Birds, Bees and Bureaucracies

- NAOMI SCHAEFER RILEY

Fascist Italy believed sex education 'sapped the virility' of the nation. Postwar Sweden encouraged it to limit the size of families.

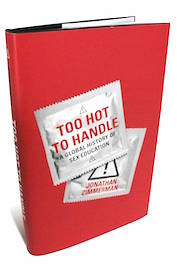

The information about sex that most parents would like their teens to know can probably be conveyed in under an hour. And yet a vast apparatus of "sex education" is now in place in American public schools — with all the laughable role-playing and modish theorizing that we are familiar with, not to mention a curriculum that can feature explicit details aimed at pre-teen children. In "Too Hot to Handle," Jonathan Zimmerman, a professor at New York University, offers welcome background to our current sex-ed regime, describing a world-wide, century-long debate over who should teach children about sex and how they should do so.

The information about sex that most parents would like their teens to know can probably be conveyed in under an hour. And yet a vast apparatus of "sex education" is now in place in American public schools — with all the laughable role-playing and modish theorizing that we are familiar with, not to mention a curriculum that can feature explicit details aimed at pre-teen children. In "Too Hot to Handle," Jonathan Zimmerman, a professor at New York University, offers welcome background to our current sex-ed regime, describing a world-wide, century-long debate over who should teach children about sex and how they should do so.

In the first half of the 20th century, Mr. Zimmerman tells us, political leaders began to think about sex education as a way of controlling the burgeoning sexual freedom of the young and also, interestingly, as a tool of social control. A British delegation presented a proposal to the League of Nations in 1928 for a "carefully devised scheme of biological training." It would help to "stimulate a sense of individual responsibility in the exercise of the racial function." Since sexual impropriety, according to certain ideas of the time, threatened to "erode the strength and dominance of white populations," eugenicists supported a sex-ed curriculum, seeing it as a way to improve mankind's genetic stock.

The Nazis, though racial supremacists par excellence, had a rather different view. German censors in 1933 barred all sex education, suggesting that it was "Marxist" as well as the work of "bourgeois individualists." In Italy, fascists regarded sex education as "Communistic" and a "practice that sapped the virility of the Italian fatherland." Critics in Western Europe had their own objections. Dutch parents used a simple slogan: "Don't Do It." They argued, in Mr. Zimmerman's summary, that "too much sexual information harmed innocent children . . . in the guise of protecting them." Sound familiar? As Mr. Zimmerman notes, Dutch opponents "captured the main arguments against sex education in the early twentieth century" and, for that matter, in the early 21st. Sex ed "exaggerated the protective value of knowledge, violated children's innocence, and trampled on the rights of parents to raise their young in the manner they saw fit."

The place where sex education seemed to gain the most ground the earliest was Scandinavia (of course). In 1956, Sweden became the first nation to require sex education in all its public schools. The idea was largely to promote birth control and, by keeping families small, "ease the burden of working mothers," according to Mr. Zimmerman. The Swedish authorities were loath to include any moral instruction with their curriculum. "We cannot acknowledge a sex education which brands all extramarital relations as sinful," wrote the Swedish Association for Sexuality Education.

Over the years, the reasons for sex education have ranged well beyond the early goals of social control or racial improvement. At one point sex ed was offered to prevent the spread of the venereal disease that soldiers had contracted during World War II. Communist nations developed their own form of sex education in the 1960s to combat the promiscuous values of the West that were, they believed, infiltrating their societies. Western leaders were particularly interested in introducing sex ed in the developing world in order to fight the coming "population bomb" in the 1970s and the famine that would supposedly follow. Though the bomb never exploded — the dire predictions of Paul Ehrlich and others were ludicrously off the mark — the fight to contain Third World population went on.

Indeed, he writes, "scholars around the world have struggled to show any significant influence of sex education upon youth sexual behavior." In which case — given how profoundly personal and culturally fraught the whole topic can be — perhaps a tie should go to the parents.

In 1994, the International Conference on Population and Development met in Cairo to push "reproductive rights" and sex education, with funding from the Ford Foundation. Leaders of countries from Guatemala to the Philippines complained that the conference's agenda was an assault on their way of life. Pakistani Premier Benazir Bhutto attempted a kind of defense: "This conference must not be viewed by the teeming masses of the world as a universal social charter seeking to impose adultery, abortion, sex education and other such matters on individuals, societies and religions which have their own social ethos."

But of course it was a kind of social charter. Traditionalists, religious and otherwise, suspect that today's schools are governed by a similar sort of agenda and strategy, aiming at sexual liberation through "education." Planned Parenthood, for instance, in its advice to people in charge of sex ed in schools, urges that their classes pursue a vast program that includes "sexual attitudes and values, sexual anatomy and physiology, sexual behavior, sexual health, sexual orientation, and sexual pleasure." The list (which goes on and on) conspicuously does not include the normative judgments by which churches and traditional families have always approached the subject.

Mr. Zimmerman's survey stops short of investigating the current world of sex ed — its ideology, curriculum and outlook — but near the end of this short volume he does pause to address a crucial empirical question. "No credible research," he writes, "has ever sustained the conservative claim that sex education makes young people more likely to engage in sex. Yet there is also scant evidence to suggest that it affects teen pregnancy or venereal disease rates." Indeed, he writes, "scholars around the world have struggled to show any significant influence of sex education upon youth sexual behavior." In which case — given how profoundly personal and culturally fraught the whole topic can be — perhaps a tie should go to the parents.

Editor's note: There is, however, a credible body of scientific research on the effectiveness of abstinence education. See "Abstinence Education in Context: The History, Evidence, Premises, and Comparison to Comprehensive Sexuality Education."

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Naomi Schaefer Riley. "Birds, Bees and Bureaucracies." The Wall Street Journal (April 30, 2015).

Naomi Schaefer Riley. "Birds, Bees and Bureaucracies." The Wall Street Journal (April 30, 2015).

Reprinted with permission of the author and The Wall Street Journal © 2015 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

The Author

Naomi Schaefer Riley is a weekly columnist for the New York Post and a former Wall Street Journal editor and writer whose work focuses on higher education, religion, philanthropy and culture. She is the author of Got Religion?: How Churches, Mosques, and Synagogues Can Bring Young People Back, Opportunity and Hope: Transforming Children's Lives through Scholarships, God on the Quad and Got Religion?. She graduated magna cum laude from Harvard University in English and Government and lives in the suburbs of New York with her husband, Jason, and their three children.

Naomi Schaefer Riley is a weekly columnist for the New York Post and a former Wall Street Journal editor and writer whose work focuses on higher education, religion, philanthropy and culture. She is the author of Got Religion?: How Churches, Mosques, and Synagogues Can Bring Young People Back, Opportunity and Hope: Transforming Children's Lives through Scholarships, God on the Quad and Got Religion?. She graduated magna cum laude from Harvard University in English and Government and lives in the suburbs of New York with her husband, Jason, and their three children.