Making the Church Matter in Quebec

- REV. RAYMOND J. DE SOUZA

Last week Cardinal Marc Ouellet, Archbishop of Quebec City, made front-page news across the country with his open letter asking forgiveness for the sins of the past.

|

|

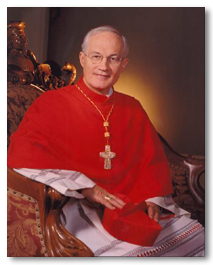

His Eminence Marc Cardinal Ouellet

|

Yesterday in this space, my colleague George Jonas devoted his column to that apology. And in Quebec, the Cardinal’s intervention dominated the news. The open letter of last week caps a year for Cardinal Ouellet in which something extraordinary has become ordinary again. The Archbishop of Quebec is once again a public figure of consequence.

For some time now, the bishops of Quebec have been at the margins of public life. Often they were not even offered the courtesy of being denounced; they were simply ignored. Which was altogether strange, because in the last several decades the local Catholic bishop has emerged in a variety of situations as the most prominent, if not singular, public religious voice. In the English-speaking world, the archbishops of Westminster (London), New York, Sydney and Toronto have assumed that mantle, a rather startling turn of events in cities where not so long ago Catholics were considered second-class citizens. In places as different as the Philippines, Mexico, Poland, Hong Kong, Kenya and Zimbabwe, Catholic bishops have taken a central role in public debates. Yet in Quebec, the Catholic voice has been muted.

In January, then Parti Québéçois leader André Boisclair called for the removal of the crucifix that hangs in the National Assembly. The usual script calls for various religious groups to object meekly, and then for the crucifix to be moved to a heritage room in some obscure wing of the building. Cardinal Ouellet tried a different line, opposed the proposal vigorously and won the argument. This month, Boisclair resigned from the National Assembly. The crucifix is still there.

Then Cardinal Ouellet opposed the provincial government’s plan to remove religious instruction from the public schools and to replace it with a survey course of world religions. Long accustomed to the Church in Quebec adjusting itself to ever-increasing secularization, the Cardinal’s robust objections at least sparked a debate.

His boldest intervention came before Quebec’s “reasonable accommodations” commission in October. Observing that “secular fundamentalists” had dominated Quebec life since the Quiet Revolution, he argued that this was a historical rupture: “Quebec society has rested for 400 years on two pillars: French culture and the Catholic religion, which form the base that enables it to integrate other elements of its current pluralist identity.”

“A people whose identity has been strongly configured for centuries by the Catholic faith cannot from one day to the next (a few decades are short in the life of a people) empty itself of substance without resulting in serious consequences at all levels,” Ouellet argued. “We must relearn that respect for religion which has shaped the identity of the people and respect for all religions without yielding to pressure from the secular fundamentalists who clamour for the exclusion of religion from public life.”

Similar things are said routinely by Catholic leaders in Munich, Madrid and Milan, but the reaction from the “secular fundamentalists” in Montreal was fierce. So fierce, indeed, that it could not have been the substance alone of Cardinal Ouellet’s remarks which provoked such a response; it was the very fact that he was making them. This bishop had forgotten his place. His appearance before the commission was styled as a call for a return to the Dark Ages, which in Quebec does not mean the first millennium, but the 1950s — la Grande Noirceur, the “great darkness” of the Duplessis era.

Hence the open letter of last week. Cardinal Ouellet’s request for forgiveness was a way of saying that he did not defend what should not be defended in the Church’s past. His argument is that Quebec culture has been shaped by the Catholic faith, for good or ill. That he believes that it is for the good does not mean he is blind to the ill.

The public emergence of Cardinal Ouellet and the visceral reactions against his interventions are themselves part of the same identity crisis which has generated the debate over reasonable accommodations. Since the Quiet Revolution, it has been accepted that to be a modern Quebecer meant relegating — often with disdain — religion to the purely private sphere. When a few Muslims declined to live as deracinated secularists, the whole province was plunged into the current melodrama. Similarly, the emergence of the Cardinal is something both novel, and to many, threatening.

By no means should Cardinal Ouellet’s influence be overstated. He is almost always playing defence. But the fact that he is even on the ice, refusing to be confined to the penalty box, is remarkable, and welcome.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Father Raymond J. de Souza, "Making the Church matter in Quebec." National Post, (Canada) November 29, 2007.

Reprinted with permission of the National Post and Fr. de Souza.

The Author

Father Raymond J. de Souza is chaplain to Newman House, the Roman Catholic mission at Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario. He is the Editor-in-Chief of Convivium and a Cardus senior fellow, in addition to writing for the National Post and The Catholic Register. Father de Souza's web site is here. Father de Souza is on the advisory board of the Catholic Education Resource Center.

Father Raymond J. de Souza is chaplain to Newman House, the Roman Catholic mission at Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario. He is the Editor-in-Chief of Convivium and a Cardus senior fellow, in addition to writing for the National Post and The Catholic Register. Father de Souza's web site is here. Father de Souza is on the advisory board of the Catholic Education Resource Center.