Bishops have denied communion before

- TIM TOWNSEND

In November 2003, Raymond Burke, then the bishop of LaCrosse, Wis., instructed priests in his diocese to deny Communion to three politicians unless they publicly recanted their pro-abortion rights positions. Since then, Burke's supporters have increasingly pointed to what they see as parallels with another case, and another moral hero, from 40 years ago.

|

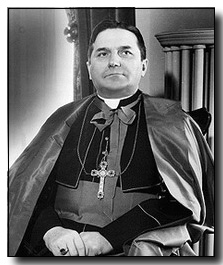

Archbishop

Joseph Francis Rummel (1876-1964) |

In the wake of the United States Supreme Court's 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling, Joseph Francis Rummel, Archbishop of New Orleans, began planning the integration of the archdiocese's schools. It would take eight years, several court battles and the excommunication of three prominent Catholic political figures for Rummel to achieve his goal.

As Americans debate the public and private responsibilities of Catholic politicians in this election year, the story of Archbishop Rummel's decision to use the serious punishment of excommunication with members of his flock is returning to the national conscience. This time, the story is being wielded by conservative Catholic groups that would like to portray Burke's stance on politicians, Communion and abortion as the moral equivalent of Rummel's stand against racism.

Rummel was concerned about racial integration even before Brown v. Board of Education was handed down. In 1953, a year before Brown, he wrote a pastoral letter called "Blessed Are the Peacemakers" that ended segregation in archdiocesan parishes.

In another pastoral letter in February of 1956, he wrote that "compulsory racial segregation is morally wrong and sinful," according to Dr. Charles E. Nolan, the archdiocese archivist. The following month, lawyer and segregationist Emile Wagner founded the Association of Catholic Laymen in response to Rummel's statements about integrating New Orleans schools. Wagner called integration "an unproven principle and the plot of communists," according to New Orleans archdiocese archives.

Rummel responded by calling the group "unnecessary" and "scandalous" and in an April letter to the group's 30 board members, threatened each with excommunication. In May, Wagner and his group backed down and disbanded, but later sent a letter to Pope Pius XII, appealing their ability to organize without threat of excommunication.

As the 1950s wore on, and much of the South ignored Brown, Rummel gradually began planning the integration of New Orleans Catholic schools.

"Archbishop Rummel knew what he was up against in New Orleans politics, and he knew he had to lay the groundwork slowly," said the Rev. William F. Maestri, a spokesman for the archdiocese.

In 1960, legislators in Baton Rouge sent letters to the archbishop threatening the withdrawal of aid to, and tax-exempt status of, New Orleans Catholic schools should Rummel persist in his attempts to integrate them.

In March of 1962, Rummel announced a plan to integrate all Catholic schools in New Orleans the following school year, but he again met with strong resistance from segregationist Catholics. Judge Leander Perez, president of the Plaquemines parish, was one such Catholic. (Louisiana is divided into parishes rather than counties.)

"Perez was like the Richard Daley of Plaquemines and St. Bernard parishes," said Maestri. "He was an old-style political boss."

At a public rally the day after Rummel's announcement, Perez told an audience that no matter what the archbishop said, Catholic schools in Plaquemines would not integrate. He urged them to pull their children from parochial schools, and withhold contributions to the archdiocese.

After several more public, heated exchanges with Perez, Rummel again sent letters to dissenting Catholic segregationists, in which he said they "promoted flagrant disobedience," and that unless they backed down, they would be excommunicated. Many again relented, but Perez and two others did not. Rummel waited two weeks, and when he didn't hear from the final three, he publicly excommunicated them for their "flagrant disregard" for his "fatherly council."

Maestri said Rummel's actions were not political, but moral. "For him this was a fundamental moral issue," he said. "He was clearly motivated by one thing: to do what was just and right."

St. Louis's own archbishop, Cardinal Joseph Elmer Ritter, issued similar decrees seven years before the Brown decision, in 1947 when he became the first person to integrate an entire school system in a former slave state. When he learned some Catholics were threatening legal action to stop his integration plan, Ritter sent a letter to be read at every Sunday Mass in the archdiocese explaining to Catholics that anyone using the courts to try to stop integration of Catholic schools would face excommunication.

Excommunication, according to the Harper Collins Encyclopedia of Catholicism is "the penalty in canon law that partially excludes a Catholic from the life of the Church. Excommunication does not expel a person from the Church, but it does distance one from the Christian community." The result of such a penalty is that the excommunicated person is "not allowed to receive or administer the sacraments."

Whether or not a person who is denied the sacrament of Communion has been excommunicated by the church is debated. Since the central penalty involved with excommunication is denial of the sacraments, some scholars argue that when the most important sacrament there is the Eucharist is denied, that person effectively, if not technically, is excommunicated.

Denial of Communion is "not really excommunication, but does amount to virtual excommunication," said the Rev. Thomas Rausch, a Jesuit professor of Catholic theology at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles. Lawrence Cunningham, professor of theology at the University of Notre Dame, said denial of Communion is "the functional equivalent of excommunicating someone."

|

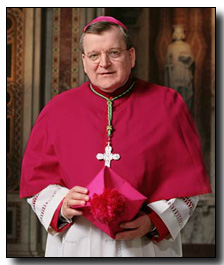

Archbishop

Raymond L. Burke |

In a recent article in America, a Jesuit magazine, Burke argued that the church law he cites to explain his intended denial of Communion to politicians who support abortion rights (Canon 915) is not part of the law code that treats "ecclesiastical sanctions," or punishments, and therefore, could not possibly be called excommunication.

He points out that Canon 915 "requires that those who 'obstinately' persevere 'in manifest grave sin are not to be admitted to Holy Communion.'" Burke concedes in the article that the law code's "ecclesiastical sanctions may involve exclusion from the reception of holy Communion." But he notes that Canon 915 also "refers to an exclusion that is inherent in the nature itself of the sacrament of the holy Eucharist." In other words, while the denial of Communion may appear to be driven by Burke's reading of the law code, he maintains it is simply a natural extension of the rules associated with accepting the Eucharist in the first place.

Denial of Communion is "quite a distance from excommunication," Burke said in an interview. "That's why I make that distinction that (denial of Communion to a politician) is not part of the penal code of the church. Canon 915 deals with the state of someone who persists in an open, serious moral violation and so has gravely sinned. This means you can't receive communion, but it is not saying you are excommunicated. It's just saying you have broken, in a very serious way, your communion with God and with the church and therefore are not able to receive holy Communion."

Some conservative Catholic organizations have glimpsed parallels in the cases of Archbishops Rummel and Burke. They see two men who stood up, in the face of tremendous opposition, for a moral imperative. That both men were willing to use the sacrament of Communion to make their points is further proof for such groups that the two cases are similar.

"If you're looking at heroism and courage, there are lots of similarities between them," said Judie Brown, president of the American Life League, an anti-abortion group based in Washington.

Others believe that by taking a stand on the issue of Catholic politicians and Communion, Burke just as Rummel did in the 1960s is blazing a path for other, meeker, American bishops to follow.

"The rest of the bishops don't have the degree of courage exhibited by Archbishop Burke. He's going against the grain," said William Donohue, president of the conservative Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights. "He's saying, 'I have it in my authority to do what I think is right.'"

But more liberal Catholics challenge the extent of the parallel between the Rummel and Burke cases. They say they don't see any similarities between the Rummel case, in which politicians were actively defying the archbishop's authority within his own archdiocese, and the Burke case in which Catholic politicians who support abortion rights are not specifically challenging Burke himself on the abortion issue, but rather say they legislate for Catholics and non-Catholics alike.

"There are no convincing parallels between today's situation and the one in New Orleans more than 40 years ago," said the Rev. Richard P. McBrien, a liberal Catholic and professor of theology at Notre Dame University. "None of today's pro-choice politicians has openly opposed the Church's teaching on the morality of abortion nor defied any of the bishops' rights to articulate that teaching."

Others who feel some bishops' pronouncements on Catholic politicians and Communion are meant to play a role in national politics are more specific. "In new Orleans, those politicians held that segregation was good," said Robert McClory, a retired Northwestern University professor, and former board member of Call to Action, a liberal Catholic organization. "(Senator John) Kerry does not hold that abortion is good, but rather that he is against criminalizing it."

Even those who would like to draw similarities between the two cases point out differences. "Where the parallel begins to fall apart is in the moral seriousness of the issues," said Donohue. "Segregation is morally wrong, but when you're talking about the killing of a child, that's intrinsically evil. The more egregious offense is abortion, not segregation."

Burke himself sees similarities in the two cases, but also points out a big difference. "It was a question then, too, of a grave moral wrong," he said. "Archbishop Rummel, eventually excommunicated those who dissented openly, after admonition, from church's teaching. So there is a parallel."

Denial of Communion to Catholic politicians who support abortion rights, said Burke, "doesn't have to do with Canon 915, in the sense that the canon doesn't require that the person be excommunicated, but it could come to that."

Most experts say it was the public nature of the New Orleans politicians' active dissent from the archdiocese that forced Rummel to excommunicate them, and that in Burke's case such public and active dissent is missing from Catholic politicians' positions concerning abortion. But for the archbishop of St. Louis, a Catholic politician's dissent on abortion is a serious problem any way you look at it.

"Surely the two situations are not perfectly the same," said Burke. "There are differences. But if (abortion) is a grave moral evil, which surely it is, then a person who is taking public stands in favor of it, and even accepting recognition from groups that are promoting it, then it's dissent by whatever name you want to call it. Maybe it's less extravagant, but it is full-blown dissent."

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Tim Townsend. "Bishops have denied communion before." St. Louis Post-Dispatch (July 10, 2004).

This article reprinted with permission from the St. Louis Post-Dispatch .

The Author

Reporter Tim Townsend writes about religion for the Post-Dispatch. E-mail: ttownsend@post-dispatch.com Phone: 314-340-8221

Copyright © 2004 St. Louis Post-Dispatch