What Schools Can Do

- WILLIAM KILPATRICK

The core problem facing our schools is a moral one.

|

All the other problems derive from it. Hence, all the various attempts at school reform are unlikely to succeed unless character education is put at the top of the agenda.

If students don't learn self-discipline and respect for others, they will continue to exploit each other sexually no matter how many health clinics and condom distribution plans are created. If they don't learn habits of courage and justice, curriculums designed to improve their self-esteem won't stop the epidemic of extortion, bullying, and violence; neither will courses designed to make them more sensitive to diversity.

Even academic reform depends on putting character first. Children need courage to tackle difficult assignments. They need self-discipline if they are going to devote their time to homework rather than television. They need the diligence and perseverance required to do this day after day. If they don't acquire intellectual virtues such as commitment to learning, objectivity, respect for the truth, and humility in the face of facts, then critical-thinking strategies will only amount to one more gimmick in the curriculum.

If, on the other hand, the schools were to make the formation of good character a primary goal, many other things would fall into place. Hitherto unsolvable problems such as violence, vandalism, drug use, teen pregnancies, unruly classrooms, and academic deterioration would prove to be less intractable than presently imagined. Moreover, the moral reform of schools is not something that has to wait until other conditions are met. It doesn't depend on the rest of society reforming itself. Schools are, or can be, one of the main engines of social change. They can set the tone of society in ways no other institution can match.

How difficult will it be to make these reforms? Very difficult. Much ground has been lost.

Some of the problems we now have are the result of stupid and naive experiments in the curriculum: the adopting of programs that let children choose their own values, and that left them morally confused. Many of these children grew up unable to make commitments, and had children of their own who, in turn, became morally confused. These programs must be discarded, and new character education and sex education curriculums must be developed in their place. But the situation has deteriorated far past the point where curriculum changes alone will reverse the slide. Courses on ethics are desirable but, at this point, hardly sufficient.

The primary way to bring ethics and character back into schools is to create a positive moral environment in schools. The ethos of a school, not its course offerings, is the decisive factor in forming character. The first thing we must change is the moral climate of the schools themselves. What we seem to have forgotten in all our concern with individual development is that schools are social institutions. Their first function is to socialize. Quite frankly, many of them have forgotten how to do that.

In the wake of the swift and decisive victory over Iraq in the Desert Storm campaign, many have asked why, if we can soundly defeat the fourth-largest army in the world in a matter of weeks, we can't turn our schools around just as decisively. The argument usually advanced is that the sort of money that went into the war could do wonders if it went into schools. I'm not so sure. Part of that victory was quite obviously due to the factor of more money and better technology. But there were other factors at work. The military had other things going for it besides money. In fact, the annual defense budget is far less than the amount of money spent annually on schools. Moreover, since the mid-fifties school budgets have, on the whole, grown every year as a proportion of total tax revenues despite the fact of a smaller school age population in recent years. Finally, even some of the wealthiest school districts have serious problems with drugs, discipline, and teen pregnancy. Money is important, if you know how to use it, but it's not the only thing.

What the military has that so many schools do not is an ethos of pride, loyalty, and discipline. It is called esprit de corps. The dictionary defines it as "a spirit of devotion and enthusiasm among members of a group for one another, their group, and its purposes." That spirit has not always been high, but after the Vietnam War, a concerted effort was made to reshape the military ethos - apparently with great success. So much so that the armed forces actually outshine the schools in doing things the schools are supposed to do best, such as teaching math, science, technological skills, history, languages, geography, and map reading. Even in the matter of racial equality - something about which educators talk incessantly - the military has shown far more success. In fact, the armed services are the most thoroughly integrated institutions in our society: promotions are on the basis of merit, black officers can dress down white soldiers, there is a spirit of camaraderie and mutual respect among the races that extends well beyond tolerance. Schools, by contrast, are rife with racial tension, hostility, and self-segregation. Not only high schools but colleges as well. According to Dinesh D'Souza's Illiberal Education and other reports, universities are far more segregated than they were twenty years ago, and the level of racial hostility is much higher.

How does the military manage to create such a strong ethos? First, by conveying a vision of high purpose: not only the defense of one's own or other nations against unjust aggression, but also the provision of humanitarian relief and reconstruction in the wake of war or natural disaster (the classic case being the role played by the American military in rebuilding war-torn Europe and Japan). Second, by creating a sense of pride and specialness (the Marines want only "a few good men") - pride reinforced by a knowledge of unit tradition, by high expectations, and by rituals, dress codes, and behavior codes. Third, by providing the kind of rigorous training - physical, mental, and technical - that results in real achievement and thus in real self-esteem. Fourth, by being a hierarchical, authoritarian, and undemocratic institution which believes in its mission and is unapologetic about its training programs.

Schools can learn a lot from the Army. That doesn't mean they need to become military schools - although, of course, there are many successful military schools. But there are enough important similarities between the two institutions to suggest that there are lessons to be learned. Both, after all, work with the same "raw material"-young men and women-and both seek to give their recruits knowledge, skills, and habits they previously lacked.

In the past, schools were run on similar lines. They had a vision of high purpose: not just preparing students for jobs and consumership, and AIDS avoidance, but preparing them for citizenship and lives of personal integrity. There was also a sense of pride in one's school - a school spirit that was reinforced at frequent assemblies, through school traditions, and by dress codes, behavior codes, and high academic standards. Schools were serious about their academic mission, and students were challenged to respond accordingly. Finally, schools were unapologetically authoritarian. They weren't interested in being democratic institutions themselves but in encouraging the virtues students would need for eventual participation in democratic institutions. Schools also had more autonomy from state and federal bureaucracies and from the courts. They could punish, suspend, and expel unruly students when and how they wished - something that is not easily accomplished these days, now that students have the right to counsel, hearings, and appeals. Some private and parochial schools still retain this climate of authority and autonomy. It may be a large part of the reason for their success. A well-known study conducted by sociologist James Coleman in the early eighties showed that parochial schools in inner cities, despite a lower level of funding, far outperformed their public counterparts. Children not only do better academically in these schools, they behave better. And they are happier. The almost absolute investment of moral authority one finds in Catholic schools creates in students not more hostility but less.

What became of the moral climate that was once so prevalent in schools? One of the most perceptive comments on its disappearance comes in a new book by Professors Edward Wynne and Kevin Ryan titled Reclaiming Our Schools: A Handbook on Teaching Character, Academics and Discipline. The authors acknowledge the destructive influence of Rousseauian philosophy in the sixties, but they also suggest that part of the explanation for the deterioration of the moral climate simply lies in the demanding nature of character education. To make rules and enforce them consistently, to give challenging assignments and correct them diligently, to keep in contact with parents and with other teachers, to police bathrooms, playgrounds, corridors, and lunchrooms, to demand respect from students and mutual respect for one another - all this requires considerable time and energy. And because it is all such hard work, there is a persistent temptation to find alternatives to it.

THE AUTHORs note that in a great many schools, a strong pattern of work avoidance prevails - avoidance by both pupils and teachers. "Students and teachers essentially carry out mutual 'pacts' to avoid creating trouble for each other. The pupils avoid conspicuous breaches of discipline . . . and the teachers do not 'hassle' pupils with demanding assignments." As time passes, though, breaches of discipline do tend to become more conspicuous. And more and more, teachers are tempted to look the other way. The upshot of this tacit agreement is that school is not taken seriously by either: both student and teacher come to look on it as a form of time serving. For the teacher teaching becomes less like a vocation and more like a job. The idea is to leave as soon as you've put in your hours, and to take home as little work as possible.

That description does not do justice, of course, to the many teachers for whom teaching is still a vocation. But the more other teachers slack off, the greater the burden placed on those who don't, and the greater the temptation for them to follow suit. Not all of these problems are created within the schools. The authors point to a number of court decisions that have helped to create an air of confusion among teachers, leaving them uncertain of their right to discipline. The result is that schools become more depersonalized, less familial. Teachers become more indifferent, retreating from the kind of engagement and concern that was possible under the older order of authority. In addition to losing the power to discipline, they lose the power to care. Their attitude becomes that of the bureaucrat toward the client he must serve.

"Much of this book," write Professors Wynne and Ryan, "is about establishing a stronger, more wholesome ethos, one which contrasts with the loose, low standards and self-oriented tone currently permeating many of our classrooms." What do they propose? The key phrase is "profound learning"-learning that is absorbed by participation in the activities and pursuits of a serious community. This "serious, non-sentimental conception of education" is opposed to the doctrines of "learning is fun" and "happy think" which have reduced education to a game of trivial pursuits. "It is impossible," they contend, "to form 'strong personalities' without a profound molding system." Although such a system is subject to abuse, there is really no substitute for it. Why pretend that schools can be democracies when they so clearly cannot?

Wynne and Ryan agree with Aristotle that learning character is largely a matter of habituation. Consequently, one of the main ways to develop character is to provide planned activities which invite students to practice good habits. The authors suggest a number of such activities, among them tutoring younger pupils and school service projects to the community. Equally important are behavior and discipline codes which serve as guides to behavior, and which need to be clearly identified and enforced. School-wide policies need to be specified about such matters as cheating, overt acts of affection, fighting, dress codes, disobedience and disrespect, vulgar language, and so on. The list would depend upon the particular school and upon past experience.

The same holds true for individual classrooms. The authors point to research showing that "effective teachers spend a significant amount of time during the first two weeks of school establishing rules and procedures . . . such veterans seemingly sacrifice a great deal of time on drilling or 'grooving' students on classroom procedures in the early weeks." It's hard work but it pays off, say the authors:

We know a first year teacher who patiently explained to his fifth grade students that they were not to talk in the hall on their way to gym. He soon discovered that the message did not get through. Instead of letting it go on or displaying aimless anger, he had them come back. He explained again and gave them another chance. They talked. He called them back again. Having missed twenty minutes of precious gym time, his fifth graders made it on the fifth try. There was no more talking in the halls and many other messages got through with greater speed and accuracy.

Naturally, rules need punishments to back them up. Strangely, when one considers how much of a teacher's time is taken up with unruly student behaviors, textbooks for teachers devote very little space to the subject - and much of that "surrounded with warnings about the dangers of punishment." Professors Wynne and Ryan are less reticent. They have a lot to say about punishment, about how and when to apply it, and what it should consist of.

Isn't it better that people behave themselves without compulsion? Yes, eventually, but sometimes compulsion is what is needed to get a good habit started. We don't wait for a child to decide for himself that tooth brushing is a good habit. The same applies to weightier moral matters. "You can't legislate morality" is a terribly simplistic formula. In fact, many laws are aimed at legislating morality, and - if morality is understood as proper conduct - many of them are quite effective at doing so. Rules and laws can even work to change habits of the heart. I think there can be little doubt that the civil rights legislation of the sixties had that effect. Laws granting equality of access to blacks in the South may have been hated and obeyed grudgingly at first. Nevertheless, obeying the law over a long period of time induces certain habits which alter attitudes. Many southerners have had a change of heart about issues of basic fairness.

Schools, like society at large, need to insist on proper habits of conduct. "At this moment in our history," observe Wynne and Ryan, "too many public schools are overly permissive. Thus, they fail to instill in our young the self-discipline needed for citizenship and full adult development. We believe strict schools (certainly by today's standards) are happy schools and, more important, schools that serve children and society well."

The ethos that the authors suggest, however, could hardly be called a legalistic one. Their concern is to show how educators can create a sense of pride and specialness - of classroom spirit and school spirit. In the best schools, they suggest, there is a strong sense of family and community. The attitude teachers communicate is one of "You belong to me" and "I belong to you." This sense of spirit and specialness can be reinforced by mottoes, posters, pictures, pledges, symbols, and song. For example, they recommend that schools might consider developing a list of songs "of relatively persisting value which all students . . . and faculty should learn and sing together." For emphasis, they quote a nineteenth-century description of students at Harrow singing at mealtime: "When you hear the great volume of fresh voices leap up as larks from the ground, and swell and rise, till the rafters seem to crack and shiver, then you seem to have discovered all the sources of emotion." (It's worth noting, by the way, that some of our most successful drug rehabilitation programs use group singing - sometimes involving more than a hundred youngsters and staff - as a method of creating a new sense of identity and purpose.)

The final chapters of Reclaiming Our Schools are devoted to the importance of ceremonies in transmitting moral values. This is another area that is almost entirely neglected in educational research. Although they are often considered extraneous to the real business of school, rituals and ceremonies are among the most effective ways of impressing students with the significance of values held in common. As Wynne and Ryan put it, "Public, collective activities have teaching power because we are properly impressed with values to which large numbers of persons display dramatic, conspicuous allegiance or respect." Graduation ceremonies are a prime example. Among other things, they signify the importance of learning, and the value placed on it by the community. The authors suggest that educators need to deliberately design more such school ceremonies as a means of transmitting vital messages.

It should be apparent at this point that what is being suggested here is radical in the context of today's schools. It is quite different from the two current models of schooling - the laissez-faire model, on the one hand, and the rationally based managerial model, on the other. It is a much more comprehensive view because it takes account of all the elements that go into good schooling: not just academics but character, pride, symbol, and ritual. As opposed to the superficial fun culture children encounter outside of school, it is a counterculture in the true sense.

To some ears, the measures proposed in Reclaiming Our Schools will sound excessive. However, in some cases, even stronger measures are needed. In the last few years, for example, a number of black educators have been calling for all-male, allblack schools run by black, male teachers. The argument is that boys need appropriate discipline as well as role models. But male role models are in short supply. Schools are staffed mainly by women, not men. (Last year, for example, Boston College's School of Education graduated over 200 students; only five of them were males.) The situation is intensified in the inner city. Not only are there few male role models in the school, there are few at home. Because of many factors, homes are dominated by females. The main source of male models, then, is to be found in the streets. And, as has always been the case with boys, the tendency is to identify with those who have power. Sometimes, fortunately, this means following in the steps of an older athlete, youth worker, or policeman. But often it means that drug dealers and gang members set the tone and temper of youthful aspirations.

I'm not convinced that such schools should be for blacks only or that they need Afrocentric curriculums, as is sometimes proposed. Both ideas are ill advised. But the idea of all-male schools makes sense. The lives of inner-city youth are so much at risk (the leading cause of death for black males up to age forty-four is homicide) that radical measures are in order. And the principle behind this particular measure is a sound one. In fact, it is not especially radical. The idea that boys should be taught by men is an ancient and honorable one, practiced for centuries across a wide variety of cultures and settings, ranging from primitive tribes to English boarding schools. This idea also has a substantial basis in psychology, sociology, cultural anthropology, and criminology. It has long been known in these fields that boys have a more difficult time than girls in the formation of sex identity. The fewer strong male models in a boy's life, the more trouble he has. In the absence of an involved and committed male, boys tend to form simplified and stereotyped notions of maleness. Surrounded by women, desperately anxious to establish their maleness, they often compensate for their insecure sense of identity by adopting a hypermasculine aggressive pose. As is now well known, boys without fathers are substantially more involved in delinquency and violence than boys with fathers at home. When they go to school, they bring this aggressiveness with them.

The answer to masculine overcompensation is not to surround boys with more women at school and expect them to adopt a "let's-be-nice-to-each-other" attitude. As even the most ardent of feminist psychologists now admit, boys are inherently-biologically-more aggressive than girls. They need to do something with that aggressiveness. Either it has to be channeled by adults who are strong enough to channel it, or it erupts in ways that are destructive both to the individual and to society.

Other societies have found ways to do this. Initiation rites, for example, are elaborately constructed educational devices for teaching both boys and girls how to grow up. In most societies, the preparation period for these rituals (many months, in some cases) involves the segregation of boys and girls. Boys are prepared by the men, and girls are prepared by the women. Although some of the final rituals may involve boys and girls together, certain parts of the initiation process are distinct-the rituals for boys involving more active displays of initiative and physical courage. The upshot is that young males are provided an opportunity to affirm their manhood under the tutelage of adult males. They prove themselves within a social framework, rather than at the expense of society.

The same system holds in the Army, which for very good reasons was until recently a sex-segregated institution. In boot camp, the drill instructor functions in a way similar to the male supervisors of initiation rites. He expects the recruits to act like men, he offers himself as a model, he puts them through arduous initiation exercises. As a result, he is simultaneously hated and admired. The recruits resent his demands, yet they respect his abilities. Secretly they want to be like him - at least in some crucial respects. Secretly, also, they know he has their best interests at heart. It is a process of maturation through identification and through ritual challenge. The film An Officer and a Gentleman is a good - if somewhat overdramatized - depiction of the process.

All of this is sometimes difficult for women to comprehend. Indeed, it must seem slightly absurd. Because women possess a stronger sense of sexual identity, they don't as a rule feel a corresponding compulsion to prove their womanhood. This difference between men and women is reflected in the practices of primitive societies. Initiation rites for women are usually in the nature of an acknowledgment of what is already present rather than - as in the case of male rituals - an attempt to create something that does not yet exist. As Margaret Mead observed of the societies she studied: "The worry that boys will not grow up to be men is much more widespread than the worry that the girls will not grow up to be women. . ." The latter fear, she noted, is almost nonexistent.

"Why can't a woman be more like a man?" asks Professor Henry Higgins in My Fair Lady. But for many women the question is just the reverse. The answer seems to be as follows: Growing up into the socialized world of adults is a more natural process for a woman. For a man it requires more of a transformation. His natural inclinations are short-term, aggressive, irresponsible. Boys have little natural interest in babies, or in eventually growing up to raise their own. For the average boy masculinity does not mean the steady, responsible life of a husband and father but rather masculine exploits centered around strength and bravery. Attempts to teach the right type of masculinity directly - for example, classes in homemaking or child care - are like attempts to teach self-esteem directly: they don't have much impact unless other things are in place. A young man needs to develop some assurance about his basic masculinity before he can learn the more responsible kind of masculinity. Thus the importance of transformative institutions for boys: rites of passage, boarding schools, military service. These are the kinds of institutions that can provide a "profound molding" experience. Those who have seen a male friend or relative go off to the Army or to military school or merely to Boy Scout camp can attest to these transformative powers. I recall a classmate in high school, a gawky, aimless, passive boy, the butt of countless jokes, who nevertheless somehow managed to enlist in the Marine Corps. When I met him again five years later, he had become a thoroughly adult, thoroughly calm and confident man. He told me that he was about to open his own construction business. After talking with him, I had no doubt he would succeed - and he did.

There is a risk to such all-male groups: If not handled properly, the training process can result in misogyny, insensitivity, and a collectivist mind set. Instead of moving on to a greater maturity, young men can get fixated on the initiation process itself - forever in the process of proving themselves. But these dangers could be easily avoided at the grade school and high school level, especially since the institutional aim would not be preparation for war but education in character and academics.

In communities with strong fathers at home and positive male role models in the neighborhood, coed schools staffed mostly by females can do a decent job in educating and socializing boys. But where those other conditions have broken down, the idea of all-male schools run by men makes sense. These might or might not be boarding schools. That would depend on the local situation. They don't have to be military schools, but-in this age of commitment to diversity - that option ought certainly to be entertained. As writer Leon Podles puts it:

Why can't some schools be run for boys by men? A dozen military schools in each inner city, complete with uniforms, drill, and supervised study, staffed by retired black and white officers (without education degrees) would go far to making our cities livable, and giving black boys a shot at a decent life.

Such schools, as I have indicated, would serve as a counterculture. They would provide a code and aesthetic counter to, and more attractive than, gang life. They could establish an ethos of pride and purposefulness, and in doing so, they could transform the lives of a generation that might otherwise become yet another lost generation.

Is this draconian? Let me suggest that the status quo is far more draconian. As it is, more young black males in our society go on to prison than go on to college. Meanwhile inner-city dwellers live in constant fear of crime and random violence. And if we are worried about public schools that might resemble military schools, we should keep in mind that many inner-city schools have already begun to resemble prisons in their attempts to seal themselves off from outside dangers.

Unfortunately, the few attempts to institute all-male public schools have run afoul of feminist ideology and sex discrimination statutes. For example, last year in Detroit, a federal judge ruled that an all-male inner-city school could not open unless it admitted girls. Thus the chances of both boys and girls were sacrificed for an abstract notion about gender equality. Although the ruling reflects current sensibilities among upper-class whites, it is at variance with the real psychological and social needs of inner-city children. It tends to confirm the judgment of one of Dickens's characters, who declares, "The law is a ass." (In the same vein, the civil rights division of the justice Department has tried to force the Virginia Military Institute to admit women. In this case, however, the law was not an "ass." Judge Jackson Kiser, following the advice of scholars like Harvard's David Riesman, ruled that-in the name of diversity-VMI ought to be allowed to march "to the beat of a different drummer.")

One could, of course, argue that though forceful measures may be necessary in inner-city schools, this is not the case in suburbs. Does Elmwood High really need the steps outlined earlier - increased attention to rules and conduct, stronger discipline and punishment? Does it need increased attention to ritual, symbol, and ceremony? And aren't these forms of mind manipulation? My answer is essentially the same. Would you rather a youngster learn discipline in school, or later on from a probation officer, a drug rehabilitation center, a divorce court judge, or the boss who fires him? Should males learn habits of the heart when they are young, or should they learn them belatedly from a harassment officer on the job or at college? When a society fails to develop character in its young people, it is forced to adopt all sorts of poor substitutes for it when they grow up. In colleges and workplaces across the country, we are now seeing the creation of draconian harassment codes which spell out in minute detail exactly how men and women are to behave toward one another (codes that in many cases are unconstitutional) - all because they failed to learn certain codes and habits by heart at an earlier age. Thomas Jefferson said, "That government is best which governs least," but the rest of the quote - the part that is usually left out - continues, "because its people discipline themselves." Without such self-discipline, learned at an early age, we are only inviting more control of our adult lives by governments, courts, and bureaucracies.

But besides these indirect methods, which work at changing the school environment, there are more direct methods of teaching character. Over the course of the last six or seven years, a small but growing number of schools have been devising explicit ways to teach the virtues. One such system is the North Clackamas School District in Oregon. Teachers there have developed a four-year cycle designed to emphasize a particular set of character traits each year. Year one concentrates on patriotism, integrity and honesty, and courtesy; year two focuses on respect for authority, respect for others, for property, and for environment, and selfesteem; year three, on compassion, self-discipline and responsibility, work ethic, and appreciation for education; year four, on patience, courage, and cooperation. After the first four years of school, the cycle begins again with the difference that students are now expected to understand these traits on a deeper level. The curriculum includes definitions, the study of people from the past and present who have demonstrated a particular virtue, concrete ways of putting the virtue into practice, and activities such as poster, essay, or photo contests. Here are examples of definitions:

Patience is a calm endurance of a trying or difficult situation.

Patience reflects a proper appreciation and understanding of other people's beliefs, perceptions or conditions. Patience helps one to wait for certain responsibilities, privileges or events until a future maturity level or scheduled time.

Patience is: ·

- waiting one's turn.

- appreciatingpeople's differences.

- enduring the skill levels of younger children when playing a game.

Courage is upholding convictions and what is right or just.

Courage is being assertive, tenacious, steadfast and resolute in facing challenges and social pressures.

Courage is: ·

- resisting negative peer pressure and providing positive peer pressure.

- being loyal to someone even though social popularity may dictate otherwise.

- defending the rights of self and others.

After learning these definitions, students are encouraged to discuss the concepts. Although the character trait itself is never called into question, there is room for exploring its proper application. For instance, the unit on respect for authority asks students to research examples of legitimate resistance to authority - examples such as Thomas Jefferson, Rosa Parks, and Martin Luther King, Jr.

One problem with such lists is that it's difficult to agree on what should be put in and what left out. For example, I'm not convinced that self-esteem is a virtue. Nevertheless, these are character traits that most parents in most communities would endorse. In the last analysis, each school district would have to make its own determination. However, there is at least one important reference point. Most scholars who advocate a character education approach are agreed that, as a bare minimum, every list ought to contain the four cardinal virtues that have come down to us from the Greeks: prudence, justice, courage, and temperance. They are called cardinal because they are the axis (cardo) on which the moral life turns. They are, of course, sometimes known by other names. Prudence is "wisdom" or "practical wisdom," courage is "fortitude," temperance is "self-discipline" or "self-control."

It is difficult to improve on what the classical writers said on the subject of the virtues, and a teacher who takes the time to read up on the subject will find that, presented in the right way, the classic conception of the virtues is capable of generating many rewarding discussions. Among other things, such discussions could examine the notion that the virtues form a unity: that in order to be a person of character, you must have all four working together. What good is it, for example, to believe in justice if you lack the courage to stand up for someone unjustly accused? And what good is courage if you lack justice and wisdom? (The Vikings were courageous in battle, but exceedingly cruel to their victims. It is brave to administer first aid to a wounded man on a battlefield, but not very helpful unless you know what you're doing.) Aristotle's notion that each virtue is a mean between two extremes should also come in for discussion. Courage, for example, is opposed not only to cowardice but also to foolhardiness. A man who lacks sufficient respect for the dangers involved is not a courageous man but a foolish man. In fact, Aristotle said that only the man who feels fear yet overcomes it for the sake of a good deed should be called courageous.

A number of other things could be said on the virtue of courage. Students ought to learn the difference between physical courage, moral courage, and intellectual courage, and that people who have physical courage do not necessarily possess the other two. And they need to know that courage is not confined to spectacular acts of bravery. In a letter to his children, Edwin Delattre talks about another kind of heroism:

Still heroism is more than this. It doesn't mean just doing particular actions that are brave. It means being the kind of person who does not run away when physical, moral, or intellectual bravery is called for. So, for example, you might have a woman whose husband dies and leaves her to raise several young children by herself. The person who does not run away, who does her best to be a good parent in these difficult circumstances exhibits deep and continuing bravery and so is especially heroic, even though there may be no single events like rescuing a drowning person to catch our attention. It is a quiet, durable heroism that consists of facing up to whatever the world puts before us and refusing to give up. This is the heroism that deserves respect above all, and the place to look for it is in the people you know and love.

Before teachers can teach about the virtues, however, they may need to brush up on the classical sources. One school that has provided such preparation for its teachers is the Thomas Jefferson High School of Science and Technology in Alexandria, Virginia. During the summer of 1990, thirty-five members of the school's faculty attended a three-week institute to study the foundations of ethics in Western society. The program centered on Plato's Republic and five of his other dialogues, Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics, and selections from four books of the Bible: Genesis, Exodus, Samuel, and Matthew. These texts, according to the institute's descriptive summary, raise fundamental questions: "What is a good life? What constitutes good character? What is virtue? What is a good society? . . . In essence, what kind of human beings should we be?" During the summer institute and in seven follow-up sessions during the school year, teachers also discussed concrete ways these ideas could be incorporated into the social studies and English curriculums. By the middle of the school year teachers reported a changed atmosphere: students had become excited about virtue, and many of them had taken to wearing the institute's special T-shirts, which depict Plato and Aristotle walking together, engrossed in conversation.

Professor Christina Hoff Sommers describes a similar response on the part of college students. Sommers originally employed a dilemma format in her ethics course at Clark University, but she became disturbed by student comments on the course evaluation forms, such as one student's remark "I learned there was no such thing as right or wrong, just good or bad arguments." As a result, Sommers decided to teach a course on the philosophy of virtue, with an emphasis on Aristotle:

Students find a great deal of plausibility in Aristotle's theory of moral education, as well as personal relevance in what he says about courage, generosity, temperance and other virtues. I have found that an exposure to Aristotle makes an immediate inroad on dogmatic relativism; indeed the tendency to dismiss morality as relative to taste or social fashion rapidly diminishes and may vanish altogether. Most students find the idea of developing virtuous character traits naturally appealing.

Sommers continues:

Once the student becomes engaged with the problem of what kind of person to be, and how to become that kind of person, the problems of ethics become concrete and practical and, for many a student, morality itself is thereafter looked on as a natural and even inescapable personal undertaking.

One of the best ways to teach the virtues is in conjunction with history and literature. In that way, students can see that they are more than abstract concepts. In Robert Bolt's play A Man for All Seasons, we see a remarkable combination of all four virtues in one man, Sir Thomas More. The plot of High Noon revolves around a tension among justice, courage, and prudence. To Kill a Mockingbird shows one kind of courage, The Old Man and the Sea another. Measure for Measure and The Merchant of Venice teach us about justice. Moby-Dick depicts a man who has lost all sense of prudence and proportion. In the character of Falstaff, we are treated to a comic depiction of intemperance; in the story of David and Bathsheba, we are shown a much harsher view of a man who yields to his desires.

History and biography offer innumerable examples of virtue in action. A very short list for this century would include Jane Addams, Marie Curie, Winston Churchill, Douglas MacArthur, Anne Frank, Raoul Wallenberg, Rosa Parks, Ruby Bridges, Lech Walesa, and Benigno Aquino. It is true that great persons sometimes also have great faults. But for a student who has learned something of the virtues, and of the difficulty of possessing them, such revelations, when they come, are less likely to be occasions of cynicism. He can understand that people are not measured by occasional failings but by their whole lives.

A study of the cardinal virtues in conjunction with history and literature can lead to worthwhile classroom discussions. Notice, however, that such discussions are a far cry from Values Clarification exercises based on nothing but a student's feelings or uninformed opinions. In one case, students carry out their discussions within a framework of moral wisdom. In the other, there is no framework, and morality becomes a matter of "what I say" versus "what you say." A knowledge of the virtues provides a standard by which opinions and feelings can be measured. A student who has begun to understand them can more accurately weigh moral arguments. He can begin to discriminate between values that change and values that don't. He can learn the difference between values that are subjective (a preference for frozen yogurt over ice cream) and values that are objective (the obligation under justice to share food with someone who is hungry, the obligation under temperance not to gorge yourself to the point of throwing up).

Knowledge of the virtues also gives students a gauge for choosing their models. Many young people confuse fame with heroism. They can begin to ask not only what the difference is between a hero and a celebrity but also what the difference is between someone who has physical courage (a sports hero) and someone who has both physical and moral courage (an Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, a Martin Luther King, Jr.). They will then be in a better position to decide which qualities of famous people are worth emulating, and which are not. I am not suggesting that discussion be aimed at picking apart a student's favorite hero. Such a discussion of qualities doesn't require a naming of names. However, in the case of some famous people whose personal lives and indiscretions have become a matter of public record, that may be unavoidable. Students will bring them up anyway. For example, since the case of Earvin "Magic" Johnson has been thrust onto the public scene, it provides an opportunity for making some distinctions. Johnson is certainly courageous in both the physical and moral sense. It takes physical courage to play professional basketball; it takes physical courage to face the pain of disease. It took moral courage to make his announcement when he did instead of waiting. Johnson does not, however, seem to have made much effort to practice the virtue of temperance. A Los Angeles Times reporter who knows Johnson well was quoted in Newsweek as suggesting that Johnson slept with more than a thousand women. How about prudence? Certainly his sexual activities were not prudent. But beyond that lies the question of the wisdom of his anti-AIDS campaign tactics. Johnson originally took a stand in favor of safe sex, not abstinence. Is that prudent advice, or does it, by legitimizing teen sex, simply increase sexual activity and lead to more, not fewer, cases of AIDS? A similar question could be asked about Johnson's more recent advocacy of both safe sex and abstinence. Is that a clear message or merely a confusing one? (A further question, of course, is why we should look to basketball players for wisdom. Does the fact that we do so suggest that something is out of order in our priorities?) The virtue of justice? Johnson seems to be a just man in many respects. He has not been stingy with either his time or his money in helping the less fortunate. On the other hand, the women he put at risk might question whether Johnson acted justly in relation to them.

The purpose of such a discussion would not be to make classroom capital out of a tragic situation, or to either condemn or exonerate Magic Johnson. The virtues are not clubs to hit other people over the head with but strengths that we should try to acquire in our own lives. But just as Magic Johnson's sickness has been made an opportunity for AIDS awareness, it could also serve as an opportunity for increased virtue awareness-in the final analysis, a much better weapon against AIDS.

The United States has an AIDS problem and a drug problem and a violence problem. None of this will go away until schools once again make it their job to teach character both directly, through the curriculum, and indirectly, by creating a moral environment in the school. Schools courageous enough to reinstate and reinforce the concept and practice of the virtues will accomplish more toward building a healthy society than an army of doctors, counselors, and social workers.

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

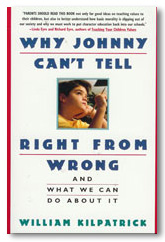

Kilpatrick, William. "What Schools Can Do." Chapter 13 in Why Johnny Can't Tell Right from Wrong and What We Can Do About It. edited by J.H. Clarke, (New York: A Touchstone Book, 1992), 225 - 244.

Reprinted by permission of William Kilpatrick.

The Author

William Kilpatrick is the author of several books on religion and culture including Christianity, Islam, and Atheism: The Struggle for the Soul of the West and Why Johnny Can't Tell Right from Wrong. For more on his work and writings, visit his Turning Point Project website.

Copyright © 1993 Touchstone books