Hannah Arendt, totalitarianism, and the distinction between fact and fiction

- BISHOP ROBERT BARRON

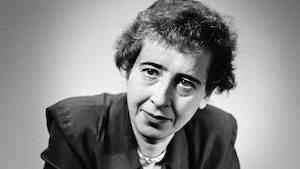

Hannah Arendt worried about the blurring of distinctions between the real and the unreal, between truth and falsity.

I am currently making my way through D.C. Schindler's marvelous book The Politics of the Real: The Church Between Liberalism and Integralism. This text will be of interest to anyone passionate about the vexed and much-discussed issue of the relation between religion and politics. But I would like to draw particular attention to the epigram that Schindler chose for his book, an observation that is meant to haunt the minds of his readers as they consider his particular arguments.

I am currently making my way through D.C. Schindler's marvelous book The Politics of the Real: The Church Between Liberalism and Integralism. This text will be of interest to anyone passionate about the vexed and much-discussed issue of the relation between religion and politics. But I would like to draw particular attention to the epigram that Schindler chose for his book, an observation that is meant to haunt the minds of his readers as they consider his particular arguments.

It is drawn from the writings of Hannah Arendt, the twentieth-century German-Jewish scholar most famous for her lucubrations on the phenomenon of totalitarianism, and it is of remarkable relevance to our present cultural conversation. She said: "The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction (i.e., the reality of experience) and the distinction between the true and the false (i.e., the standards of thought) no longer exist."

We might define totalitarianism as the controlling of every aspect of life by the arbitrary will of a powerful individual or group. If this is accurate, we see why Arendt worried about the blurring of distinctions between the real and the unreal, between truth and falsity. The objectively good and the objectively true have their own intrinsic authority — that is to say, they command, by their very excellence, the obedience of the receptive mind and the responsive will. So, for example, in the presence of mathematical truths, scientific data, and philosophical arguments, the mind surrenders, and rejoices in its surrender. It does not arbitrarily impose itself on things as with totalitarianism; rather, the intrinsic truth of things imposes itself on the mind and thereby awakens it to its purpose. In the language of Thomas Aquinas, the intelligibility of the world actualizes the mind.

In a similar way, the intrinsic goodness of things engages, excites, and actualizes the will. Aquinas said that the will is simply the appetitive dimension of the intellect, by which he meant that the good, understood as such, is automatically desired. The point is that, once again, the subjective faculty does not impose itself on reality, making good whatever it wants to be good; rather, on the contrary, what is densely and objectively good commands the will by its own authority. And as I have argued often before, this acquiescence of the will is not a negation of freedom but the discovery of authentic freedom: the same St. Paul who said that he was a slave of Christ Jesus also said that it was for freedom that Christ had set him free. That apparent contradiction is in fact the paradox produced by the fact that the will is most itself when it accepts the authority of the objective good.

Now, does anyone doubt that we are living in a society that puts such stress on the feelings and desires of individuals that it effectively undermines any claim to objectivity in regard to truth and goodness? Does anyone doubt that the default position of many in our culture is that we are allowed to determine what is true and good for us? Some years ago, as part of a social experiment, a five-foot, nine-inch white man went on a university campus and randomly asked students passing by whether they would consider him a woman if he said he felt he was a woman. A number of students said they were okay with that. Then he inquired whether they would accept that he was a Chinese woman, if that's what he claimed to be.

One student answered: "If you identified as Chinese, I might be a little surprised, but I would say good for you — be who you are." Finally, he wondered whether they would agree that he was a six-foot-five Chinese woman. This last suggestion seemed to throw his interlocutors a bit. But one young man answered: "If you . . . explained why you felt you were six-foot-five, I feel like I would be very open to saying you were six-foot-five, or Chinese, or a woman." Do you recall the Academy Award–winning film The Shape of Water, in which a woman falls in love with an aquatic creature? The title of that movie gives away the game: a dispiriting number of people in our culture feel that the only shape is the shape of water — which is to say, no shape at all, except the one that we choose to provide.

What opens the door to totalitarianism is, she thought, the radical indifference to objective truth, for once objective value has been relativized or set aside entirely, then all that remain are wills competing for dominance.

With all of this in mind, let us return to Hannah Arendt. What opens the door to totalitarianism is, she thought, the radical indifference to objective truth, for once objective value has been relativized or set aside entirely, then all that remain are wills competing for dominance. And since the war of all against all is intolerable in the long run, the strongest will shall eventually emerge — and inevitably impose itself on the other wills. In a word, totalitarianism will hold sway. Notice, please, that one of the features of all totalitarian systems is strict censorship, for an authoritarian regime has to repress any attempt at real argument — which is to say, an appeal to an objective truth that might run counter to what the regime is proposing. The great Václav Havel was the first president of the Czech Republic after the break-up of the Soviet bloc and a famously dissenting poet who had been imprisoned for his positions against Communism. He commented that, through his writings, he had opened up a "space for truth." Once that clearing was made, he said, others commenced to stand in it, which made the space bigger, and then more could join. This process continued until so many were in the space for truth that the regime, predicated upon the denial of truth, collapsed of its own weight.

I do believe that we are in a parlous condition today. The grossly exaggerated valuation of private feelings and the concomitant denial of objective truth and moral value have introduced the relentless war of wills — and evidence of this is on display in practically every aspect of our culture. Unless some of us open up a space for truth and boldly stand in it, despite fierce opposition, we are poised to succumb to the totalitarianism that Hannah Arendt so feared.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Bishop Robert Barron. "Hannah Arendt, totalitarianism, and the distinction between fact and fiction." Word on Fire (August 10, 2021).

Bishop Robert Barron. "Hannah Arendt, totalitarianism, and the distinction between fact and fiction." Word on Fire (August 10, 2021).

Reprinted with permission of Bishop Robert Barron.

The Author

Bishop Robert Barron is the founder of Word on Fire Catholic Ministries and bishop of the Diocese of Winona-Rochester in Minnesota. He is also the host of CATHOLICISM, a groundbreaking, award-winning documentary about the Catholic Faith, which aired on PBS. Bishop Barron is a #1 Amazon bestselling author and has published numerous books, essays, and articles on theology and the spiritual life. He is a religion correspondent for NBC and has also appeared on FOX News, CNN, and EWTN. Bishop Barron's website, WordOnFire.org, reaches millions of people each year, and he is one of the most-followed Catholics on social media. His regular YouTube videos have been viewed over 150 million times. Bishop Barron's pioneering work in evangelizing through the new media led Francis Cardinal George to describe him as "one of the Church's best messengers." He has keynoted many conferences and events all over the world, including the 2016 World Youth Day in Kraków, Poland, as well as the 2015 World Meeting of Families in Philadelphia, which marked Pope Francis' historic visit to the United States. He is author of Exploring Catholic Theology, And Now I See: A Theology of Transformation, Thomas Aquinas: Spiritual Master, Heaven in Stone and Glass: Experiencing the Spirituality of the Great Cathedrals, Eucharist (Catholic Spirituality for Adults), The Priority of Christ: Toward a Postliberal Catholicism, and Word on Fire: Proclaiming the Power of Christ.

Bishop Robert Barron is the founder of Word on Fire Catholic Ministries and bishop of the Diocese of Winona-Rochester in Minnesota. He is also the host of CATHOLICISM, a groundbreaking, award-winning documentary about the Catholic Faith, which aired on PBS. Bishop Barron is a #1 Amazon bestselling author and has published numerous books, essays, and articles on theology and the spiritual life. He is a religion correspondent for NBC and has also appeared on FOX News, CNN, and EWTN. Bishop Barron's website, WordOnFire.org, reaches millions of people each year, and he is one of the most-followed Catholics on social media. His regular YouTube videos have been viewed over 150 million times. Bishop Barron's pioneering work in evangelizing through the new media led Francis Cardinal George to describe him as "one of the Church's best messengers." He has keynoted many conferences and events all over the world, including the 2016 World Youth Day in Kraków, Poland, as well as the 2015 World Meeting of Families in Philadelphia, which marked Pope Francis' historic visit to the United States. He is author of Exploring Catholic Theology, And Now I See: A Theology of Transformation, Thomas Aquinas: Spiritual Master, Heaven in Stone and Glass: Experiencing the Spirituality of the Great Cathedrals, Eucharist (Catholic Spirituality for Adults), The Priority of Christ: Toward a Postliberal Catholicism, and Word on Fire: Proclaiming the Power of Christ.