Hidden in the Mother's Womb

- ANTHONY ESOLEN

The priest looked about this strange and beautiful land.

Join the worldwide Magnificat family by subscribing now: Your prayer life will never be the same!

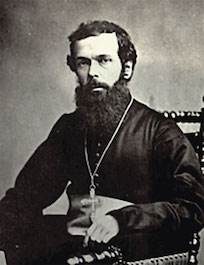

Father Bernard Petitjean

Father Bernard Petitjean1829-1884

Mountains rose up on three sides, with the harbor in front, and he could hear the rush of a swift stream nearby, coursing down to the bay.

"This is a good place for flowers," he said to his fellow, as they began to clear away some ground in front of the church they had just built, when suddenly they noticed several men and women, standing in front of the door, looking.

An old man approached them, a peasant as it appeared, his countenance creased with the sun, and toil, and age.

Trouble, thought the priest, but he smiled at the old man, and motioned for him to come nearer.

The old man did, holding his cap in his hand, and making a small bow. He stared at the cross lying upon the priest's chest. "Kirishitani!" he said.

Now it was the priest's turn to stare in amazement. "Hai, Kirishitani!" — "Yes, we are Christians!"

The old man fell to his knees, and began to pray, in a kind of pidgin of Latin and his native tongue: Pataro nosataru kyu eso in chelo.

"Dear Lord," said the priest, "is it possible?" And he turned to the old man and spoke in Japanese. "Where did you learn that prayer, my good man?"

"From my father, and he learned it from his father."

A woman came up. "Where is the Lady?" she said.

It was like coming upon a city lost for more than two hundred years.

"Saint Francis Xavier," said the priest, "you planted the seeds well!"

The priest was Father Bernard Petitjean. The place was Nagasaki, 1865. During all that time, thousands of Christians in Nagasaki, without the benefit of books, priests, schools, and the sacraments, kept what they could recall of the Faith, in secret, against the cruel enmity of the ruling shogunate. With all our liberties we should do so well.

A slender thread

The Japanese were suspicious of outsiders, and after Francis Xavier and his brothers had established flourishing missions in Japan, the Emperor Hideyoshi came to believe, from an idle word dropped by a Spanish sailor, that the Christians whom he had once treated tolerably well were the advance troops of an invasion. Persecutions followed, whose cruelty was unlike anything even the Romans could come up with. In 1597, several decades after the first arrival of the missionaries, twenty-six men, eighteen of them Japanese, were crucified at Nagasaki, after a forced march of four hundred miles. One of them was a twelve-year-old boy. In the ensuing months, around 137 Jesuit churches were destroyed, along with a seminary and a college.

Think of that for a moment. Francis Xavier came to Japan in 1549. With everything against them — the touchiness of the ruling class, the foreign language, the customs many centuries old, a native system of religion that combined the Buddha with Confucius with Shinto ancestor worship and pantheism — they had, in less than fifty years, built more than two churches every year, not to mention their other establishments for education and the care of the poor. With so little, so quickly, they did so much!

Nor was it a mere superficial conversion to the Faith. We can tell, because in 1637 the people of Nagasaki rose up one last time in revolt against the nobility who wanted to destroy all traces of the religion, but they were crushed. The Japanese did not, that time, mind the assistance of foreigners to put down the Christians, because Dutch artillery played its signal part in the rout. Such is the fruit when Christians are not at one.

That was after the shoguns had set the policy of "trampling the crucifix." The idea was simple. You rounded up everybody suspected of being a Christian, and you placed a crucifix before them, ordering them to trample upon it. It's something that Western man does all the time. But many Japanese people did not. They were crucified instead — or thrown alive into a volcanic spring.

And even after the terrible punishments and the apparently final defeat, with nothing to gain and everything to lose, so many Christians of Nagasaki held on, held on by the slender thread of prayer, strong as steel.

After war, work

Let's advance the years. It's October 1918, one century ago. The good Pope Benedict XV, exhausted by his many failed attempts to avert the madness and destruction visited upon Europe by World War I, has just issued his encyclical Maximum illud. It is an utterly beautiful document, not bearing the slightest trace of political jargon. Benedict was embroiled in the political evils of his time, yet Maximum illud is quite literally timeless. He adjures the missionaries to be men of "humility, obedience, chastity, and especially of piety, prayer and constant union with God," praying for the souls of the lost. He reminds them of the words of Saint Paul, that the chosen of God should put on "the bowels of mercy, benignity, humility, modesty, patience." By such virtues, says the Pope, "truth finds an easy and direct access to souls," for not even stubborn wills can resist them.

Benedict doesn't pretend that the uncatechized will be all sweetness and light. It does not matter, for the true missionary must be like Jesus, "burning with charity" and "ready to number among the sons of God the most backward Gentiles." He — or she, since Benedict calls upon women too — "is neither irritated by their roughness nor roused by their moral perversity; he neither despises nor scorns them; he does not treat them harshly or bitterly, but he will strive to attract them by all the good offices of Christian charity, to draw them all into the embrace of Christ, the good Shepherd."

These are words we need to take to heart, because we now live as Father Petitjean did, in partibus infidelium, among people with little faith, confused love, and no hope at all. We say, "I would have been kindly to those Japanese!" But can we do what is even harder, and be kindly to the addled agnostic next door?

So the missions in Japan continued, bearing a rich bounty. Nor should we think that it was all Europeans — not by a long stretch. For Benedict urged that the missionaries train up native men to be priests: "Linked to his compatriots as he is by the bonds of origin, character, feelings and inclinations, the indigenous priest possesses exceptional opportunities for introducing the faith to their minds, and is endowed with powers of persuasion far superior to those of any other man." For Christ speaks in Japanese, too.

More war, and more work

It is twenty-seven years later, August 9, 1945. The Second World War has seen the best and the worst of the Japanese people: their courage, their cruelty, their devotion to the emperor, their stubborn imperialism, their love of country, their lack of any good higher than their country to love. These are common ailments in the glorious and shameful story of mankind.

Three days before, the United States dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima. The Japanese did not surrender. Then the Russians abrogated their truce with Japan and declared war. Meanwhile, the Americans wanted to wait no more.

Nagasaki was both the home for the most vibrant communities of Catholics in Japan, and a port for repairing, arming, and refueling ships. So they were made the choice for the next bomb. It came, and it incinerated — men, women, children, soldiers, civilians, a few Allied prisoners of war, hospitals, roads, houses, and churches, the Catholic churches.

But there were survivors of the massacre. One was a Catholic woman, carrying a child in her womb. The child was a boy, and grew up in the Faith. He is Joseph Takami, a Sulpician priest and the Archbishop of Nagasaki. Bishop Takami has put forth the cause for sainthood for a brave samurai Catholic, Takayama Ukon, who with his family endured the persecution under Hideyoshi, so long ago. So the world comes full circle. And we may pray that the courage of the Japanese martyrs, the endurance of the Hidden Christians, the tears of joy that Father Petitjean shed, and the prayers of Japanese Catholics who must battle through a time of wealth, apathy, spiritual dryness, and all the other diseases coming out of the West, will once again cause the Faith to bloom in that ancient and noble land.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Anthony Esolen. "How the Church Has Changed the World: Hidden in the Mother's Womb." Magnificat (October, 2019).

Anthony Esolen. "How the Church Has Changed the World: Hidden in the Mother's Womb." Magnificat (October, 2019).

Join the worldwide Magnificat family by subscribing now: Your prayer life will never be the same!

To read Professor Esolen's work each month in Magnificat, along with daily Mass texts, other fine essays, art commentaries, meditations, and daily prayers inspired by the Liturgy of the Hours, visit www.magnificat.com to subscribe or to request a complimentary copy.

The Author

Anthony Esolen is writer-in-residence at Magdalen College of the Liberal Arts and serves on the Catholic Resource Education Center's advisory board. His newest book is "No Apologies: Why Civilization Depends on the Strength of Men." You can read his new Substack magazine at Word and Song, which in addition to free content will have podcasts and poetry readings for subscribers.

Copyright © 2019 Magnificat