How the Church has changed the World: Man, the Incurable

- ANTHONY ESOLEN

It was Good Friday, 1859.

Join the worldwide Magnificat family by subscribing now: Your prayer life will never be the same!

"Father," said the little girl, tugging at his hand, while thousands of people around them were muttering prayers in a language she didn't know, "who is that man all in white on the balcony?"

"Rosebud, that is the Papa." Her father smiled proudly upon her. He loved his children dearly, and they in turn looked upon him as a tower of wisdom and a child younger than they.

"Is he the father of all these people?"

"He is indeed."

Her father was not a Roman Catholic, though the artist in him, for he was one of the most precise and profound artists the English language has known, felt at home here in a way that was otherwise inexplicable. It was not the food, which he didn't care for, or the heat and the bright glare of the sun, so different from the cool of New England, or the lustrous-haired natives, openly selfish and openly devout, utterly unlike the well-educated and eloquent men and women who formed his family's wide circle of friends, people such as Emerson, Thoreau, Bronson Alcott, Ellery Channing, Margaret Fuller, and his brother-in-law Horace Mann.

He knew, and said so, that Rome was truly the Eternal City, because in Rome met all that was greatest, most intelligent, most wicked, and most blessed in the story of man. He was then writing a novel about the famous "Barberini Faun," a marble statue of a drunken satyr, and its power of influence upon a group of young American tourists and artists.

"Rosebud," he said, "would you like to have a medallion of the Papa?"

"Oh father, may I? He is so beautiful all in white." That impression, mingled with joy, remained with her all her life. So did the medallion.

All Roads Lead to Rome

Little Rosebud's mother and father, as we can tell from the letters she published after they had passed away, were deeply religious people, yet homeless in the Christian faith. Her father was a descendant of the first Puritans, and one of his ancestors had played a notorious part in the Salem witch trials. He was always aware, painfully so, of the insufficiency of man. When he was courting Rosebud's mother, Sophia, then living with her family among the transcendentalists at Brook Farm, he was, as Sophia said, a gentle observer, but never a comrade. Later, during the heat of the abolitionist movement, he wrote frankly to his sister-in-law Elizabeth, who had published a tract, which he said was not very good, judging it to be born of single-minded and squint-eyed zeal.

I mention this because Rose Hawthorne inherited from her father that same sober awareness of the existence of evil in the heart of man, and his conclusion that the evil was incurable by any other than God himself.

I mention this because Rose Hawthorne inherited from her father that same sober awareness of the existence of evil in the heart of man, and his conclusion that the evil was incurable by any other than God himself. Yet her father was the kindest and most cheerful of men. Perhaps we may draw here the conclusion that the most tolerant people in the world are saddened by sin, which they recognize, while those who believe that man is perfectible — and that they know how to do the trick — are the quickest to condemn and to shed blood when reality proves otherwise.

Life around their family hearth was rich in games and music and foolery, but also, note well, in the reading of great works of literature. That was, we may say, the television of their time. Nathaniel and Sophia Hawthorne read Spenser aloud, and Shakespeare, and Milton, and Dickens' David Copperfield, and the poetry of Tennyson, whom they saw in person in England, and of the Brownings, whom they got to know well in Rome. They named their first child Una, after the heroine of Spenser's Faerie Queene, and when Nathaniel first met Sophia, she was in the middle of painting Una and Saint George and the Dragon.

If you were immersed in such art, in that atmosphere, I think there were only two directions you could take. You could lose your faith and become a philanthropic aesthete, or you could throw yourself back into the old religion. Which of these paths Rose took can be inferred from this remarkable passage:

"In art, Catholicity was utterly bowed down to by my relatives and their friends, because without it this great art would not have been. For, as scientists and dreamers have proved that gold cannot be made until we know as much as the earth, so uninspired artists have proved that religious art can only grow under conditions known solely to the heart that is Catholic. Every religious school of art which has departed from imitation of the Old Masters has forfeited holiness in depicting the Holy Family."

In 1891, Rose Hawthorne Lathrop and her husband, George, were received into the Catholic Church.

Bring me your huddled masses

The Lathrops' marriage was not a happy one. They had had one child, Francis, who died of diphtheria when he was still a small boy. George was a writer of some note, the editor of The Atlantic Monthly, and he and Rose were active in work for charity. But after Francis died, he took to hard drinking and irresponsible spending. Rose finally received permission to separate from him; he died of cirrhosis in 1898.

One of Rose's good friends in the literary world was Emma Lazarus, the poet whose sonnet of welcome, inspired by Russian pogroms against the Jews, was later inscribed on a plaque at the base of the Statue of Liberty. In 1887, she lay dying of cancer, at the age of thirty-eight. Rose was with her in her last days, and wrote that she felt sorrow for her but not pity, because Miss Lazarus had been surrounded with all the comforts that medical science then could provide for her.

It was then that Rose Hawthorne first conceived of the idea of a ministry to people dying of incurable cancer.

But Mother Mary Alphonsa loved those whom no one else would love: men and women disfigured by cancer, and approaching an inevitable death.

It seems strange to us now, but at that time people thought that cancer was communicable, and that was why no hospitals would take you in if you were suffering from it. Let us not blame them too harshly. I have read a newspaper article from those days that predicted real hardship in the region's hospitals for the coming year, because the winter had been too warm, so that ice to treat fevers would be in short supply. Before Pasteur, nobody believed that disease could be spread by microscopic organisms; after Pasteur, it seems that everybody believed it, even when sometimes it was not so.

Still it was a cruel thing, to be disfigured by cancer and not to have anywhere to go, unless you were rich. And few people are rich.

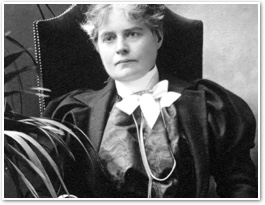

So in 1896, Rose Hawthorne took a course of nursing in New York, aiming to tend to people whom no one else wanted. She took up a flat and welcomed the incurable into her home, feeding them and cleaning their sores. To raise money she wrote those reminiscences of her beloved father and mother, which I have quoted above. Then in 1900 she and two of her companions were invested as tertiaries of the Dominicans: the Dominican Congregation of Saint Rose of Lima, named for the holy woman of Peru who ministered so lovingly to the poor. They were also called the Servants of Relief for Incurable Cancer. Her father would have admired the name and the mission.

Rose, now Mother Mary Alphonsa, described their work thus: "To take the neediest class we know — both in poverty and suffering — and put them in such a condition that if our Lord knocked at the door I should not be ashamed to show what I have done. This is a great hope."

Until her death in 1926, that is what she did, and she never took a cent from the government or from those she served. She did not wait for money before she acted. She took as her motto that of Saint Vincent de Paul, "I am for God and the poor." Her cause for beatification is underway.

Not philanthropy, but love

One day a reporter saw Mother Teresa cleaning the pus-leaking sores of a man dying in the streets. The sores stank to high heaven.

"I wouldn't do that for a million dollars," said the reporter.

"Neither would I," said Mother Teresa.

Mother Mary Alphonsa, Servant of God, did not love man in the abstract. Nor did her father, the great novelist. It is easy to love man in the abstract; all you have to do is imagine him to be lovable, in person and disposition, and then keep that image before your eyes, while keeping the reality at a comfortable distance. Anyone can love mankind. It is your neighbor ten feet away who is hard to love, sometimes impossible to love without the grace of God.

But Mother Mary Alphonsa loved those whom no one else would love: men and women disfigured by cancer, and approaching an inevitable death. Such courage defies explanation; as does the love of Christ.

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Anthony Esolen. "How the Church has changed the World: Man, the Incurable." Magnificat (September, 2018): 200-205.

Anthony Esolen. "How the Church has changed the World: Man, the Incurable." Magnificat (September, 2018): 200-205.

Join the worldwide Magnificat family by subscribing now: Your prayer life will never be the same!

To read Professor Esolen's work each month in Magnificat, along with daily Mass texts, other fine essays, art commentaries, meditations, and daily prayers inspired by the Liturgy of the Hours, visit www.magnificat.com to subscribe or to request a complimentary copy.

The Author

Anthony Esolen is writer-in-residence at Magdalen College of the Liberal Arts and serves on the Catholic Resource Education Center's advisory board. His newest book is "No Apologies: Why Civilization Depends on the Strength of Men." You can read his new Substack magazine at Word and Song, which in addition to free content will have podcasts and poetry readings for subscribers.

Copyright © 2018 Magnificat