, each individual remains responsible, to some extent, for his or her own individual choices. This is not a sign of human weakness; rather, it is an indication of human dignity.

Correspondingly, there is an aspect of truth in the view, held by those on the Right, that compassion requires holding the poor accountable for their own choices. However, the insight that human beings are accountable for their own choices does not mean that all of the ills of poverty are the responsibility of those who suffer its effects. Two points should be made here. First, human beings are born into social structures with varying degrees of distortion and corruption, for which they are not responsible. A distorted social nexus can have a significant conditioning influence on a person's choices. Therefore, it is inappropriate to hold individuals responsible for the social nexus into which they are born, when they have no responsibility for their environment. Second, all human beings who fall into sinfulness are responsible for their own bad choices. Although the poor are certainly not the only people who make bad choices, nevertheless, in a distorted social environment, some people can make bad choices without suffering the effects of their own moral failures. (It is often easier for people of means to avoid the harm flowing from their own bad choices than it is for poor people.) All human beings are certainly accountable for their own moral failures, but, given the world in which we live, it is possible for some people to evade responsibility for their moral failures while other people suffer unduly for the moral failures of others.

From this, we can say that Christian anthropology offers a humane vision for thinking about the poor. All human beings, including those who are poor, oppressed, or disadvantaged, have inherent dignity. Further, all human beings are conditioned by the disordered social structures into which they are born. Because poor people are often conditioned by severely disordered social environments for which they may not be individually responsible, it is appropriate to have special compassion for their plight. However, this compassion does not view the poor merely as victims; rather, it views them as persons endowed with a capacity to pursue the truth and to make self-determining choices ordered toward goodness.

Emphasis on the Importance of Marriage and Family Bonds

The Christian anthropology outlined above understands human beings as persons who are gendered and social. Humans grow and develop in families. This understanding of the human person should be used to evaluate reforms of the American welfare system. For example, policymakers should determine whether particular programs promote or weaken the institution of marriage and the family. The bonds of human belonging, especially as developed in the family, are crucial to the development of responsible freedom. Programs that provide food, clothing, and shelter without showing a concern for the personal situation of those in need may, in the long run, do more harm than good.