Should a Widowed Mother Aged Thirteen be a Saint?

- PAUL JOHNSON

Someone should write the life of Margaret Beaufort, as an example of how a woman of strong beliefs can survive a traumatic childhood and become a credit and exemplar to society. She ought indeed to be canonised, and I commend her cause to the present Pope, who also loves good Christian academics.

|

|

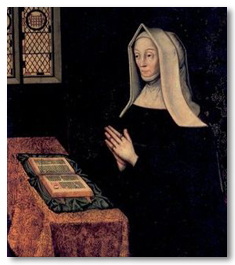

Margaret Beaufort

1443-1509 |

When is too old? When too young? Almost every day I hear a story of someone, at the height of his power and energy, being compulsorily retired at 60. Or there is a fuss because a girl wants to get married at 15. I recall that Lydia, youngest of the Bennet girls in Pride and Prejudice, was 15 when she ran off with the miscreant Wickham. She prided herself on the fact that she was taller than her siblings and was obviously precocious. When it came to the point the problem was not her age but getting Wickham to marry her. An underage girl is a moveable feast.

I have been reading about the fascinating case of Margaret Beaufort (1443-1509), who might fairly be described as the founder of the Tudor dynasty. She was both the beneficiary and the victim of outrageous fortune. She was, besides being a considerable heiress, the great-great-granddaughter of Edward III, and thus had a title to the throne. Indeed, she might have become queen regnant herself, and a very fine monarch she would have made. As it was, her father died when she was not yet two, and she was thus a valuable ward, passed from hand to hand among the great. While an infant, she was nominally married, for financial reasons, to John de la Pole, heir to the first Duke of Suffolk, though this required a papal bull to be valid, as they were within the prohibited degrees of relationship. This marriage was dissolved, again (I think) for financial reasons.

When she was nine, she was put in the custody of Edmund Tudor, Earl of Richmond, and his brother Jasper, who also got possession of her deceased father's lands. Edmund decided to marry her, and did so, in 1455, when she was either 12 or 13. This marriage was consummated, for she became pregnant. About three months before the child was born, her husband died. On 28 January 1456, Margaret was delivered of the future Henry VII. She was still only 13. An unprotected single mother of 13, and an heiress too, was a tempting target, and Margaret was married twice more, the second time to Lord Stanley, later Earl of Derby. At various times she was under house arrest. She was proscribed by Parliament and had her lands confiscated under Richard III, and I suppose was lucky not to have her head chopped off by him. Her son, an outlaw, was abroad. But all ended well when he won the Battle of Bosworth in 1485, being joined in the course of it by her then husband, Stanley, whose desertion of Richard III helped to decide the outcome. Richard was killed, and her son became king as Henry VII, by rights of battle to some extent but chiefly by descent through her.

Margaret's descendants, the Tudor monarchs, were a remarkable collection by any standards. Henry VII effectively ended the Wars of the Roses and gave England the stability and financial probity it badly needed. Henry VIII was the cruellest of England's rulers, and has been called "the English Stalin". But he set his mark on a vast range of national activities and institutions, from the Navy to music, and from religion to science. His brilliant son Edward died of TB before he could rule, and one of his daughters, Mary, made a disastrous foreign marriage which ruined her. But the other daughter, Elizabeth I, redeemed all by becoming perhaps the greatest of all English rulers.

Elizabeth had a lot in common with her great-grandmother Margaret. We do not know how deeply Margaret concurred in her first unconsummated and dissolved marriage, but to be married again at 12 and then to become a mother and a widow at 13 are chastening experiences, and no joke is intended. The two further marriages which followed may have been involuntary -- we do not know. What we do know is that Margaret, far from being psychologically shattered by her early experiences, matured to become a woman of exceptional qualities and real achievements.

Not that Margaret was pushy, on the contrary. Once her son became king, she made a point of not trying to influence him, precisely because he owed his title to her: she was a woman of tact and sensitivity. His letters to her show that he consulted her on matters of court procedure, and on episcopal appointments, for she had already acquired a reputation for piety and a wide acquaintance among the clergy. The king and parliament made many grants to her, for her lifetime, of lands and manors, and she devoted almost all her considerable income to charity, living simply at her manor of Woking in Surrey. As Stow said, "It would fill a volume to recount her good deeds."

Her most significant personal act was to appoint that outstanding Cambridge figure John Fisher to be her personal confessor, in 1497. The same year, he became Master of his college, Michaelhouse. He had already been senior proctor of the university, and with the Queen Mother's support he was the leading force in the revival of Cambridge scholarship and academic drive which made it, in the 16th century, the best university in the world.

After consulting with Fisher, she founded, at both Oxford and Cambridge, what became known as the Lady Margaret Professorship of Divinity. This was in 1502 and Fisher, at her request, became the first occupant of the Cambridge chair, until the King, after persuading his mother to agree to the move, made Fisher Bishop of Rochester. Her choice as his successor in the chair was Erasmus. By zeal and piety, Fisher was the outstanding member of the bishops' bench until Margaret's grandson, the evil Henry VIII, had him executed in 1535. But Fisher, in addition to his episcopal duties, remained a power in Cambridge, being elected Chancellor in 1504, and thereafter annually until given the unusual distinction of election for life. The next year, Margaret founded Christ's College, something which Henry VI had intended but never completed. She was asked by an Oxford group to refound St Frideswide's as an immense college, a work later carried out by Wolsey. Instead she turned to Cambridge again, and laid out vast sums to transform the corrupt monastic house of St John's into St John's College, a project realised just before her death. Altogether, she must share with Fisher the credit for remaking Cambridge, where she is still known as "the Lady Margaret". Fisher, appropriately, preached her funeral sermon:

All England for her death has cause of weeping. The poor creatures that were wont to receive her alms, to whom she was always piteous and merciful; the students of both universities, to whom she was a mother; all the learned men of England, to whom she was a very patroness; all the virtuous and devout persons, to whom she was as a loving sister; all the good and religious men and women, whom she so often was wont to visit and comfort; all good priests and clerks, to whom she was a true defender; all the noble men and women, to whom she was a mirror and exemplar of honour; all the common people of this realm, for whom she was, in their causes, a common mediatrix and took right great displeasure to them; and generally the whole realm hath cause to complain and to mourn her death.

I have little doubt that this eulogy was well merited. She was motivated throughout her life by strong religious impulses. Having discharged her marital duties to her last husband Lord Derby, she obtained permission to leave his side and take religious vows: she was already a member of five religious houses for women, though she died at her own manor. Someone should write her life as an example of how a woman of strong beliefs can survive a traumatic childhood and become a credit and exemplar to society. She ought indeed to be canonised, and I commend her cause to the present Pope, who also loves good Christian academics.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Paul Johnson. "Should a widowed mother aged thirteen be a saint?" The Spectator (September 10, 2008).

This article is from Paul Johnson's "And another thing" column for The Spectator and is reprinted with permission of the author.

The Author