Slave of the Ethiopian Slaves

- ANTHONY ESOLEN

"This book was owned by the happiest man in the world."

Join the worldwide Magnificat family by subscribing now: Your prayer life will never be the same!

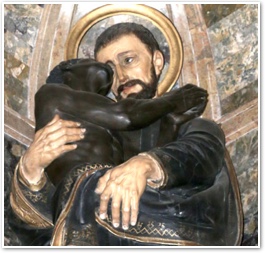

Saint Peter Claver, S.J.

Saint Peter Claver, S.J.1580-1654

Before I tell who wrote that, we might wonder what would justify such a claim. Was the man rich, admired, the father of many children? Did he enjoy the pleasures of the world in moderation, living to a good old age and dying peacefully, as a ripe apple drops softly from the tree?

Saint Peter Claver was none of those things. He could have lived the comfortable life of a wise and kindly teacher at Montesión, the Jesuit college in Palma, on Majorca in the Mediterranean. Think of that for a moment. Fresh salt breezes, palm trees, no snow, no swelter; and Spain, your homeland, a short voyage away.

You could achieve holiness in Palma, too.

The elderly doorkeeper at Montesión did. We honor him as Saint Alonso Rodriguez. Alonso was a widower who gave up his life in the world to join the Jesuits. For twenty years he kept the door, he was the first and immediate servant of all who came to visit Montesión. The world would not now appreciate a man like Alonso, with his childlike humility and docility. But Peter Claver understood him. They became fast friends. It was Alonso who told Claver that the harvest was plentiful in the New World, especially among the poor Africans transported there by the slave ships, and that he should appeal to his superiors to send him. Father Claver, in his humility and docility, had balked at urging it too boldly.

They were alike, these two. Alonso's job was utterly mundane, nothing spectacular about being a doorkeeper. But his childlike sweetness and his unceasing life of prayer won the hearts of all who met him. Meanwhile it was said of Peter Claver that he was a novice from first to last. He never questioned a command, so his superiors never needed to worry about who would clean the latrine or the stables. They had only to ask Father Claver.

So he did as Alonso recommended, and two years later he found himself in Cartagena, the swarming slave port on the Caribbean.

Light in darkness

"Hurry, son," says Father Claver, his shoulders bearing one end of a pole upon which are slung big baskets of fresh vegetables, lemons, bread, flasks of wine, bandages, and other necessaries. "They've already arrived! Let's not be late!" His eyes are wide with good cheer, as if he were a boy running to the carnival.

"Yes, Father," says the young Jesuit at the other end of the pole, his knees buckling and his shoulder chafing against the wood. He can hardly keep up.

That was Peter Claver's routine for thirty-five years. Nobody knew how he managed it, since he slept very little and ate only one or two pieces of bread and some fried potatoes each day. Love and holiness were like fire in his veins, giving him a stamina that was supernatural. He did not waste away, or succumb to scurvy from his bad diet, or contract the diseases that riddled the wretches he served.

"Here they are!" he cries, as more than a hundred miserable human beings are led staggering from a ship by their guards.

Imagine the horror. The Africans are naked — men, women, and children. The men are in chains. A third of them died at sea. They were cramped below deck to eat and drink and evacuate themselves, stewing in their filth, puking from the stench and the rolling sea, ravaged with dysentery, the men's legs ulcerous from the shackles; blood and mucus soaking the floors; fed nauseating stuff and flogged if they refused to eat it knowing nothing of what was happening to them or why.

It is the hell on earth that men make for one another.

Then they meet Father Claver.

The slave traders were horrible Catholics, but they let Claver do his work.

He smiled upon the Africans, speaking to them in Angolan Portuguese, using African interpreters for a few other languages, but mainly communicating in the universal human language of gentle touches, to comfort them, soothe them, give them heart.

He fed them the first good food they had had since they were captured. He washed their wounds with wine. He cleaned the filth from their bodies. He bound up their sores. He clothed their nakedness. The stench was so choking that no one but Claver could endure it for more than a few minutes. He didn't notice it, or if he did, he took it as a gift from God.

He kissed them. He sucked the poison from their sores, the way you'd suck the venom from a snakebite — but this poison was from disease and putrefying flesh.

If they could not walk, he carried them. He made carts for the sick so they would not have to hobble along under the lash. To those who were dying he ministered first of all, ready with the water and oil of baptism, if they could be made to understand the merest notion of their sin and of Christ's salvation.

In the days when they were herded into barracks before being sold, Claver would preach the Gospel, using for illustration a medal of Jesus and Mary that his friend Alonso had given him.

"If the Spanish are in heaven," a native once said, "let me go to hell, so I will not have to see them anymore." He could not have been referring to Peter Claver. The blacks never said, "He is one of our tormentors." They listened to him. Africa had its own horrors, and Africans were sinners too.

Only a love beyond human reckoning could have won their hearts. It is a love that the world does not know how to give, a love the world had never heard of before Christ.

Among the lepers

"Humanitarianism," said Walker Percy, "leads to the gas chamber" Peter Claver was not a mere humanitarian. He had no agenda for the social improvement of man. He was consumed with love for the individual, and the more miserable and needy, the more ardent was his love.

The humanitarian does not sit at the bed of a dying man; he gives him morphine to be rid of him most efficiently. But human beings are not objects of efficiency. Jesus would have borne the cross for one sinner alone. Was that efficient? He suffered and died for Alonso and Peter and you and me, individually. All of that, because he wanted our friendship.

Lepers will flush out the humanitarian from his covert every time. See the grotesque disfigurement; fingers, noses, ears missing; the glorious human body reduced to dots, cleft and pocked and burst open like rotten fruit. Only a saint would go among lepers. Many of the slaves had contracted leprosy, and were sent to live out their last days in a colony. Claver went among them.

Of course in those days there were no latex gloves, goggles, and antiseptics. We can imagine a very good person in our days on a temporary mission, bolstered with the protections of modem industry, going among lepers, and being satisfied with himself for years after. But Peter Claver did more than to go among them, to perform the necessary medical tasks, and then to leave in a cold sweat of relief. He was eager to go among them. To prove it, he did for them what no humanitarian would ever do. He touched them. He kissed them. He gave them back their dignity as human beings. His actions said, "You do not disgust me. You delight me, you are valuable to me, you need not be embarrassed in front of me. You are my brothers."

He did not run away from the plague. We run away from suffering as if it were the plague.

The pursuit of happiness

Father Claver made himself a slave in more ways than one. He placed an African in authority over him, and obeyed his decisions. He would awake in the middle of the night to hear confessions for eight hours, saying Mass in the morning and then Mass again at noon, before taking a drink of water. If one of the Africans was so ill he made the others nauseous, Father Claver lodged him in his own room, giving him his bed while he slept on the floor. People say of a generous man that he would give you the shirt off his back. But Claver would use his own robe to veil the sickest from the sight and smell of others; or let them use it as a pillow, or a cushion to sit on.

Sinners too are lepers. They too need the touch of love.

So I will end this essay with a story. There was a Spaniard who was sentenced to a horrible death for counterfeiting. Father Claver ministered to him in his cell. On the day of the hanging the rope broke, twice, and each time Claver was there to hold the man in his arms. The second time it broke, it must have done its job first, because the man gasped out his last breath while the priest was holding him.

It was that man, not Father Claver, who had written in his prayer book the night before, 'This book was owned by the happiest man in the world."

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Anthony Esolen. "How the Church Has Changed the World: "Slave of the Ethiopian Slaves." Magnificat (September, 2017).

Anthony Esolen. "How the Church Has Changed the World: "Slave of the Ethiopian Slaves." Magnificat (September, 2017).

Join the worldwide Magnificat family by subscribing now: Your prayer life will never be the same!

To read Professor Esolen's work each month in Magnificat, along with daily Mass texts, other fine essays, art commentaries, meditations, and daily prayers inspired by the Liturgy of the Hours, visit www.magnificat.com to subscribe or to request a complimentary copy.

The Author

Anthony Esolen is writer-in-residence at Magdalen College of the Liberal Arts and serves on the Catholic Resource Education Center's advisory board. His newest book is "No Apologies: Why Civilization Depends on the Strength of Men." You can read his new Substack magazine at Word and Song, which in addition to free content will have podcasts and poetry readings for subscribers.

Copyright © 2017 Magnificat