Beyond the River Kwai

- LT. ERIC LOMAX

As my London-bound train clicked over the rails that fall afternoon in 1989, my eyes were transfixed by a newspaper photo of an elderly Japanese. This was the man I had searched for the one who had brutally tortured me years before.

|

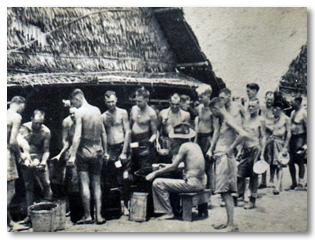

Approximately 100,000 Asian & 16,000 British died

during the construction of the Burma-Siam railway |

Those of us who have seen the riveting war film, The Bridge Over the River Kwai, know how terrible the prisoners of war were treated during the building of the infamous Burma-Siam railway. How could a survivor of that daily hell ever forgive what was done to him? Eric Lomax certainly could not — and his nightmares never ended. Until...

As my London-bound train clicked over the rails that fall afternoon in 1989, my eyes were transfixed by a newspaper photo of an elderly Japanese. This was the man I had searched for — the one who had brutally tortured me years before.

Back in 1942 I was a prisoner of war in a Japanese concentration camp. A 23-year-old lieutenant in charge of the signal section of the 5 th Field Regiment, Royal Artillery, I was captured with my unit at the fall of Singapore. Hundreds of thousands of British troops were herded into camps to starve, rot and die. Some of us worked as slave laborers on the infamous Burma-Siam railway depicted in the film The Bridge On the River Kwai. To get supplies to Burma, Japan decided to build a railroad across a forbidding range of spiky mountains, a route so terrible that British colonial engineers had rejected it. Working under the fierce tropical sun, we captives used picks, saws and axes to clear out bamboo and tropical hardwood day after day.

A group of us was sent to a prison camp where we assisted Japanese railroad mechanics and engineers doing repairs. We were famished for news of the outside world. Scrounging bits of silver paper, wire, aluminum and wax, we assembled a small radio set on which we could receive All India Radio from New Delhi. The radio gave us word of Allied victories in the Solomon Islands and Guadalcanal. The boost to our morale was tremendous.

We took the radio to our next camp, on the river Kwai. Here in snake-infested surroundings, in oppressive humidity and heat, we turned to it for hope. I drew a map of the area, which I kept hidden in a bamboo tube. At night I turned to my Bible. Reading Job, I echoed his prayer: “I am full of confusion; therefore see thou mine affliction; for it increasith” (Job 10:15,1 6).

In August 1943 our captors discovered our radio. Five of us suspects were forced to stand at attention for 12 hours. As we stood under the blazing sun with flies and insects feeding on our sweaty and itching skin, tongues swollen from thirst, I thought of Christ on the cross.

A squad of drunken guards began beating us one by one with heavy pickax shafts. We had to watch each 40-minute beating, hear bones crack and see blood stain the earth. When it was my turn the first blow shot scorching pain through me. Hundreds of blows followed. I felt as if I were plunging into an abyss and saw tremendous flashes of light. Boots crunched my face into the gravel; I heard my arms snap, my teeth break. In utter despair I could only cry out, “Jesus!”

Four other men were similarly beaten. Two of them died, and their bodies were flung into a latrine trench. The rest of us were thrown into bamboo cages about five feet long and two and a half feet wide. I’m more than six feet tall, so I couldn’t stretch out. Huddled and cramped, I held up my broken arms to prevent my weight from crushing the unset bones. Large red ants swarmed over me and I couldn’t sweep them away.

Five of us suspects were forced to stand at attention for 12 hours. As we stood under the blazing sun with flies and insects feeding on our sweaty and itching skin, tongues swollen from thirst, I thought of Christ on the cross. |

The next day I was dragged into a room for interrogation. At a table sat a small, almost delicate, young man with jet-black hair and a wide mouth. Next to him hunched a large, muscular NCO with a shaved head. The smaller man, who appeared to be in charge, introduced himself as an interpreter in his investigation of “wide-spread anti-Japanese activities.” As the NCO barked his accusations, the interpreter said my colleagues had made full confessions, that they knew about my part in using the radio and passing news on to others.

“Lomax, you will be killed whatever happens,” he said. “It will be to your advantage in the time remaining to tell the whole truth. You know how we deal with prisoners when we wish to be unpleasant.”

I began to hate them both. The interpreter’s voice grated on and on, giving me no rest. Even at night I was awakened and pulled into the room by the interpreter. For 18 hours a day I sat, balancing my broken arms on my thighs, forced to hear the same questions over and over.

In between grillings I lay in the cage in my own dirt. Mosquitoes swarmed over me. In my nightly delirium, I heard biblical words: “Behold, I stand at the door, and knock: if any man hear my voice, and open the door, I will come in to him.”

One morning I was taken into the room to see my railway map spread out on the table. A barrage of questions exploded: “Were you planning to escape? Name the others.” The interpreter’s frustration mounted as I remained silent.

I can’t remember what happened next. My fellow prisoners said my head was shoved into a big water-filled tub again and again. What I remember was being forced to lie on my back, tied down to a bench.

“Lomax, you will tell me . . .” spoke the smaller Japanese. With each question, the NCO struck my stomach, chest and arms with a heavy tree limb. “Lomax, you will tell.”

Then the NCO took a hose and pressed its full torrent into my nostrils and mouth, gagging me, filling my lungs and stomach. It was like drowning on dry land. When the hose was removed, the interpreter spoke into my ear while the NCO struck me. I had nothing to say. Again that shock of water rising inside me.

I don’t know how long they alternated the beatings and half drownings. Eventually we were transported to another camp, where we were forced to sit in cells cross-legged every day for 36 days, awaiting court-martial. In November 1943 I was sentenced to five years imprisonment and began a living death, wasting away to a walking skeleton.

When I was at the point of death, they would take me to the POW “hospital,” where I would regain consciousness. Then back to prison. Meanwhile, rumors began to spread. We heard the Nazis were nearly destroyed, Rangoon had been captured. In the summer of 1945 fellow prisoners whispered about a new type of bomb used on Japan. Then one day American B-29 bombers dropped food and medical packages. We were free!

But I was not. I continued suffering the emotional effects of my torture. I took up my life in England, got married, served in the military and the colonial service, but my nightmares never ended.

Finally, I reached a former British Army chaplain who had been in contact with former Japanese soldiers. He told me he had found the interpreter. His name was Nagase Takashi and he lived in the city of Kurashiki. |

I frightened Patti, my wife, by awakening screaming. Or I withdrew in cold silence. Psychiatric evaluation showed I suffered from wartime trauma, a kind of prolonged battle stress. I could not forget the Japanese who had hurt me. I wanted to harm them, in particular the hated interpreter with his mechanical voice, “Lomax, you will tell.”

I followed the news from Japan, noting that two camp commanders had been hanged for their part in my fellow prisoners’ murders. But there was no trace of my interpreter.

Finally, I reached a former British Army chaplain who had been in contact with former Japanese soldiers. He told me he had found the interpreter. His name was Nagase Takashi and he lived in the city of Kurashiki. He said Takashi had become active in charitable causes near Kanburi and had built a Buddhist temple of peace close to the railway as an atonement. I reacted with cold skepticism.

Then in October 1989, I renewed a friendship with a fellow POW, Jim Bradley, whom I visited in Midhurst, a village in Sussex. We had a pleasant time, and over breakfast, he gave me a photocopy of a recent article from the JapanTimes, an English-language paper published in Tokyo.

It was a story about Nagase Takashi, including his photo. All the way back to London on the train I studied the clipping, the old rancor rising in me. The photo depicted a slight, unsmiling man in a dark collarless shirt. The text told how the ailing 71-year-old had devoted his life to making up for the Japanese Army’s treatment of prisoners. It said he suffered terrible flashbacks of torturing a British POW who was accused of possessing a map.

I dropped the paper in my lap. He remembered me. A sense of triumph filled me. Now I knew where he lived. I wanted to see if his remorse was genuine. I wanted to see his sorrow. Some people suggested I forgive and forget. They mentioned Christ on the cross forgiving his tormentors. But how could I forgive after what I had been through?

My hate festered. Then in July 1991 a friend gave me a small paperback by Nagase called Crosses and Tigers, translated into English. In telling his wartime activities, Nagase described my torture. He said he shuddered every time he recalled it. He expressed his remorse and felt he had been forgiven.

Never, I thought. Patti was indignant. With my permission she wrote Nagase, telling how I had suffered. “How can you feel ‘forgiven,’ Mr. Nagase, if this particular prisoner of war has not yet forgiven you?”

More than a week later a tissue-thin envelope from Japan arrived. “Your letter has beaten me down,” Nagase wrote my wife, “reminding me of my dirty old days.” Patti had sent him a photo of me and Nagase observed, “He looks a healthy and tender gentleman, though I am not able to see the inside of his mind. Please tell him to live long until I can see him.”

Overcome with emotion, we spent some time talking quietly, two men now united. I felt peaceful and whole again. In the months to come, my nightmares seldom returned. |

Suddenly, as I read, my anger began to seep away. In its place rose compassion. I began to think the unthinkable: that I might meet Nagase face-to-face, without rancor.

My reply was brief and informal. It took a year to arrange our meeting. Patti and I flew to Bangkok and took a train to Kanburi, where Nagase and I would rendezvous at the old prison camp site on the river Kwai.

On a hot, sunny day I stood on a terrace by the bridge, watching my former adversary walk toward me. I had forgotten how small he was, a tiny man in a straw hat, loose kimono-like jacket and trousers.

He began a formal bow, his creased face agitated. I took his hand and said in Japanese, “Good morning, Mr. Nagase. How are you?”

He looked up, trembling, with tears in his eyes. “I am very, very sorry,” he said over and over.

I led him to the shade and we talked about our mutual experiences. It was obvious he had suffered much too. “I think I can die safely now,” he said. As we walked around the area where the prison camp once stood, we discovered much in common: books, teaching, an interest in history. But still my words of forgiveness would not come.

Finally, back in Tokyo, when he and I were alone in a hotel room, I handed him a letter saying he had been most courageous in arguing against militarism and working for reconciliation. There I assured him of my total forgiveness.

Overcome with emotion, we spent some time talking quietly, two men now united. I felt peaceful and whole again. In the months to come, my nightmares seldom returned. When we forgive others, God blesses us.

Near the end of our visit in Japan, we two couples toured a museum in Hiroshima. Our wives walked ahead as Nagase and I talked about the last days of the war. He was astonished that we prisoners had heard about the nuclear attack on Hiroshima two days before he and his unit were told.

“How could you have known?” he asked. “You had no contact with the outside world.”

“Ah,” I said. “But we had another radio.”

Together, we laughed.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Lt. Eric Lomax, "Beyond the River Kwai." from Soldier Stories (Nashville TN: W Publishing Group, 2006): 159-166.

|

|

|

|

Compiled and edited by Joe L. Wheeler. Reprinted by permission of Joe L. Wheeler. All rights reserved.

Order Soldier Stories here.

Find other Joe L. Wheeler books here.

Experienced editor and compiler Joe L. Wheeler brings a new collection of powerfully inspiring Christmas stories to the Christmas in My Heart series. These moving stories have become part of a Christmas tradition for thousands of families who have come to love their Christ-centered, love-filled message. This popular collectors series also features a collection of vintage woodcut and engraving illustrations.

Dr. Wheeler is one of the nation's leading story anthologizers. An aficionado of great stories for as long as he can remember, Wheeler is the editor/compiler of Great Stories/Classic Books collection by Focus on the Family/Tyndale House. He has also edited and compiled several other story anthologies — including Great Stories Remembered and Heart to Heart by Focus on the Family and Tyndale House; Christmas in My Heart by Review & Herald Publishing, Pacific Press, Doubleday, Tyndale House, and Focus on the Family; Forged in the Fire by Waterbrook/Random House; and Christmas in My Soul by Doubleday/Random House. Joe Wheeler's web site is here.

The Author

Lt. Eric Lomax, a British Army signals officer, was captured by the victorious Japanese during the Singapore campaign in 1942. Fascinated by railroads ever since his childhood in Edinburgh, he took what pleasure he could in the irony of his slave-labor assignment as a POW: the construction of the Burma-Siam Railroad, made famous later in the David Lean film Bridge over the River Kwai. He is the author of The Railway Man which is account of the full story which is briefly told above.

Copyright © 2006 Thomas Nelson, Inc.