Proudly Pro-Choice on Education

- MARY ANASTASIA O'GRADY

New York's archbishop on schools and the challenges facing the Catholic Church.

|

"The child is not a mere creature of the state. Parents have the primary responsibility to see how and where their children are educated."

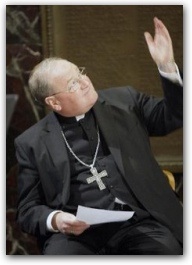

For thousands of lower-income New York children caught in the city's failing public school system, any high-profile advocate for choice in education might seem to be heaven-sent. Perhaps this one is. His name is Archbishop Timothy Dolan, the newly appointed spiritual leader of New York's 2.5 million Catholics.

When I went to see Archbishop Dolan early on a midweek morning last month at the New York Catholic Center in Manhattan, his warm and gregarious personality had already been widely reported on. His beaming -- and may I say prominently Irish -- face had been plastered all over the front pages of local newspapers and on the evening news. We had learned early on that he believes in being a joyful shepherd, that he is an outspoken opponent of gay marriage and abortion, and that he likes baseball -- though he told me, with a roaring laugh, that he is "pro-choice when it comes to Mets or Yankees."

Yet the early press coverage leaves a lot of unanswered questions about what to expect from this 59-year-old St. Louis native, who inherits not only substantial political, cultural and religious influence in the largest city in the nation but also a lot of challenges. The Roman Catholic Church has long been an important part of the civic fabric of New York. But in recent decades the trends have not been good. Catholic schools have been closing down, young people have been drifting from the faith, and fewer young men and women are entering Catholic Church vocations. What does this optimistic archbishop have up his sleeve?

The issue that most New Yorkers, Catholic or not, may be interested in is whether the diocese's 279 Catholic schools -- an educational lifeline to over 88,000 children -- can survive. More than 50 have closed down in the past 25 years, and those that are left often struggle to get by. Surely they would have a better chance if New York had an education voucher program like Milwaukee does? So I began our conversation by asking the archbishop to talk about the Milwaukee experience. His already radiant face brightened even more.

"We called it Choice in Education and it was a genuine blessing," he says, sitting up in his chair and leaning forward. "It began under Gov. Tommy Thompson, and the idea was that parents would have a choice as to where they would send their children. It was restricted in that it was just the city of Milwaukee, and the parents had to be under a certain income level. But it was so successful" he explains, that demand soon exceeded the cap of 15,000 students.

When that happened, Milwaukeeans wanted to go further. Archbishop Dolan says he was "part of a coalition, two years ago, that worked with Gov. [Jim] Doyle to expand the cap to 22,000 students." As of now it serves about 20,000 children of families that meet strict income limits. "It's been a tremendous boost," he says, smiling enthusiastically.

"I met someone a week or so ago who said if you ask me my religion I'd probably say I am an atheist, but I love Catholic schools because they do such a sterling job and I am going to support them." |

The archbishop says that "philosophically," as much as practically, the Milwaukee diocese celebrated the voucher program. "The Catholic Church has always been an ardent advocate for parental rights in education," he points out. "The experiment is now about 15 years old, and it is applauded by all sides . . . except," he notes in a more somber tone, "there [are] some who would attack it, particularly those associated with the public-school teachers lobby, which is very strong in Wisconsin. They still apparently believe that the government should have a monopoly on education."

Despite the power of that lobby, the archbishop says "the parents and the wider community appreciate [the voucher program]," and he stresses that it is popular with more than just Catholics. "The coalition that supports it is made up of, yes, Catholics, but also many Jewish leaders, civic leaders, many politicians, people who just love and support the community with no religious background at all. There seemed to be a widespread appreciation that this was a tremendous boost to the Milwaukee community, and of course we're always hoping to expand it."

Yet what has been possible in Milwaukee may not be in New York. "The challenge of keeping our wonderful Catholic schools strong, affordable, accessible and available," the archbishop says, is "all the more pressing here in New York because we don't have the blessing of vouchers." His next comment suggests that he doesn't expect them here anytime soon. "I know that the state of New York likes to consider itself kind of on the vanguard of enlightened progressive initiatives, but in this regard Wisconsin is way ahead."

Still, the archbishop is not deterred. After all, he reminds me, one of the greatest New York archbishops of all time, John Hughes, had a similar problem. "He got into a battle in the 1840s with what was called then the New York Public School Society, saying 'I'd like a portion of those [government] funds to educate our children.'" He lost that fight but went on to build the city's Catholic school system, which educated masses of Irish immigrants previously considered impossibly ignorant and unruly.

Hughes was continually short of funds, as the diocese is today, but Archbishop Dolan says this too can be kind of a blessing. "It's why the Catholic schools are scrappy," he says. "And in a way that's part of the genius of our schools: We are not rolling in dough. We have to fight for every dime; it becomes a communal endeavor. There is a sense of pride and ownership among the people because, darn it, we fought for this school, we love it, we scraped for it, we have mopped floors and painted classrooms, and we do not take this for granted."

When I rattle off some of the dropping enrollment statistics in the diocese, the archbishop admits that the "schools can really cause us to go for the Maalox and Tylenol. But," he says, "what we have to ask ourselves is 'Are they worth it?' And we say you bet they are. They're worth it because nobody does it better than the [Catholic] Church when it comes to education."

The archbishop admits that at times others in the Catholic Church don't share his enthusiasm. "Some priests and some bishops have lost their nerve when it comes to Catholic schools. [They've] almost said, 'boy they were nice and we'll do our best to keep the ones that we got but more or less they are on life support and I guess in 50 years they're going to fade away.'" The archbishop says his predecessor Cardinal Egan rejected this line of thinking and he does too. "Its time for us bishops to say: these . . . are . . . worth . . . fighting . . . for," he says, emphasizing each word slowly. "These are worth putting at the top of our agenda, and these are worth something not only internally for us as a church as we pass on the faith for our kids and grandkids, but it is also a highly regarded public service that we do for the wider community. And darn it we do it well, we have a great tradition of it and we're not going to stand by and see it collapse."

"And in a way that's part of the genius of our schools: We are not rolling in dough. We have to fight for every dime; it becomes a communal endeavor. There is a sense of pride and ownership among the people because, darn it, we fought for this school, we love it, we scraped for it, we have mopped floors and painted classrooms, and we do not take this for granted." |

So what's the plan? The archbishop, who seems to me part theologian, part historian, and part marketing guru, is already thinking about ways to explore and expand private funding initiatives such as the successful Inner City Scholarship Fund.

He is sure that there can be "wider participation from New York's philanthropic, business and civic community." There are many "who so love the New York community" and see education as "one of the finest investments we can make in the future of our community." Often, he says, givers are not Catholic. "I met someone a week or so ago who said if you ask me my religion I'd probably say I am an atheist, but I love Catholic schools because they do such a sterling job and I am going to support them."

If Archbishop Dolan can save and perhaps even revive the city's Catholic school system, he will be a hero to all of New York. But while he's working on that, he has two other problems that are troubling for the Catholic Church. The first is the growing number of 20- and 30-somethings, raised in the faith, who are not attending Mass or getting married in the Catholic Church. The second is the sharp drop in people choosing Catholic Church vocations.

I asked him what he thinks has gone wrong. For starters, he says, the Catholic Church for too long took for granted the Catholic culture, "when it was presumed that you would go to Sunday Mass, that you would marry a Catholic and be married in the Catholic Church, when it was presumed that you would always remain in the faith, with tons of priests and nuns and Catholic schools to serve you."

Those days are gone, and now he says its time to "recover the evangelizing muscle that characterized the early church." This means putting an end to the "wavering" that has too often characterized the Catholic Church since the Second Vatican Council and a return to a clear and confident message.

"Very often even the word Catholic even the word church has had a question mark behind it," he says. "Does it know where it's going? Does it know what its teaching? Is it going to be around? There was a big question mark. A young person will not give his or her life for a question mark. A young person will give his or her life for an exclamation point."

This "recovery" in confidence, he says, began under John Paul II and continues under Pope Benedict XVI. In his new role, Archbishop Dolan intends to keep it going. Being a Catholic is an "adventure in fidelity," he insists. The Catholic Church, he says, has "a very compelling moral message. She calls us to what is most noble in our human makeup, dares us to become saints, challenges us to heroic virtue."

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Mary Anastasia O'Grady. "Proudly Pro-Choice on Education." The Wall Street Journal (May 11, 2009).

Reprinted with permission of the author and The Wall Street Journal © 2009 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

The Author

Mary Anastasia O'Grady is an editor of the Wall Street Journal and member of the Wall Street Journal Editorial Board since 2005. She writes predominately on Latin America.

Copyright © 2009 Wall Street Journal