Heeding the Call

- CHARLES LEWIS

The founder of L'Arche has spent nearly a lifetime championing the severely disabled.

|

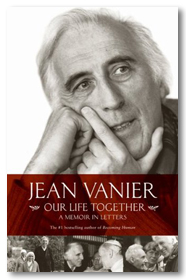

Not long into Jean Vanier's collection of letters, which serves as the closest thing to a memoir we are likely to get of his remarkable life, it is clear we are in the company of a driven man, someone perhaps mad with an enormous Christ complex, dragging his readers along on an exhausting journey through poverty, misery and disease — and also to places of small joy and hope.

Vanier is the founder of L'Arche, a worldwide movement of modest numbers but larger spiritual impact, which creates homes for the mentally and physically disabled. These are people who might otherwise have languished in institutions or lived out their lives begging in the streets. Some who live in L'Arche are capable of holding jobs and taking on small responsibilities; others have handicaps so severe that they need almost non-stop attention.

These letters, which were originally intended as newsletters from the boss, were the means by which Vanier communicated the bigger picture to his growing network of L'Arche homes. They were never addressed to individuals; the salutation was always "Dear Friends." It was how he told about his travels and his encounters with society's most rejected.

The L'Arche movement started in France in August, 1964, when Vanier opened a home for two developmentally handicapped men, Raphael Simi and Philippe Seux, who had been locked up in a "dismal institution" when their parents died. Previously, after leaving the navy, Vanier had contemplated becoming a priest. He ran a Catholic retreat centre in France and ended up teaching at St. Michael's College at the University of Toronto around the time his father, Georges, was governor-general of Canada (1959-67).

Back in France, he visited psychiatric institutions to observe how society dealt with its discards. Then, with the help of family and friends, he bought a "rather dilapidated house" in the village of Trosly-Breuil, an hour north of Paris.

"When I welcomed Raphael and Philippe, there wasn't a specific or rational reason — it just seemed obvious," he writes in Our Life Together: A Memoir In Letters. "They were crying out for relationships and I could provide it. Practically everything I did with L'Arche was intuitive, based on the sense that this is what should be done."

But, as the letters reveal, L'Arche was always far more than a shelter. Rather, as Vanier writes, it was the starting point for an all-encompassing philosophy rooted in the Gospels of the New Testament.

"The way of the Gospel lived in L'Arche ? means living with the poor, creating community with them, listening to their cry and letting ourselves be transformed by them. This living with reveals very quickly the egoism, anguish and fears in us all. For the poor call us continually to go farther in our love and in the bonds that unite us. At the same time, their call and these bonds of friendship form and transform our hearts, encouraging us to give ourselves more fully and to live the Beatitudes of Jesus."

Later, he puts it even more succinctly: "If we all put ourselves more fully at the service of the weak, then we would walk more surely toward peace and unity. In our divided, broken world, it is they who call us to unity."

In these letters, which span more than 40 years, Vanier's travels and missionary zeal build in intensity. There he is in Calcutta among the most rejected of the rejected, then he's in the slums of Cleveland testifying about Jesus, then he's visiting a prison in Nigeria, consoling condemned men with the story of the good thief, the one Jesus promised to welcome into Heaven after his death and resurrection.

There he is in Lebanon, Brazil, Haiti and Ivory Coast, spreading his message of love and reconciliation like a mod-ern-day St. Paul, though if St. Paul had had jet travel at his disposal, it is by no means certain he could have kept up with Vanier's punishing pace or his level of enthusiasm. Sometimes Vanier is caught up in current events, giving a homily for Oscar Romero, who was assassinated by a right-wing death squad in San Salvador, or popping up in Israel at the start of the Intifada.

For most of us, the sight of just one of the desperate corners of the world Vanier describes — let alone the scores he witnessed and writes about here — would leave behind far too many nightmares and a lingering taint of guilt. In a letter from Honduras in 1975, he recalls a visit to a mental asylum: "Two-hundred-and-fifty men and women living in abominable conditions. Some of them were totally naked, a few were locked up in solitary confinement; the roof, the beds, everything was broken. There was a smell of urine, and rats all over the place. In one corner there were twenty empty coffins stacked up waiting for future clients. The personnel were watching television. I don't blame them!"

Vanier makes no reference to lovers, wives, children or close friends gathered in cafes in moments of abandonment. There is a lack of intimacy in the way that most of us think about intimacy, that is, in terms of family, friends and work. Instead, what sustains Vanier is an intimacy so raw that only someone hovering in the neighbourhood of saints could abide it. Many of the images in Our Life Together are disturbing. Yet, in every grim description of painful misfortune, Vanier wants us to see a divine light.

"One Sunday, with Mother Teresa, we visited one of the hospitals she founded for lepers: about one hundred people, their faces, hands and feet eaten up by the illness, but there was a radiant joy in their beings. They sang and danced. It is strange how beautiful the face of a leper can be even though humanly it is so disfigured. It is the light and peace in the eyes."

Later, speaking to Mother Teresa's novice and sisters, he reminds them of exactly what they are doing when they say they are following Jesus. "It is easy to speak about Jesus, Jesus in the poor; but to go out into the streets and come face to face with people in rags, people with empty stomachs, is another matter. Pray that I may learn how to live with the poor and never let my heart be closed up in my own comfort, well-being or flattery. Pray that Jesus may keep me continually in anguish in front of the poor." His prayers were answered.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Charles Lewis "Vanier: 'Heeding the call." National Post, (Canada) November 3, 2007.

Reprinted with permission of the National Post. Charles Lewis writes for the National Post.

The Author

Charles Lewis writes from Toronto.

Copyright © 2007 National Post