"Good Sport"

- DONALD DEMARCO

"If St. Christopher could protect travelers," thought the enterprising Miss Kearns, "perhaps he could ensure the safe passage of Gil Hodges around the bases."

|

|

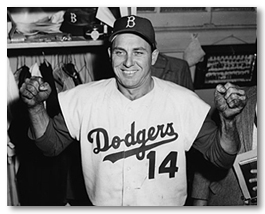

Gil Hodges

|

Doris Kearns Goodwin lives in Concord, Massachusetts, not far from the Old North Bridge. It was from that "rude" construction, in Ralph Waldo Emerson’s deathless words, that "the embattled farmers stood, / And fired the shot heard round the world." Goodwin is a noted historian and Pulitzer Prize-winning author whose books on the Fitzgeralds and the Kennedys, Lyndon Johnson, and Franklin D. Roosevelt have brought her great acclaim.

Yet, when she takes visitors to that historic site, she thinks not of the epic moment that launched the American revolution, but of Bobby Thomson’s shot into the left-field seats at the Polo Grounds that ended the Dodgers’ pennant hopes in 1951.

Her memoirs, Wait Till Next Year (1997), reveal the eternal child in her, the one whose formative years paralleled the career of her idol, Jackie Robinson. Baseball was her passion long before she knew anything about the impact that American presidents have had on modern history.

While preparing for Confirmation, a youthful and impressionable Doris Kearns won a Catholic catechism contest. Her passionately sought prize was a St. Christopher medal that had been blessed by the pope.

She had immediate and important plans for her newly acquired trophy. It was to cure the Brooklyn Dodgers first baseman, Gil Hodges, of a prolonged batting slump. "If St. Christopher could protect travelers," thought the enterprising Miss Kearns, "perhaps he could ensure the safe passage of Gil Hodges around the bases."

The time was propitious. The slumping Hodges was soon appearing at Wolf ’s Sport Shop on nearby Sunrise Highway to sign autographs. Kearns’s plan was to present him with her holy icon and thereby break him out of his hitting drought. She finagled her mother into driving her to the scene, and after waiting in line until she was face-to-face with her wilting hero, she handed him her unusual bromide along with a carefully rehearsed monologue: "This medal has been blessed by the pope and I had won it in a catechism contest when I knew the seventh deadly sin was gluttony, and I thought St. Christopher would watch over [your] swing so that [you] could return home safely each time [you] went to bat and would make me feel good and would make Dodger fans all over the world feel great."

She concluded her rambling, but charming, disquisition amidst good-natured laughter from those standing around her. Hodges, however, responded with solemnity and graciousness. He confided that he, too, once had a St. Christopher medal blessed by the pope. But he had seen fit to give it to his father, a coal miner in Indiana. The senior Mr. Hodges had broken his back, lost an eye, and severed three toes in a series of mining accidents. The towering first baseman said he thought that his dad needed the medal more than he did. He was thrilled, he said, to receive a medal of his own. Then, he reached out in a gesture of gratitude and enveloped the delicate hand of Miss Kearns in a massive palm that was several times the size of her own. Miraculously (or otherwise), Hodges regained his batting eye virtually overnight.

A good sport retains his civility and humanity even in the midst of losing—indeed, even in the midst of an extended batting slump. He does not take out his disappointments on innocent bystanders. For those who think that winning is everything, good sportsmanship and graciousness are neither virtues nor options.

The newspapers bring to our attention on a regular basis how serenely indifferent the "baseball gods" can be to their "adoring fans." Some will never, under any circumstances, descend from the clouds long enough even to sign an autograph. Gil Hodges was a welcomed and memorable exception.

Winning is hardly "everything," as the saying goes. Retaining a courteous comportment with one’s neighbor is, on a human scale, far more important than outscoring him. Winning on the plane of the emotions is nobler than winning on the playing field. Our culture identifies sports so closely with life that it unthinkingly categorizes people as either "winners" or "losers." Yet, both the "winners" and "losers" remain human.

Good sportsmanship and civic graciousness constitute a light that shines more brightly than stardom because they shine from the heart. Doris Kearns felt the warmth from that light when she was a young girl, and it has continued to glow in her own heart ever since.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

DeMarco, Donald. "Good Sport." Lay Witness (March/April 2007): 36-37.

Reprinted with permission of Lay Witness.

Lay Witness is the flagship publication of Catholics United for the Faith. Featuring articles written by leaders in the Catholic Church, each issue of Lay Witness keeps you informed on current events in the Church, the Holy Father's intentions for the month, and provides formation through biblical and catechetical articles with real-life applications for everyday Catholics.

The Author