The Holy See's Teaching On Catholic Schools

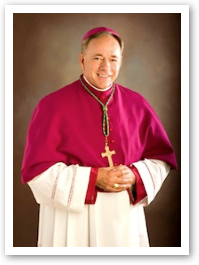

- ARCHBISHOP J. MICHAEL MILLER, C.S.B

The Holy See, through its documents and interventions, whether of the Pope or of other Vatican offices, sees in Catholic schools an enormous heritage and an indispensable instrument in carrying out the Church's mission in the third Christian millennium. Ensuring their genuinely Catholic identity is the Church's greatest challenge.

|

Thank you very much for your kind invitation, extended through Frank Hanna and Alejandro Bermudez, to address you this afternoon on a subject of such vital importance to the future of the Church and the nation. It is a pleasure to be with a group so dedicated to the cause of Catholic education, and, especially in making Catholic schools available to those whose economic means might otherwise deprive them of one of the Church's most valuable resources for building up the Body of Christ.

Right from the days of their first appearance in Europe, Catholic schools have generously served the needs of the "socially and economically disadvantaged" and have given "special attention to those who are weakest." The vision set out by the Second Vatican Council confirmed this age-old commitment: the Church offers her educational service in the first place, the Fathers affirmed, to "those who are poor in the goods of this world or who are deprived of the assistance and affection of a family or who are strangers to the gift of faith." The Solidarity Association, with its providential name which embodies the heritage of our beloved Pope John Paul II, is inserted in the long tradition of St. Angela Merici, St. Joseph of Calasanz, St. Jean Baptiste de la Salle, St. John Bosco and so many other Religious and lay people who generously dedicated themselves to Christ's love for the poor, the humble and the marginalized in their educational apostolate.

My intervention's theme, "the Holy See's teaching on Catholic education," is vast, far too vast to be summarized in one brief lecture. Even so, I will try to introduce into the conversation the major concerns that can be found in the Vatican documents published since Vatican II's landmark Decree on Christian education Gravissimum Educationis. In this talk I shall draw on the conciliar document, the 1983 Code of Canon Law in its section on schools, and the five major documents published by the Congregation for Catholic Education: The Catholic School (1977); Lay Catholics in Schools: Witnesses to Faith (1982); The Religious Dimension of Education in a Catholic School (1988); The Catholic School on the Threshold of the Third Millennium (1997); and Consecrated Persons and their Mission in Schools: Reflections and Guidelines (2002). Among these documents, in particular I would like to recommend for your study The Catholic School and The Religious Dimension of Education in a Catholic School. First I will say something about parental and government rights, followed by some remarks on the school as an instrument of evangelization, and then describe the five components which must be present if a school is to have a genuinely Catholic identity.

I. Parental and State Responsibilities

It is the clear teaching of the Church, constantly reiterated by the Holy See, that parents are the first educators of their children. Parents have the original, primary and inalienable right to educate them in conformity with the family's moral and religious convictions. They are educators precisely because they are parents. At the same time, the vast majority of parents share their educational responsibilities with other individuals and/or institutions, primarily the school.

Elementary education is, then, "an extension of parental education; it is extended and cooperative home schooling." In a real sense schools are extensions of the home. Parents, not schools, not the State, and not the Church, have the primary moral responsibility of educating children to adulthood. The principle of subsidiarity must always govern relations between families and the Church and State in this regard. As Pope John Paul II wrote in his 1994 Letter to Families:

Subsidiarity thus complements paternal and maternal love and confirms its fundamental nature, inasmuch as all other participants in the process of education are only able to carry out their responsibilities in the name of the parents, with their consent and, to a certain degree, with their authorization.

For subsidiarity to be effective families and those to whom they entrust a share in their educational responsibilities must enjoy true liberty about how their children are to be educated. This means that "in principle, a State monopoly of education is not permissible, and that only a pluralism of school systems will respect the fundamental right and the freedom of individuals – although the exercise of this right may be conditioned by a multiplicity of factors, according to the social realities of each country."

Thus, the Catholic Church upholds "the principle of a plurality of school systems in order to safeguard her objectives." Moreover, "the public power, which has the obligation to protect and defend the rights of citizens, must see to it, in its concern for distributive justice, that public subsidies are paid out in such a way that parents are truly free to choose according to their conscience the schools they want for their children." This obligation of the State to provide public subsidies also arises because of the contribution which Catholic schools make to society.

Indeed, most countries with substantial Christian majorities provide such assistance: Australia, Canada, England, Belgium, the Netherlands, France, Germany, Spain, Scotland, Ireland, just to name a few. The United States, Mexico, and Italy are exceptions in not providing any assistance. In summary fashion the recently published Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church (2005) states laconically that "the refusal to provide public economic support to non-public schools that need assistance and that render a service to civil society is to be considered an injustice."

II. The Church, Evangelization and Education

What role does the Church play in assisting Catholic families in education? By her very nature the Church has the right and the obligation to proclaim the Gospel to all nations (cf. Mt 28:20). In the words of Gravissimum Educationis:

To fulfill the mandate she has received from her divine founder of proclaiming the mystery of salvation to all men and of restoring all things in Christ, Holy Mother the Church must be concerned with the whole of man's life, even the secular part of it insofar as it has a bearing on his heavenly calling. Therefore, she has a role in the progress and development of education.

In a special way, the duty of educating is an ecclesial responsibility: "The Church is bound as a mother to give to these children of hers an education by which their whole life can be imbued with the spirit of Christ." Note, however, that parents do not surrender their children to the Church but share a common undertaking.

Certainly the Church was involved in education before she established schools. Nonetheless, today the principal, but not only, help which the Church offers families is by establishing Catholic schools which ensure the integral formation of children.

Catholic schools participate in the Church's evangelizing mission, of bringing the Gospel to the ends of the earth. More particularly, they are places of evangelization for the young. As truly ecclesial institutions, they are "the privileged environment in which Christian education is carried out." Catholic schools also have a missionary thrust, by means of which they make a significant contribution "to the evangelizing mission of the Church throughout the world, including those areas in which no other form of pastoral work is possible."

Precisely because of this evangelizing mission, our schools, if they are to be genuinely ecclesial – and they must be that if they are to be authentically Catholic – must be integrated within the organic pastoral activity of the parish, diocesan and universal Church. "Unfortunately, there are instances in which the Catholic school is not perceived as an integral part of organic pastoral work, at times it is considered alien, or very nearly so, to the community. It is urgent, therefore, to sensitize parochial and diocesan communities to the necessity of their devoting special care to education and schools."

The Catholic school, therefore, should play a vital role in the pastoral activity of the diocese. It is a pastoral instrument of the Church for her mission of evangelization. The bishop's leadership is pivotal in lending support and guidance to Catholic schools: "only the bishop can set the tone, ensure the priority and effectively present the importance of the cause to the Catholic people."

![]() III. Five Essential "Marks" of Catholic Schools

III. Five Essential "Marks" of Catholic Schools

Now let's turn to a discussion of the question to which the Holy See addresses its most serious attention. Its documents repeatedly emphasize that certain characteristics must be present if a school is to be considered Catholic. Like the "marks" of the Church proclaimed in the Creed, so, too, does it identity the principal features of a school qua Catholic. For the purpose of this talk I will expand the four ecclesial marks to five scholastic ones!

As the Holy Father reminded a group of American bishops on their most recent ad limina visit: "It is of utmost importance, therefore, that the Church's institutions be genuinely Catholic: Catholic in their self-understanding and Catholic in their identity. All those who share in the apostolates of such institutions, including those who are not of the faith, should show a sincere and respectful appreciation of that mission which is their inspiration and ultimate raison d'être." It is precisely because of its Catholic identity, which is anything but sectarian, that a school derives the originality enabling it to be a genuine instrument of the Church's apostolic mission. Let's, then, look at these five non-negotiables of Catholic identity, the lofty ideals proposed by the Holy See which inspire the Church's enormous investment in schooling.

1. Inspired by a Supernatural Vision

The enduring foundation on which the Church builds her educational philosophy is the conviction that it is a process which forms the whole child, especially with his or her eyes fixed on the vision of God. The specific purpose of a Catholic education is the formation of boys and girls who will be good citizens of this world, enriching society with the leaven of the Gospel, but who will also be citizens of the world to come. Catholic schools have a straightforward goal: to foster the growth of good Catholic human beings who love God and neighbor and thus fulfill their destiny of becoming saints.

If we fail to keep in mind this high supernatural vision, all our talk about Catholic schools will be no more than "a gong booming or a cymbal clashing" (I Cor 13:1).

2. Founded on a Christian Anthropology

Emphasis on the supernatural destiny of students, on their holiness, brings with it a profound appreciation of the need to perfect children in all their dimensions as images of God (cf. Gen 1:26-27). As we know, grace builds on nature. Because of this complementarity of the natural and supernatural, it is especially important that all those involved in Catholic education have a sound understanding of the human person. Especially those who establish, teach in and direct a Catholic school must draw on a sound anthropology that addresses the requirements of both natural and supernatural perfection.

For Catholic schools to achieve their goal of forming children, all those involved – parents, teachers, staff, administrators and trustees – must clearly understand who the human person is. Again and again the Holy See's documents repeat the need for an educational philosophy built on the solid foundation of sound Christian anthropology. How do they describe such an anthropological vision? In Lay Catholics in Schools: Witnesses to Faith the Vatican proposes a response:

In today's pluralistic world, the Catholic educator must consciously inspire his or her activity with the Christian concept of the person, in communion with the Magisterium of the Church. It is a concept which includes a defense of human rights, but also attributes to the human person the dignity of a child of God; it attributes the fullest liberty, freed from sin itself by Christ, the most exalted destiny, which is the definitive and total possession of God himself, through love. It establishes the strictest possible relationship of solidarity among all persons; through mutual love and an ecclesial community. It calls for the fullest development of all that is human, because we have been made masters of the world by its Creator. Finally, it proposes Christ, Incarnate Son of God and perfect Man, as both model and means; to imitate him, is, for all men and women, the inexhaustible source of personal and communal perfection.

All this says nothing more than the words from Gaudium et Spes so often quoted by Pope John Paul II: "it is only in the mystery of the Word made flesh that the mystery of man truly becomes clear."

The Holy See's documents insist that, to be worthy of its name, a Catholic school must be founded on Jesus Christ the Redeemer who, through his Incarnation, is united with each student. Christ is not an after-thought or an add-on to Catholic educational philosophy but the center and fulcrum of the entire enterprise, the light enlightening every pupil who comes into our schools (cf. Jn 1:9). In its document The Catholic School, the Congregation stated:

The Catholic school is committed thus to the development of the whole man, since in Christ, the perfect man, all human values find their fulfilment and unity. Herein lies the specifically Catholic character of the school. Its duty to cultivate human values in their own legitimate right in accordance with its particular mission to serve all men has its origin in the figure of Christ. He is the one who ennobles man, gives meaning to human life, and is the model which the Catholic school offers to its pupils.

The Gospel of Christ and his very person are, therefore, to inspire and guide the Catholic school in its every dimension: its philosophy of education, its curriculum, community life, its selection of teachers, and even its physical environment. As John Paul II wrote in his 1979 Message to the National Catholic Educational Association of the United States: "Catholic education is above all a question of communicating Christ, of helping to form Christ in the lives of others."

That Christ is the "one foundation" of Catholic schools is surely not news to anyone here. Nevertheless, this conviction, in its very simplicity, can sometimes be overlooked. Having a sound, anthropology enables Catholic educators to recognize Christ as the standard and measure of a school's catholicity, "the foundation of the whole educational enterprise in a Catholic school," and the principles of the Gospel as guiding educational norms.

3. Animated by Communion and Community

A third important teaching on Catholic schools that has emerged in the Holy See's documents in recent years is its emphasis on the community aspect of the Catholic school, a dimension rooted both in the social nature of the human person and the reality the Church as a "the home and the school of communion." That the Catholic school is an educational community "is one of the most enriching developments for the contemporary school." The Congregation's Religious Dimension of Education in a Catholic School sums up this new emphasis:

The declaration Gravissimum Educationis notes an important advance in the way a Catholic school is thought of: the transition from the school as an institution to the school as a community. This community dimension is, perhaps, one result of the new awareness of the Church's nature as developed by the Council. In the Council texts, the community dimension is primarily a theological concept rather than a sociological category.

Ever more Vatican statements emphasize that the school is a community of persons and, even more to the point, "a genuine community of faith."

I would like to mention three particular ways in which the Holy See would like to see the development of the school as a community: the teamwork or collaboration among all those involved; the interaction of students with teachers and the school's physical environment.

Elementary schools "should try to create a community school climate that reproduces, as far as possible, the warm and intimate atmosphere of family life. Those responsible for these schools will, therefore, do everything they can to promote a common spirit of trust and spontaneity." This means that all involved should develop a real willingness to collaborate among themselves. Teachers, Religious and lay, together with parents and trustees, should work together as a team for the school's common good and their right to be involved in its responsibilities. The Holy See is ever careful to foster the appropriate involvement of parents in Catholic schools. Indeed, more than in the past, teachers and administrators must often encourage parental participation. Theirs is a partnership directed not just to dealing with academic problems but to planning and evaluating the effectiveness of the school's mission.

A Catholic philosophy of education has always paid special attention to the interpersonal relations within the educational community of the school, especially those between teachers and students. "During childhood and adolescence a student needs to experience personal relations with outstanding educators, and what is taught has greater influence on the student's formation when placed in a context of personal involvement, genuine reciprocity, coherence of attitudes, lifestyle and day to day behavior." Direct and personal contact between teachers and students is a hallmark of Catholic schools. A learning atmosphere which encourages the befriending of students is far removed from the caricature of the remote disciplinarian so cherished by the media. In measured terms the Congregation's document Lay Catholics in Schools: Witnesses to Faith describes the student-teaching relationship:

A personal relationship is always a dialogue rather than a monologue, and the teacher must be convinced that the enrichment in the relationship is mutual. But the mission must never be lost sight of: the educator can never forget that students need a companion and guide during their period of growth; they need help from others in order to overcome doubts and disorientation. Also, rapport with the students ought to be a prudent combination of familiarity and distance; and this must be adapted to the need of each individual student. Familiarity will make a personal relationship easier, but a certain distance is also needed: students need to learn how to express their own personality without being pre-conditioned; they need to be freed from inhibitions in the responsible exercise of their freedom."

Catholic schools, then, safeguard the priority of the person, both student and teacher; they foster the proper friendship between them since "an authentic formative process can only be initiated through a personal relationship."

A brief word on the school's physical environment is in order to complete this discussion on the school community. Since the school is rightly considered an extension of the home, it ought to have "some of the amenities which can create a pleasant and family atmosphere." This includes an adequate physical plant and equipment. It is especially important that this "school-home" be immediately recognizable as Catholic.

The Incarnation, which emphasizes the bodily coming of God's Son into the world, leaves its seal on every aspect of Christian life. The very fact of the Incarnation tells us that the created world is the means chosen by God through which he communicates his life to us. What is human and visible can bear the divine. If Catholic schools are to be true to their identity, they should try to suffuse their environment with this delight in the sacramental. Therefore they should express physically and visibly the external signs of Catholic culture through images, signs, symbols, icons and other objects of traditional devotion. A chapel, classroom crucifixes and statues, signage, celebrations and other sacramental reminders of Catholic ecclesial life, including good art which is not explicitly religious in its subject matter, should be evident.

4. Imbued with a Catholic Worldview

A fourth distinctive characteristic of Catholic schools, which always finds a place in the Holy See's teaching is this. Catholicism should permeate not just the class period of catechism or religious education, or the school's pastoral activities, but the entire curriculum. The Vatican documents speak of "an integral education, an education which responds to all the needs of the human person." This is why the Church establishes schools: because they are a privileged place which fosters the formation of the whole person. An integral education aims to develop gradually every capability of every student: their intellectual, physical, psychological, moral and religious dimensions. It is "intentionally directed to the growth of the whole person."

To be integral or "whole," Catholic schooling must be constantly inspired and guided by the Gospel. As we have seen, the Catholic school would betray its purpose if it failed to take as its touchstone the person of Christ and his Gospel: "It derives all the energy necessary for its educational work from him."

Because of the Gospel's vital and guiding role in a Catholic school, we might be tempted to think that the identity and distinctiveness of Catholic education lies in the quality of its religious instruction, catechesis and pastoral activities. Nothing is further from the position of the Holy See. Rather, the Catholic school is Catholic even apart from such programs and projects. It is Catholic because it undertakes to educate the whole person, addressing the requirements of his or her natural and supernatural perfection. It is integral and Catholic because it provides an education in the intellectual and moral virtues, because it prepares for a fully human life at the service of others and for the life of the world to come.

Thus, instruction should be authentically Catholic in content and methodology across the entire program of studies.

Catholicism has a particular "take" on reality that should animate its schools. It is a "comprehensive way of life" to be enshrined in the school's curriculum. One would comb in vain Vatican documents on schools to find anything about lesson planning, the order of teaching the various subjects, or the relative merit of different didactic methodologies. On the other hand, the Holy See does provide certain principles and guidelines which inspire the content of the curriculum if it is to deliver on its promise of offering students an integral education. Let's look at two of these: the principle of truth and the integration of faith, culture and life.

4.1 Search for Wisdom and Truth

In an age of information overload, Catholic schools must be especially attentive to the delicate balance between human experience and understanding. In the words of T.S. Eliot, we do not want our students to say: "We had the experience but missed the meaning."

On the other hand, knowledge and understanding are far more than the accumulation of information. Again T.S. Eliot puts it just right: "Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge? Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?" Catholic schools do far more than convey information to passive students. They aspire to teach wisdom, habituating their students "to desire learning so much that he or she will delight in becoming a self-learner."

Intrinsically related to the search for wisdom is another idea frequently repeated in Vatican teaching: the confidence expressed that the human, however limited its powers, has the capacity to come to the knowledge of truth. This conviction about the nature of truth is too important to be confused about in Catholic schooling. Unlike skeptics and relativists, Catholic teachers share a specific conviction about truth: that they can pursue, and, to a limited but real extent, attain and communicate it to others. Catholic schools take up the daunting task of freeing boys and girls from the insidious consequences of what Benedict XVI recently called the "dictatorship of relativism" – a dictatorship which cripples all genuine education. Catholic educators are to have in themselves and develop in others a passion for truth which defeats moral and cultural relativism. They are to Educate "in the truth."

In an ad limina address to a group of American bishops, Pope John Paul II pinpointed the importance of a correct grasp of truth if the Church's educational efforts are to bear fruit:

The greatest challenge to Catholic education in the United States today, and the greatest contribution that authentically Catholic education can make to American culture, is to restore to that culture the conviction that human beings can grasp the truth of things, and in grasping that truth can know their duties to God, to themselves and their neighbors. In meeting that challenge, the Catholic educator will hear an echo of Christ's words: "If you continue in my word, you are truly my disciples, and you will know the truth, and the truth will make you free" (Jn 8:32). The contemporary world urgently needs the service of educational institutions which uphold and teach that truth is "that fundamental value without which freedom, justice and human dignity are extinguished" (Veritatis Splendor, 4).

Closely following papal teaching, the Holy See's documents on schools insist on the principle that education is about discovering truth both in its natural and supernatural dimensions: "The school considers human knowledge as a truth to be discovered. In the measure in which subjects are taught by someone who knowingly and without restraint seeks the truth, they are to that extent Christian. Discovery and awareness of truth leads man to the discovery of Truth itself."

For the most part, Catholic schools conform to required curricula, but they implement their programs within an overall religious perspective. This perspective includes criteria such as "confidence in our ability to attain truth, at least in a limited way – a confidence based not on feeling but on faith . . . [and] the ability to make judgments about what is true and what is false." Convictions about truth are at home in authentically Catholic schools.

4.2 Faith, Culture and Life

A second principle governing all Catholic education from the apostolic age down to the present is the notion that the faithful should be engaged in transforming culture in light of the Gospel. Schools prepare students to relate the Catholic faith to their particular culture and to live that faith in practice. In its 1997 document, the Congregation for Catholic Education commented:

From the nature of the Catholic school also stems one of the most significant elements of its educational project: the synthesis of culture and faith. The endeavor to interweave reason and faith, which has become the heart of individual subjects, makes for unity, articulation and coordination, bringing forth within what is learnt in a school a Christian vision of the world, of life, of culture and of history. Schools form students within their own culture for which they teach an appreciation of its positive elements and strive to help them foster the further inculturation of the Gospel in their own situation. Yet they must also, when appropriate according to the students' age, be critical and evaluative. It is the Catholic faith which provides Catholic educators with the essential principles for critique and evaluation. Faith and culture are intimately related, and students should be led, in ways suitable to their level of intellectual development, to grasp the importance of this relationship. "We must always remember that, while faith is not to be identified with any one culture and is independent of all cultures, it must inspire every culture."

The educational philosophy guiding a Catholic school also seeks to be a place where "faith, culture and life are brought into harmony." Central to the Catholic school is its mission of holiness, of saint making. Mindful of redemption in Christ, the Catholic school aims at forming in its pupils those particular virtues that will enable them to live a new life in Christ and help them to play faithfully their part in building up the kingdom of God. It strives to develop virtue "by the integration of culture with faith and of faith with living." Taking the risk of being blunt, the Congregation for Catholic Education has written that "the Catholic school tries to create within its walls a climate in which the pupil's faith will gradually mature and enable him to assume the responsibility placed on him by Baptism."

A primary, but hardly only, way of guiding students to becoming committed Catholics, as we have discussed in emphasizing the importance of an integrated curriculum, is providing solid religious instruction. To be sure, "education in the faith is a part of the finality of a Catholic school." For young Catholics, such instruction embraces both knowledge of the faith and fostering its practice. Still, we must always take special care to avoid thinking that a Catholic school's distinctiveness rests solely on the shoulders of its religious education program. Such a position fosters the misunderstanding that faith and life are divorced, that religion is a merely private affair with neither a specific content nor moral obligations.

5. Sustained by the Witness of Teaching

Lastly I would like to close with a few observations about the vital role teachers play in ensuring a school's Catholic identity. With them lies the primary responsibility for creating a unique Christian school climate, as individuals and as a community. Indeed, "it depends chiefly on them whether the Catholic school achieves its purpose." Consequently the Holy See's documents pay considerable attention to the vocation of teachers and their specific participation in the Church's mission. Theirs is a calling and not simply the exercise of a profession.

In a word, those involved in Catholic schools, with very few exceptions, should be practising Catholics committed to the Church and living her sacramental life. Despite the difficulties involved – which you know all too well – it is, I believe, a serious mistake to be anything other than "rigorists" about the personnel hired. The Catholic school system in Ontario, Canada, where I was raised, when pressured by public authorities for what they regarded as reasonable accommodations, relaxed this requirement for a time. The result was disastrous. With the influx of non-Catholic teachers, many schools ended up by seriously compromising their Catholic identity. Children absorbed, even if they were not taught, a soft indifferentism which sustained neither their practice of the faith nor their ability to imbue society with authentically Christian values. Principals, pastors, trustees and parents share, therefore, in the serious duty of hiring teachers who meet the standards of doctrine and integrity of life essential to maintaining and advancing a school's Catholic identity.

We need teachers with a clear and precise understanding of the specific nature and role of Catholic education. The careful hiring of men and women who enthusiastically endorse a Catholic ethos is, I would maintain, the primary way to foster a school's catholicity. The reason for such concern about teachers is straightforward. Catholic education is strengthened by its "martyrs." Like the early Church, it is built up through the shedding of their blood. Those of us who are, or have been, teachers know all about that. But I am speaking here about "martyrs" in the original sense of "witnesses."

As well as fostering a Catholic view across throughout the curriculum, even in so-called secular subjects, "if students in Catholic schools are to gain a genuine experience of the Church, the example of teachers and others responsible for their formation is crucial: the witness of adults in the school community is a vital part of the school's identity." Children will pick up far more by example than by masterful pedagogical techniques, especially in the practice of Christian virtues.

Educators at every level in the Church are expected to be models for their students by bearing transparent witness to the Gospel. If boys and girls are to experience the splendor of the Church, the Christian example of teachers and others responsible for their formation is crucial.

The prophetic words of Pope Paul VI ring as true today as they did thirty years ago: "Modern man listens more willingly to witnesses than to teachers, and if he does listen to teachers, it is because they are witnesses." What teachers do and how they act are more significant than what they say – inside and outside the classroom. That's how the Church evangelizes. "The more completely an educator can give concrete witness to the model of the ideal person [Christ] that is being presented to the students, the more this ideal will be believed and imitated." Hypocrisy particularly turns off today's students. While their demands are high, perhaps sometimes even unreasonably so, there is no avoiding the fact that if teachers fail to model fidelity to the truth and virtuous behavior, then even the best of curricula cannot successfully embody a Catholic school's distinctive ethos.

Conclusion

In conclusion, I would like to repeat what, I hope, has become obvious. The Holy See, through its documents and interventions, whether of the Pope or of other Vatican offices, sees in Catholic schools an enormous heritage and an indispensable instrument in carrying out the Church's mission in the third Christian millennium. Ensuring their genuinely Catholic identity is the Church's greatest challenge. Complementing the irreplaceable role of parents in ensuring the education of their children, such schools, which should be available to all, build up the community of believers, evangelize culture and serve the common good of society.

I would also like to commend your interest in promoting authentically Catholic schools, especially for those of limited economic means. Yours is a daunting task. May the Lord who began this good work in you bring it to completion!

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Archbishop J. Michael Miller, C.S.B. "The Holy Sees Teaching On Catholic Schools." The Catholic University of America (Sept. 14, 2005).

Given at the Solidarity Association, Washington D.C., 14 September 2005.

The Author

The Most Reverend J. Michael Miller, CSB, was born in Ottawa, Canada, on July 9, 1946. On June 29, 1975, Pope Paul VI ordained him a priest, and on November 23, 2003 Pope John Paul II appointed him titular Archbishop of Vertara, Secretary of the Congregation for Catholic Education and Vice President of the Pontifical Work of Priestly Vocations. He became Archbishop of Vancouver on January 2, 2009. Archbishop Miller is a member of the Pontifical Committee for International Eucharistic Congresses and of the Pontifical Council for Pastoral Care of Migrants and Itinerant People as well as a consultor to the Congregation for Bishops.

The Most Reverend J. Michael Miller, CSB, was born in Ottawa, Canada, on July 9, 1946. On June 29, 1975, Pope Paul VI ordained him a priest, and on November 23, 2003 Pope John Paul II appointed him titular Archbishop of Vertara, Secretary of the Congregation for Catholic Education and Vice President of the Pontifical Work of Priestly Vocations. He became Archbishop of Vancouver on January 2, 2009. Archbishop Miller is a member of the Pontifical Committee for International Eucharistic Congresses and of the Pontifical Council for Pastoral Care of Migrants and Itinerant People as well as a consultor to the Congregation for Bishops.

Archbishop Miller is a specialist on the papacy and modern papal teaching, he has published seven books and more than 100 articles, scholarly, popular and journalistic. His books include The Shepherd and the Rock: Origins, Development, and Mission of the Papacy the Encyclicals of John Paul II, and The Holy See's Teaching on Catholic Schools.

Copyright © 2005 Archbishop J. Michael Miller, C.S.B