Special Olympics, special children

- FATHER RAYMOND J. DE SOUZA

The joy of the Special Olympics is infectious; everyone who volunteers knows that it is a privilege to be part of such a great celebration of exuberant life.

|

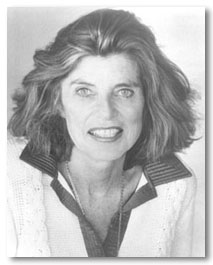

Eunice Kennedy Shriver |

The national Special Olympics are underway in Brandon, Manitoba and it’s a safe bet that the athletes’ village at Brandon U. might just be the happiest place in Canada this week. The joy of the Special Olympics is infectious; everyone who volunteers knows that it is a privilege to be part of such a great celebration of exuberant life.

The Special Olympics have never been bigger, expanding all over the world. But the future of the “special” children it was founded to serve may not be so bright.

Ten days ago, President George W. Bush held a gala dinner at the White House to honour the founder of the Special Olympics, Eunice Kennedy Shriver, on her 85th birthday. In 1953, Eunice married Sargent Shriver, future founder of the Peace Corps and Democratic candidate for Vice President. Eunice and Sargent actually lived out the image carefully crafted for her more famous brothers — the happy clan devoted to faith, family and honourable public service.

Mrs. Shriver will forever be the sister of JFK, RFK and Teddy, and latterly the mother-in-law of Arnold, gubernator of California, but it was her older sister who most influenced the course of her life. Suffering from mild mental disability or mental illness, a 23-year-old Rosemary underwent a lobotomy that reduced her to an institutionalized state for her entire life (she died last year at age 86). Mrs. Shriver, horrified at the condition in which the mentally disabled lived, founded the Special Olympics to give such children what all children want — the opportunity to play, to strive, to compete and to be recognized. The first Special Olympics in 1968 took place in an empty Soldier Field in Chicago; today it has captured the hearts of millions worldwide.

The Shrivers are also heroes of the pro-life movement, a position which puts them at odds with the Senate’s greatest enthusiast of the unlimited abortion license, brother Ted. The Shrivers are a living refutation of the accusation that pro-lifers only care about children “before birth.” The belief that every life is sacred animated not only Eunice’s Special Olympics, but also Sarge’s public policy work in the heyday of liberalism: Head Start, Peace Corps, Job Corps, Foster Grandparents, and the like.

The term “special” likely emerged from how disabled children were spoken about by their parents a few generations back. Speaking of the “special child” could be a patronizing euphemism, but parents themselves used it because they quickly realized that the mentally disabled were special gifts indeed; burdens at times, but blessed burdens — not unlike children in general.

Baby Smyth was not treasured, was not special enough. She would not grow up to be an athlete, so perhaps it would be better if she did not grow up at all. Mrs. Shriver, who made her home a summer camp for mentally disabled children in 1962, founded the Special Olympics precisely to counter that way of thinking. |

Today, the terminology has changed. The “special” child is the highly-desired — and sometimes quasi-engineered — child. Special means something like perfect, or at least not disabled. Increasingly those who are not perfect never see the light of day, let alone grow up to be Special Olympians.

“The geneticist quietly tells us our child will be significantly lower functioning than other children,” wrote one C. Smyth last week in The Globe and Mail, describing her decision to abort her child. “Definitely not the treasured only child, the little athlete, we had only so recently and so tentatively allowed ourselves to dream about.”

Baby Smyth was not treasured, was not special enough. She would not grow up to be an athlete, so perhaps it would be better if she did not grow up at all. Mrs. Shriver, who made her home a summer camp for mentally disabled children in 1962, founded the Special Olympics precisely to counter that way of thinking. The principal difference was that such children in 1962 were not subject to the geneticist’s diagnosis as death sentence.

“We don’t feel capable of raising a severely disabled child,” wrote C. Smyth. “It would be different if we didn’t have a choice, but we do.”

The “severe” disability the Smyths were confronted with was Triple-X syndrome, not as serious as Down syndrome. Of course, you don’t see a lot of Down babies any more; many don’t make it out of the womb.

Special Olympics are also for parents and would-be parents like C. Smyth. No one feels capable of raising a disabled child in anticipation. No one looks forward to it per se. But most such parents, perhaps because they didn’t have a choice, have discovered what is so evident in Brandon this week, namely that the mentally disabled in our midst are a treasure — special indeed.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Father Raymond J. de Souza, "Special Olympics, special children." National Post, (Canada) July 20, 2006.

Reprinted with permission of the National Post and Fr. de Souza.

The Author

Father Raymond J. de Souza is the founding editor of Convivium magazine.

Copyright © 2006 National Post