Concupiscence in the West-Schindler Debate

- DAVID DELANEY & JANET E. SMITH

The ongoing Theology of the Body debate between Christopher West and his critics is an important one.

|

An Important Debate

The ongoing Theology of the Body debate between Christopher West and his critics (including Alice Von Hildebrand, David Schindler and Dawn Eden) is an important one. For those not familiar with it, I suggest reading David Schindler's initial open letter, Christopher West's public response and Dawn Eden's thesis. West's public response correctly identifies the primary issue; concupiscence. It, at least in part, underlies most of his critic's concerns.

Concupiscence vs. Mature Purity

Schindler claims that West's understanding of concupiscence is deficient because he neglects to understand "that concupiscence dwells 'objectively' in the body, and continues its 'objective' presence in the body throughout the course of our infralapsarian existence." Eden explicitly quotes Schindler citing the same concern.

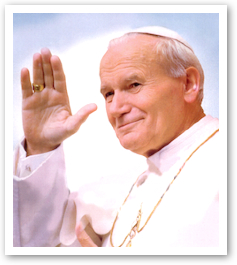

West admits he may have under emphasized the "fierce" and enduring nature of concupiscence in the past. Nevertheless, he doesn't retreat from his emphasis that redemption brings about liberation from concupiscence, and for good reason. The words come from JPII. West points to 15 references in the TOB catecheses in support of this. Accordingly, one of West's central themes is "mature purity."

West believes mature purity excludes continence. Rather than turning away from temptations, it is an achievement in which one no longer need turn away. This view has singularly important implications. West's application of this theory is best illustrated by his recourse to the story of two bishops encountering a scantily clad prostitute. One turns away, the other looks carefully. The bishop who continues his gaze has achieved mature purity and should be everyone's model.

Before considering West's view, we must make an important clarification about Schindler's terminology about concupiscence's objectivity. Concupiscence is an objective state but it is not a created reality, because only God creates. The nature of concupiscence is that of all evil; it deprives a good of something necessary (see TOB 27:2). Concupiscence is parasitic upon some created good. West legitimately rejects Schindler's criticism to the degree he understands him to be making this mistake.

West correctly interprets John Paul II's demand that we can and must cooperate with grace in order to overcome concupiscent temptations. We have to demand self-mastery from ourselves in each and every temptation, explicitly demanding we orient our will toward the authentic good. For example, when tempted to reduce a woman to her sexual value because he notices the shape of her body, a man must demand of himself that he see and affirm her as created by God for her own sake. He must endeavor to recover the habitually threatened spousal meaning of the body (TOB 32:3). West rightly emphasizes this point.

Christopher West rightly teaches John Paul's articulation of the good news for the man of concupiscence. He can liberate himself from the constraint of concupiscence though not its continual draw. But he is wrong to suggest one may reach a point at which he need not exercise continence. |

In general, West is correct about that which John Paul explicitly teaches in this regard. However, I think that he seriously errs when he leaves JPII's explicit words to concretely apply TOB. In the case of mature purity, West makes important observations about its significance. For example, he cites St Thomas Aquinas' Summa theologiae (I-II, q. 58, a. 3, ad. 2) showing continence is not a virtue because by itself it doesn't subordinate the sensitive appetites to the rational faculties. But West uses this to justify his claim that we must reach a state in which we no longer resort to continence.

Here West goes beyond what JPII actually says. It is true that John Paul follows St. Thomas's categorization of concupiscence, but that it comes from St. Thomas ought to give West pause. This definition comes from Aristotle and so necessarily does not take into consideration the effects of concupiscence. Thomas does and so he clarifies that in the narrow sense continence is not a virtue, but in a broader sense it is (see ST II-II, q. 155, a. 1). Not surprisingly, John Paul II also calls continence a virtue (TOB 124:4). This is important because holding too strongly to the precise definition seems to have misled West into his error about the ability to dispense with continence.

Karol Wojtyla/JPII's treatment of shame suggests otherwise. In Love and Responsibility [LR], he explains that shame has a two fold purpose. Negatively it moves us toward modesty in dress and behavior. Positively, it reveals the intention of affirming value of the whole person. Wojtyla writes, for authentic love to exist shame must always be preserved intact (see LR, 182). In fact, the importance of shame for healthy relationships is such that if the sense of it is lost, it must be recovered through education (LR, 186).

Ultimately, West's view about liberation from continence contradicts Catholic tradition; something John Paul II never does. Rather, John Paul synthesizes the tradition with new insights from phenomenological personalism, though mature purity is not a new insight. It is an articulation of St. Thomas Aquinas's anthropology.

What John Paul II actually means by liberation is from the "constraint of the body" which arises with the advent of concupiscence (TOB 32:2). The constraint of concupiscence makes authentic total self-gift virtually impossible (TOB 32:6). He also uses constraint to describe the instinct of animals who cannot but follow their urges (TOB 14:6). Something like constraint to instincts is what happens to the man of concupiscence. This constraint is insuperable until the advent of Redemption. However, liberation from this constraint is not the same as near immunity from concupiscence for those who have become "pure" as West puts it.

John Paul holds to tradition saying that "immediate continence," together with self-mastery and habitual temperance are all simultaneously needed to live the ethos of redemption (see TOB 49:4, 53:5). Continence is "a definite and permanent moral attitude, a virtue" (TOB 124:4; emphasis mine). He doesn't say continence can ever be set aside.

West says he will not limit the power of God's grace. This is true, but there is another error, the sin of presumption. Neither may one presume upon God's grace, much less put it to the test. Surely, God provides all we need for purity but he doesn't always heal so there is no struggle (see 2 Cor 12:9). Just as He doesn't always heal bodily ailments, neither does He always heal wounds of the soul but allows them that greater good may come. In fact, Thomas indicates there can sometimes be greater merit in the struggle than in natural virtue (see ST II-II, q. 155, a. 4, ad. 2).

Concluding Thoughts

Christopher West rightly teaches John Paul's articulation of the good news for the man of concupiscence. He can liberate himself from the constraint of concupiscence though not its continual draw. But he is wrong to suggest one may reach a point at which he need not exercise continence. This is not what John Paul II means by mature purity and it can lead to serious problems for some.

I pray that with Christopher West's return, he will continue to teach the truths as he has done so well. However, I also pray that he publically corrects his errors. His mistaken implications of mature purity may have led him to believe that modesty and restraint are not necessary in his teaching if one is pure, but this is not so. He also seems to think that purity of intention is all that is required for the morality of action; this is also a serious error. I would urge him not only to appropriate John Paul II's content, but also his restrained and modest style and his organic integration of the tradition.

[Note: The last sentence has been removed as it did not adequately convey what I intended and can (was) taken as unnecessarily critical.]

"Virtue, Continence, and Concupiscence" a response by Janet Smith

Prof Delaney has provided an opportunity for a conversation about the question of Christopher West's treatment of concupiscence. It is refreshing to find a conversation filled with courtesy, on having a focus on the issues and on getting the terms straight. Here is more a search for truth than an attempt to condemn. To test the charges against West will require a careful reading of what he says and I am sure he or his defenders will undertake that task. But it is even more wonderful to see the discussion focusing not on West says but on what the truth is. Let me add a few not completely random comments to the discussion.

One point of possible confusion that has tripped up a few in the discussion is that the word "continence" can mean a state that is not yet virtue.

Aristotle (followed by Aquinas) identified a "state of character" he called continence. It was a state that generally kept a person from wrong behavior but was not the same as virtue. The continent person still struggles with temptation; this person generally does the right thing but sometimes with some struggle. This would be the man who wants to be faithful to his wife but is still strongly attracted to other women. He needs to be careful to avoid the occasion of sin. He can't trust himself to spend long hours having drinks with an attractive woman. Since he knows this about himself he avoids such situations. Although he is generally happy when he avoids serious sin, he also somewhat regrets the pleasure he would have enjoyed had he sinned. This person does not yet have virtue; he has only continence. Working at strengthening his love and commitment to his wife would be necessary for growth in virtue; avoiding temptation simply keeps him from serious sin.

I sometimes think virtue is like that: when faced with something one knows would be pleasurable if one were able to partake of it, one is not really attracted because it would be harmful or ruin good things in one's life. So while there may be some "attraction" there is no real temptation. |

Aristotle thought few people could attain the mastery over the passions necessary to have the state of character he called virtue. Let's consider the virtue of temperance. Having temperance means being able to quickly and easily overcome temptation, to the point where it is hard to say that there is any temptation at all. This person has a very strong attachment to what is good. Consider here a married man powerfully in love with his wife and totally committed to fidelity. He believes that any lustful looks towards another woman are a serious violation of his relationship with his wife. He seeks to avoid any looking at women or thinking about women that would even begin to send him down the road of sexual thoughts, thoughts that would have him starting to have a fantasy of another woman unclothed or the desire to touch the woman in certain ways. This man takes great pleasure in his self-mastery and does not regret the pleasures he would have enjoyed had he sinned. Those illicit pleasures now are quite repugnant to him.

I think it is right to interpret Aristotle as holding it is possible that a man could get to the state that routinely his thoughts around an attractive and modest women would be: "she has invited me to respect her by her modesty and I can certainly do that; I will only think of her as lovely and beautiful and not have sexual thoughts about her." I think it is right to interpret Aristotle to hold that it possible that a man could get to the state that routinely even when alluring and immodestly clad women are in his company, he could easily turn his eyes and thoughts away from sexual values, by thinking: "What does this have to do with me? I am dedicated to my wife." Yet, it would be the rare man in Aristotle's view who could do so. (Below I will explain why it is easier for a Christian to do so.)

Is it an act of concupiscence to recognize that a woman is attractive? Or even that the alluring and immodestly clad woman is both alluring and scantily clad? Sometimes I wonder if true virtue is somewhat like a "healthy" allergy. I have an allergy to food items made from wheat flour pizza, cookies, pretzels, etc. When I eat them I have a fairly severe reaction, to the extent that although I still respond favorably to the smell of such items, I have no desire to eat them. They attract and repel at the same time. I sometimes think virtue is like that: when faced with something one knows would be pleasurable if one were able to partake of it, one is not really attracted because it would be harmful or ruin good things in one's life. So while there may be some "attraction" there is no real temptation. I have spoken with married people who say they are simply not tempted to commit adultery or even to think lustful thoughts or even fairly mild sexual thoughts about others. Yes, they recognize that this or that individual is attractive and can experience a little charge of attraction now and then but they quickly turn their thoughts back to what is important: I am married and not to this person.

Several of the commentators on Delaney's blog inquire about what is a male to do who is around beautiful scantily clad women, such as athletes or dancers. (Certainly, such women should try to find modest clothing in which to conduct their activity but given the world in which we live, such is not likely.) I think the Theology of the Body provides some guidance. John Paul II believes that the proper understanding of the dignity of the person and the meaning of sexuality should help one learn to control one's sexual thoughts. If one looks upon the other as a person to be valued and not as an object to be used, if one understands that sex belongs within marriage and has a procreative purpose, one is less likely to seek sexual pleasure outside of marriage or even to have lustful thoughts. In the portion on the Song of Songs, JPII speaks much about how the lover speaks of his beloved as his "sister". Many men eventually learn to look upon women as "sisters" and "daughters"; they would never want to think about their sisters and their daughters in a sexual way. Many of the coaches who can work with beautiful young women can do so while preserving chastity because it is always in their minds "this girl could be my daughter." Many pure men remain pure by looking away from anything such as ads or movies that are likely to arouse their sexual desire; they come not to enjoy experiencing sexual pleasure apart from their relationship with their wives. They seem to me to have an easier time looking at real, beautiful women than those in movies, etc, because it is easer to see the real woman as a real person, as a daughter or sister.

He made the blind see, the deaf walk and the dead come back to life. What limitations are there on his abilities to order our desires? If we pray and receive the sacraments and develop good habits should we not have some confidence that we can overcome temptation? We are not depending upon ourselves, but on Christ within. |

One reason virtue was so difficult for the ancients was that they had to depend entirely upon their own powers to discipline themselves; they didn't have the access to grace that Christians have. Jacques Maritain spoke of the "moral athleticism" required by ancient virtue ethics; we are always attempting to ascend, to climb a high mountain. Christians are both more optimistic and more pessimistic than Aristotle. After all, our Lord descended from the high heavens to bring graces to us to make easier what was difficult and possible what was impossible. He made the blind see, the deaf walk and the dead come back to life. What limitations are there on his abilities to order our desires? If we pray and receive the sacraments and develop good habits should we not have some confidence that we can overcome temptation? We are not depending upon ourselves, but on Christ within.

On the other hand, Christians believe in the devil who seeks the ruin of souls. Those who are not living strong Christian lives and who depend too much upon their own powers likely are going to succumb to temptation. Most Christians are going to need to remain cautious and not be foolish in putting themselves in situations likely to arouse lust. For a long time, most people have only continence not virtue. But Catholics who practice their faith devoutly by receiving the sacraments, praying regularly, and striving for growth in holiness, may in fact find that they have the virtue of chastity and will enjoy great freedom from temptation even in objectively tempting situations. Sin and even temptations to sin have become unattractive to them.

Of course, even saints can be tempted but their temptation is likely of another kind. Those who have achieved holiness, those who are saints because of rigorous prayer and fasting are likely spectacularly free from temptations to sexual sin; their temptations are likely more to pride, etc. Yet saints on occasion are going to be subject to severe sexual temptation not because they don't have virtue or mastery over their passions, but because the devil will attempt to stir up any trace of concupiscence that remains in their system. He has greater mastery over matter than spirit so he can more easily make inroads in the sexual sphere, particularly when people are tired or lonely. Even under severe temptation saints will rarely fall both because they can depend upon their virtue and because God will give them the power to resist. The struggle they undergo is less a testimony to the power of the remnants of concupiscence in their systems, than the power of the devil.

I know a man who had been a sex addict who after his conversion led a very penitential life. First he nursed several family members through years of dying and then he moved from his luxurious home to an inner city house where he lived in one room and slept on the flour. He had an apostolate to prostitutes. He led others, two by two, to go out in the streets and take the women items they might need and to pray for them and their needs. There was no hint that he had the slightest sexual interest in them. His response to them was suffused with compassion. Grace works miracles. And perhaps Christians are wrong to think that miracles are rare.

So I think there is a great deal to keep in mind. The "fomes" or embers of original sin likely remain in even the most saintly but also likely for the saintly require the force of the devil to foment. The virtuous have been vigilant over what might provoke sinful thoughts in them and know how to banish them, perhaps especially in situations that might provoke serious temptations to sin. Most faithful Catholics who are living by the laws of God and the Church, receiving the sacraments of the Church, developing a strong prayer life and finding a good circle of friends, are not going to be tormented by sexual desire in any regular fashion. I think it not so rare that truly practicing Catholics achieve a remarkable grace-filled freedom from concupiscence. So when we are discussing what power over concupiscence people can have, many factors come into play.

"Setting aside Continence" a response by Janet Smith

Prof. Delany is to be commended for his desire to get to the bottom of Prof. Schindler's concern about West's position on concupiscence and continence. Schindler made only an accusation; he did not make a case for his position. Delaney does and that is a service, as is his clear attempt to remain respectful.

Delany seems to have three major problems with West's position:

- He doesn't think that West recognizes the continued problem with concupiscence that remains even in the most virtuous, even in those with "mature purity".

- He thinks that West is wrong to think "mature purity excludes continence."

- He thinks that West may be advising imprudent behavior for those who have attained mature purity.

I think West's views properly understood should not raise any of those concerns. Certainly his presabbatical statement on concupiscence very faithfully follows John Paul II. Those who have trouble with that statement have trouble with the positions of John Paul II.

Liberation from Domination of Concupiscence

1) Delany compliments West for having clarified that in the past he had not given sufficient attention to the fierce character of concupiscence, but does not find his clarification sufficient. Delaney continues to charge: "Nevertheless, he doesn't retreat from his emphasis that redemption brings about liberation from concupiscence." But West says this:

"It is abundantly clear from both Catholic teaching and human experience that, so long as we are on earth, we will always have to battle with concupiscence that disordering of our passions caused by original sin (see Catechism of the Catholic Church 405, 978, 1264, 1426). In some of my earliest lectures and tapes, I confess that I did not emphasize this important point clearly enough. The battle with concupiscence is fierce. Even the holiest saints can still recognize the pull of concupiscence within them. Yet, as John Paul II insisted, we "cannot stop at casting the 'heart' into a state of continual and irreversible suspicion due to the manifestations of the concupiscence of the flesh Redemption is a truth, a reality, in the name of which man must feel himself called, and 'called with effectiveness'" (TOB 46:4)."

There are some important distinctions here. West says "we always have to battle with concupiscence." How can he be said to hold that "redemption brings liberation from concupiscence?" if we always have to battle concupiscence? West repeatedly says that "mature purity" liberates us from the "domination" of concupiscence. That is a very precise and important point. We will always have concupiscence lurking in the depth of our being, but those who have responded to the graces of redemption will be free from the "domination" of concupiscence. When West quotes John Paul II speaking of a "victory" over concupiscence, West tells us "victory" does not mean we totally overcome concupiscence; rather the victory is still "fragile."

I see no reason to hold that West believes we can be completely liberated from "concupiscence", only from the "domination of concupiscence."

Delaney thinks that West is wrong to think "mature purity excludes continence." He does not give us any reference to a passage where West says this. Does he? Where? On the basis of what does Delaney make this charge?

Continence as distinct from Mature Purity

A great deal of the difficulty about the question of the continued need for continence comes from the wide variety of ways in which the word is used. As I noted in my previous piece, in the Thomistic tradition (and John Paul II considers himself a Thomist) continence is one thing and virtue or mature purity is another. West, following John Paul II, uses the phrase "mature purity" to refer to the state of virtue. The man of continence does not yet have the joyful, peaceful control of his passions had by the man of "mature purity." Both the continent man and the man of mature purity have control over their passions, but the continent man struggles with temptation and the virtuous man does not. The continent man to some extent still wishes he could give in but he knows he shouldn't. The man of mature purity takes joy in being able to contain his passions and experiences a peace not yet known by the continent man.

Neither Aquinas or John Paul II are completely consistent in their use of the term "continence" and therefore some confusion about what Aquinas and John Paul II are saying is understandable. Looking closely at context can often clear up confusions. I think Delaney occasionally succumbs to various confusions.

Delaney's statement that West claims "that we must reach a state in which we no longer resort to continence." (Does West say that? Where?) I don't understand this claim. I don't know what it means to speak of "resorting" to continence in this context. Continence is not something to which one "resorts." It is a condition. The condition of "mature purity" is higher and stronger than continence. The man of mature purity has even greater control over his passions than the man of "continence." It makes no sense to speak of the man of "mature purity" as having to "resort" to continence. Certainly he controls his passions, but with an ease not known to the man of "continence."

Delaney notes that John Paul II also calls "continence" a virtue. And he does do that. Indeed that truth makes the statement about the man of virtue needing to resort to continence meaningless. The man of virtue is the man of continence but much more. He doesn't need to "resort" to continence because he has all the power that continence provides plus more.

Authors often use a word in one sense in one context and another sense in another context. John Paul II uses continence in many senses; he uses it to refer to control of any passion; he uses it to refer to the periodic "continence" or abstention involved in using Natural Family Planning (e.g., 124:2) he uses it to refer to the state of celibacy (73ff), and sometimes he uses it synonymously with "self-mastery" (127:4ff). That can get confusing. He also uses "temperance", "self-mastery", "mature purity," "continence" and "abstinence" synonymously (see 53:4 and also all of 54). What is to the point here is that sometimes John Paul II distinguishes temperance from continence (this seems to be the case at 49:5) and sometimes he equates them (this seems to be the case at 53:5 and especially in 127:4ff).

Delaney charges that West holds that the man of mature purity is free to "set aside" continence but gives us no citation where he says that (perhaps he will in his published article; it is essential that he do so; otherwise he has set up a straw man.) Again, understanding "continence" as a state of character rather than as the act of either abstaining from sex or the act of struggling with desire, it does not work to speak of "setting aside" continence. The man of virtue, the man of self-mastery, the man of "mature purity" most certainly has struggled with sexual temptation, but John Paul III believes that some individuals can attain a state where that struggle is not a constant reality for them and in fact is a rare one.

Rather than showing that West argues that we can "set aside continence" Delaney seeks to show that John Paul II never advocates "setting aside" continence. He cites 49:5 to make his point. That passage shows how much John Paul II mingles many concepts sometimes not making clear whether he is talking about distinct realities or whether he is being pleonastic. There he says:

The form of the "new man" can come forth from this way of being and acting in the measure in which the ethos of redemption of the body dominates the concupiscence of the flesh and the whole man of concupiscence. Christ shows clearly that the way to attain this goal must be the way of temperance and of mastery of desires.The ethos of redemption contains in every context and directly in the sphere of the concupiscence of the flesh the imperative of self-mastery, the necessity of immediate continence, and habitual temperance.

Are "temperance" and "mastery of desires", two virtues or the same virtue or one "broad virtue" (mastery of desires) and one subordinate virtue (temperance or mastery of sexual desire)? Are "self-mastery", "immediate continence" and "habitual temperance" three different states or the same state? What John Paul II is teaching in these passages wherein he uses an array of terms is in no way incompatible with West's presentation of his position. Self-mastery, continence, and habitual temperance (that surely is a pleonasm since all virtue is a habit) will all enable one to bring the graces of the redemption to one's interaction with the opposite sex.

Continence and Virtue as the Same State of Character

John Paul II has a long section (127:4ff) where he precisely identifies continence as a virtue and that virtue is the same as self-mastery. Here he is talking about the virtue of continence that spouses achieve when they practice continence understood as abstention from the sexual act. When that abstention is properly ordered by an understanding of the spousal meaning of the body, spouses can achieve the virtue of continence. John Paul II speaks of this continence as giving spouses "mastery over concupiscence." (127:4) He defines continence in this way: "'Continence,' which is part of the more general virtue of temperance, consists in the ability to master, control, and orient the sexual drives (concupiscence of the flesh) and their consequences in the psychosomatic subjectivity of human beings. As a constant disposition of the will, such an ability deserves to be called virtue." (128:1) The word "mastery" and phrases such as "free from tensions" (129:1) keeps appearing through the text. Certainly couples may struggle with having to abstain from sexual intercourse during the fertile times, but the state of control that they eventually achieve is a virtue. (130:5)

John Paul II faces squarely the question "Is continence (here the same as self-mastery) possible?" (129:2) He makes an extremely important distinction. He distinguishes between "arousal" and "emotion." He states that arousal is "bodily and sexual," whereas emotion is stirred by the reciprocal reaction of the masculinity and femininity [and] refers above all the other person understood in his or her 'wholeness.' One can say that this is an "emotion caused by the person" in relation to his or her masculinity or femininity." Here he is discussing how spouses will experience both but it is a distinction that can be used for virtuous male/female relationships in general. I have heard that John Paul II, surely a man of continence, self-mastery, temperance, and mature purity, lit up in a special way when greeting a beautiful woman. That reaction was emotion not arousal.

3) Delany spends some time discussing what behavior West thinks possible for those who have achieved "mature purity." He seems to acknowledge that West is not advising imprudent behavior but still has difficulty with West's confidence in people's ability to be free from concupiscence.

He tells us that West believes that "mature purity" means that "Rather than turning away from temptations, it is an achievement in which one no longer need turn away." Delaney gives us no passages where West says this. He certainly doesn't say this in his presabbatical statement. There West says, "For those graced with its fruits, a whole new world opens up - another way of seeing, thinking, living, talking, loving, praying. But to those who cannot imagine freedom from concupiscence, such a way of seeing, living, talking, loving, and praying not only seems unusual - but improper, imprudent, dangerous, or even perverse."

I recently heard from a Christian father who is trying to teach his teenage son how to look upon women with respect. He told him that every woman has a special gift that God has given her a gift that allows men to look upon her as a person and not as a sexual object; something special and something lovable. He told him that this is true of every woman, of the overweight, the homely, the aged, as well as the young and beautiful and he has challenged his son to see if he can see it in the particular women he encounters. The father reported to me that his son is growing in tremendous respect for all women and learning to look past the "packaging" to the person. This seems to me to be what West is trying to teach men and women to do.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

David Delaney & Janet E. Smith. "Concupiscence in the West-Schindler Debate." cosmos-liturgy-sex blog (October 10, 2010).

Offered with permission of Janet Smith and David Delaney. Read the whole discussion here.

The Author

Janet E. Smith holds the Father Michael J. McGivney Chair of Life Ethics at Sacred Heart Major Seminary in Detroit. She is the author of Life Issues, Medical Choices: Questions and Answers for Catholics, Beginning Apologetics 5: How to Answer Tough Moral Questions–Abortion, Contraception, Euthanasia, Test-Tube Babies, Cloning, & Sexual Ethics, Humanae Vitae: A Generation Later and the editor of Why Humanae Vitae Was Right. She has published many articles on ethical and bioethics issues. She has taught at the University of Notre Dame and the University of Dallas. Prof. Smith has received the Haggar Teaching Award from the University of Dallas, the Prolife Person of the Year from the Diocese of Dallas, and the Cardinal Wright Award from the Fellowship of Catholic Scholars. She is serving a second term as a consultor to the Pontifical Council on the Family. Over a million copies of her talk, "Contraception: Why Not" have been distributed. Visit Janet Smith's web page here. See Janet Smith's audio tapes and writing here. Janet Smith is on the Advisory Board of the Catholic Education Resource Center.

Copyright © 2010 cosmos-liturgy-sex blog