Forgotten Treasures: The Counterrevolutionary Lion

- PETER A. KWASNIEWSKI

Prior to the pontificate of Leo XIII, the Catholic Church in the nineteenth century was under siege and on the defensive.

|

|

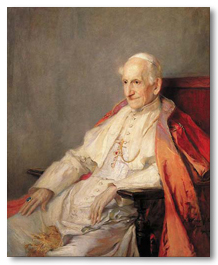

Pope Leo XIII

(1810-1903) |

In many ways she was marginalized and held in contempt; the enlightened liberals who ran the show in Europe (as they do today) belittled her medieval words and ways and predicted her disappearance as a matter of course. Her supreme leader was left little choice, it seemed, but to hurl protests and anathemas at a heedless world.

Secularists would simply not have thought it possible that the Church would rally and boldly respond to the challenges of the day, gaining the moral high ground where she had lost physical territory or political support. Yet this is precisely what happened thanks to the surprising pontificate of Gioacchino Vincenzo Raffaele Luigi Pecci, better known as Pope Leo XIII, who reigned from 1878 to 1903 (25 1/2 years), a pontificate exceeded only by those of Bl. Pius IX (almost 31 1/2 years) and John Paul II (26 1/2 years).

Due to the immense importance of Leo XIIIs writings, I feel fully justified in giving him two articles in this ongoing series. In the present article I will consider his forceful and incomparable social encyclicals, while in the next I will speak of several encyclicals he wrote on other subjects.

Pope Leo XIIIs landmark interventions on political and economic issues created, in essence, a new category of papal writing, one that went far beyond particular regional issues or temporary problems to become the vehicle of an entire social ethics, a body of social doctrine. That this Pope was aware from the very start of his God-given mission to articulate such a doctrine is beyond question. Confronted by the tangled state of affairs between the Church and secular regimes, the new Pope sized up the magnitude of the task that lay before him and began to take action. His inaugural encyclical Inscrutabili Dei Consilio (1878) already sounds many major themes that will occupy him for the next quarter century.

A Crash Course in Catholic Social Teaching

Considering that this Pope wrote nearly 100 encyclicals addressing a wide variety of subjects and audiences (though most of them were very brief, often no more than a few pages), it may seem a daunting task to recommend a modest number of must-reads. Fortunately, it is not difficult to do, because Leo XIII himself told us near the end of his pontificate, in the retrospective letter Annum Ingressi Sumus (1902), which of the social encyclicals he considered the most important. Vatican posterity stands in agreement with his judgment, as demonstrated by citations found in subsequent magisterial documents.

There are five encyclicals that, taken together, make up a veritable crash course in the fundamentals of Catholic social teaching: Diuturnum Illud (1881), on the origin of civil authority; Immortale Dei (1885), on the Christian constitution of States; Libertas Praestantissimum (1888), on true and false freedom; Sapientiae Christianae (1890), on the duties of Christian citizens toward their States; and Rerum Novarum (1891), on labor and capital (i.e., the rights and duties of owners and workers).

To these precious and unsurpassed repositories of Catholic teaching on the subject matters treated might be added two other highly illuminating documents: Humanum Genus (1884) on the scourge of Freemasonry and Au Milieu des Sollicitudes (1892) on Church and State in France. Nothing could be more valuable than to study these seven documents in their entirety as an introductory course in Catholic social thought.

Election-Year Reading

First, there is Diuturnum Illud, in which Leo XIII demonstrates why God is and must be the source of all political societies as well as of any authority their rulers wield. Notably, the people who may have elected the rulers are not the source of their powers, nor are those rulers beholden to the people so much as they are to Almighty God, who will judge them all the more severely for the weight of their responsibility.

Correcting numerous Enlightenment-derived errors that American Catholics typically make about the origin and purpose of political power, this encyclical makes for especially eye-opening reading in an election year. We find here too an excellent account of what is called civil disobedience but is, in reality, consistent obedience to Gods higher law.

God and the State

Second on the list is Immortale Dei, in which Leo XIII unfolds in some detail the ideal Christian constitution of a state and why it is impossible to maintain that states have no obligations to God or the Church and no obligation to form their citizens in moral virtue. As before, Leo argues vigorously against the principles and foundation of a new conception of law he has in mind the Enlightenment theory of the social contract that contradicts both the divine law and the natural law, and so undermines the stability of the State, which depends on the successful profession of religion within it, the fulfillment of each citizens sacrosanct duty to God.

This encyclical also contains one of the best accounts ever penned of the likenesses and differences between civil or secular society and the society that is the Catholic Church; it depicts with exceptional clarity their proper spheres of authority, as well as how they may overlap or come into conflict.

The Meaning of Human Freedom

Closely connected to the foregoing is Libertas Praestantissimum, which remains the most comprehensive and acute analysis of the meaning of human freedom that has yet come to us from the Chair of St. Peter. This surely explains why it has also been among the most often mentioned and cited documents in the writings of all of Leos successors in the papacy.

It would be impossible to exaggerate the value or the depth of this encyclical, which speaks of the human wills dependency on law, truth, and grace; how freedom when abused leads to slavery; how the eternal law, the natural law, and human law are interconnected; how modern political liberalism (meaning the doctrine of eighteenth-century philosophers like John Locke) opens a way to universal corruption; why the total separation of Church and State is a manifest absurdity, and yet why toleration of false religions may be permissible when greater evils can be averted thereby. It would be hard to imagine topics weightier or more perennial than these.

Christian Citizens in Modern Societies

Inserting yet another key component, Leo XIII issued Sapientiae Christianae on the rights and responsibilities of Christians as citizens in modern societies. As we might have expected, the Pope speaks with wisdom and prudence about a host of questions that face the Catholic citizen: What is true patriotism or national piety, and how is it related to devotion to the Church? What is the mission of the laity and the Catholic family in the secular world, what are the rules that must govern a Catholics political choices, and what kind of behavior of Christians in the public sphere is base and insulting to God? How are Church and State meant by divine Providence to work together such that citizens may achieve natural and supernatural perfection?

In passing, Pope Leo takes up a number of other questions, such as what a laymans attitude should be toward erring bishops and why Christians who fail to live out their faith are guilty of a sin worse than that of the Jewish people in rejecting their Messiah. Leo XIII spells out, with greater clarity than proponents of civil rights were able to do later on, the whys and wherefores of following ones conscience over against a governments immoral dictates.

Rerum Novarum

Just mention the encyclical Rerum Novarum in some circles and you will invite a torrent of words of appreciation from Catholics attuned to social doctrine, or, if you are less fortunately surrounded, a torrent of criticism from those wedded to liberal capitalism or Marxist-flavored socialism. Regrettably, many people have approached this encyclical as if they would find in it a comprehensive summary of Catholic social doctrine something it surely neither contains nor ever sets out to offer.

Pope Leo took pains to note in the document itself that he had written other encyclicals that must be read in order to supply the proper context for its predominantly economic considerations. These considerations include why socialism is emphatically unjust and guaranteed to make things worse rather than better; how the institution of private property, or possession of ones own goods, functions favorably for individual, family, and State; how the family is, in some sense, prior to the State, and yet why the States role in promoting the common good of a larger group is most useful and necessary; why the State must protect and enforce the rights and duties of various classes.

The employers duties as well as the workers are clearly spelled out; the chief and most excellent rule for the right use of money is laid down (doesnt that alone whet your appetite to read this document?); the influential concept of the just wage and the family wage are defined and defended against objections; and workingmens unions or guilds, along with the right of association, are strenuously defended. I am always amazed when I go back to this encyclical to see just how the mighty economic struggles and sufferings of the twentieth century (and indeed of our new century) are anticipated therein, their causes exhibited, their solutions proposed.

Catholics and Freemasons

The very fact that the Church, under the signature of then-Cardinal Ratzinger, reiterated as recently as 1983 that Catholics are forbidden to join Masonic associations under pain of excommunication should give us pause: What are Freemasons secretly hoping and striving to accomplish? Pope Leo XIII answers this in his powerful encyclical Humanum Genus, which, as you might have guessed, was instantly branded inaccurate, bigoted, and fantastical by the Freemasons themselves. In it, Leo soberly exposes the goals and methods of the Freemasons, defines their fundamental doctrine (naturalism), and predicts, with a prophetic voice comparable to Paul VIs in Humanae Vitae, the eventual effects of that naturalism once it has been embraced and made the foundation of States, as indeed has occurred throughout the modern Western world.

Take Up Your Cross and Vote

My last recommendation is somewhat unusual, in that Au Milieu des Sollicitudes is an encyclical addressed not to all the bishops of the world, as are the others mentioned above, but rather to the French episcopacy in particular, struggling as they were with a divided flock unable to agree on whether to lend support to a secular democracy or hold out for the restoration of Catholic monarchy.

Having thrust himself into this dispute, Pope Leo explains why Catholics should be prepared to mobilize their support even for governments or political systems that manifestly fall short of the ideal, and draws a crucial distinction between constituted power and legislation, or roughly, between the constitution as such, which may be imperfect and even anti-Christian, and the actual legislation that goes on, which may be quite good if there happen to be good men elected to office by organized Catholics.

The Pope basically says: Better good laws under a secularist government than rotten laws under an optimal type of government. While, in the end, Pope Leo was not able to convince many French Catholics that they should take up their cross and vote, he nevertheless offers to us, here and now, insightful guidance in our dark and ever-darker period of history, when scarcely any government has either a Catholic constitution or any intention of showing special friendliness to the Church.

Taking the Lead: Engaging the Modern World

In the pontificate of Leo XIII we find ourselves face to face with something truly remarkable: a systematic and subtle plan for engaging the modern world a plan that he pursued energetically and without deviation for a quarter of a century. He was gifted with an uncanny ability to speak the full truth forcefully yet phrase it diplomatically; he succeeded both in rallying the Catholic world and easing tensions with many secular powers.

While Pope Leo was deeply critical and pessimistic about the direction the Western world was going in and knew that its secular philosophies were mortal poison, what animated him above all was an intensely positive vision of what Christ and Christ alone can do for modern men, who desperately need salvation from the idols fashioned by their own hands. This is one obvious way in which Pope Leos social encyclicals remain vitally relevant and important to us, here and now.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Peter Kwasniewski. "Forgotten Treasures: The Counterrevolutionary Lion." Lay Witness (January/February, 2008).

Reprinted with permission of Lay Witness.

Lay Witness is the flagship publication of Catholics United for the Faith. Featuring articles written by leaders in the Catholic Church, each issue of Lay Witness keeps you informed on current events in the Church, the Holy Father's intentions for the month, and provides formation through biblical and catechetical articles with real-life applications for everyday Catholics.

The Author

Peter Kwasniewski holds a B.A. in Liberal Arts from Thomas Aquinas College and an M.A. and Ph.D. in Philosophy from The Catholic University of America. After teaching at the International Theological Institute in Austria and for the Franciscan University of Steubenville’s Austrian Program, he joined the founding team of Wyoming Catholic College in Lander, Wyoming, where he taught theology, philosophy, music, and art history, and directed the choir and schola. He is now a full-time author, speaker, editor, publisher, and composer. Among his books are Resurgent in the Midst of Crisis: Sacred Liturgy, the Traditional Latin Mass, and Renewal in the Church, A Missal for Young Catholics, and Noble Beauty, Transcendent Holiness: Why the Modern Age Needs the Mass of Ages. His website is here.

Peter Kwasniewski holds a B.A. in Liberal Arts from Thomas Aquinas College and an M.A. and Ph.D. in Philosophy from The Catholic University of America. After teaching at the International Theological Institute in Austria and for the Franciscan University of Steubenville’s Austrian Program, he joined the founding team of Wyoming Catholic College in Lander, Wyoming, where he taught theology, philosophy, music, and art history, and directed the choir and schola. He is now a full-time author, speaker, editor, publisher, and composer. Among his books are Resurgent in the Midst of Crisis: Sacred Liturgy, the Traditional Latin Mass, and Renewal in the Church, A Missal for Young Catholics, and Noble Beauty, Transcendent Holiness: Why the Modern Age Needs the Mass of Ages. His website is here.