Richard Strauss: the Bavarian Joker in the Pack

- PAUL JOHNSON

Richard Strauss died 60 years ago this year. Not only is he one of my top ten favourite composers, he is also the one I would most like to be cast away with on an island so that I could pluck out the heart of his mystery.

|

|

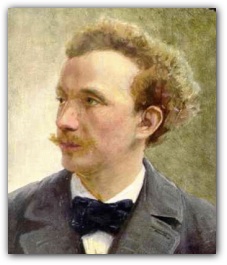

Richard Strauss

1864-1949 |

His subtleties are infinite, especially his constant, minute innovations, always designed to improve existing models but rejecting crude revolutions, so noisily intrusive in his time. I would like to explore his early works, like the tone poem Macbeth and his symphonies, Brahmsian exercises never performed today, and get to know all his operas including the weird Guntram (1892) and his last great masterpiece Capriccio, written 60 years later.

But plucking that complex heart requires a knowledge of German. I recall the first time I saw Rosenkavalier, at the East Berlin opera house in 1955. It has since become one of the four works I regard as perfect musical plays, alongside Figaro, Carmen and La Bohème, and I relished it enormously at the time. But my next-door neighbour at the performance, old Birley, Eton headmaster and a notable Germanophile, said: "Oh, but to enjoy this delicious piece you must know German very well, to follow the slang, literary allusions and sheer comic devilry of the Marschallin's lines, written by that genius Hugo Von Hofmannstal, and set to music perfectly by Strauss, who was fonder of a joke than any other composer." (Indeed there is a famous joke in the last ten bars of the opera when the black page, Mohammed, returns to pick up the handkerchief.) Birley added: "Oddly enough, though they collaborated perfectly, Strauss hardly ever met his best librettist. They did it all by correspondence, much the best way. Strauss thought him too domineering."

It was Strauss's fate to be pushed about by bullies all his life. Tall, gangling, easy-going, loving to laugh while he drank his mother's beer (she was a Pilsner heiress called Josie Pschorr) or playing an interminable card game called Skat, he was a child prodigy. Like Mozart, he was masterminded by his father, Franz, who played first horn in the Munich Court Orchestra for half a century. It was bossy Franz who wrote, or rewrote Siegfried's famous horn-call. But he detested Wagner as a person (who didn't?) and as a composer, and forbade the boy Richard to have anything to do with his music. Or anyone else's after Beethoven. So the teenage boy had to read the full orchestral score of Tristan and Brahms's Fourth by candlelight in the secrecy of his bedroom. Still, his old man was useful in getting the members of his band to teach his son all they knew.

Like his great contemporary Elgar, Strauss, in addition to playing the piano and the violin up to concert standard, could have a shot at every instrument, and this was one reason why his orchestration is so magnificent, even better than Elgar's in fact, and more pleasing than the sounds created by his other great contemporary, Mahler. Like Mahler, Strauss became a hugely proficient conductor, and this enabled him to know exactly how far he could go in setting an orchestra impossible tasks in state-of-the-art playing. (It was not unknown, however, for musicians to refuse to play his stuff.)

Perhaps Strauss liked to be bossed about because he replaced his dominant dad with an even more forceful wife. Pauline de Ahna was a fine professional soprano, and she helped him to become the composer who wrote most cleverly and sympathetically for the high female voice. (It is no accident that Rosenkavalier has three star sopranos). He must have loved her because his wedding present to her was the four songs of Opus 27, including those two delights, "Morgen" and "Ruhe". And she was still looking over his shoulder when, aged 83, he composed his famous "Vier letzte Lieder" in 1948. But she was horribly bossy. Not for nothing was she the daughter of a Bavarian general, a tough Marshallin by birth. They fought and screamed at each other, having exchanges which, as he put it, "I ought to set to music." My old friend Philip Hope-Wallace, who collected anecdotes, real and apocryphal, about outrageous prima donnas, delighted to recount that Pauline had a special baton made and, when they rowed, would belabour Strauss with it, shouting "I'll conduct you, you scoundrel." She accused him, usually falsely, of having affairs with blonde pieces of fluff he picked out of the chorus, and threatening to leave, but could always be put back into a good temper by Strauss writing her a jokey song.

|

He was a modest man: "I may not be a first-rate composer, but I am a first-class second-rate composer." |

No one ever made more musical jokes than Strauss, and good ones too, from bleating sheep to the use of a wind-machine in Ein Heldenleben. Musicians can be divided, broadly, into two classes: those who think Beethoven the greatest composer, highly serious people, often humourless and apocalyptic, and those who take things more lightly and prefer Mozart. Strauss was emphatically a Mozartian. That was all very well in the joyous, dancing and frivolous years before the first world war spoiled everything in Europe, for ever. At that time Strauss was the most successful composer in the world, beating even Puccini, and many regarded him as the best. But after the horrors of the war he fell from favour and never really recovered. The north German intellectuals, in Hamburg and Berlin, and the trend-setting Saxon nobs in snooty Dresden, thought him unserious. Why didn't he write symphonies like Brahms or go modern like Hindemith or Webern? The jokes were in deplorable taste, and was it true that in the United States he had conducted a concert in a department store, just to make money? It was Strauss's fate to be subjected to vicious attacks all his life for one reason or another. After the second world war, Bruno Walter and others accused him of kowtowing to Hitler. It is true he was terrified that his son, who was married to a Jewess, would be packed off to a camp with his wife.

He was also accused, always, of being "a lazy Bavarian". This charge, at least, can be refuted by the evidence of his work, great in quantity and still more in quality. He was a modest man: "I may not be a first-rate composer, but I am a first-class second-rate composer." (This recalls Verdi's famous saying, "I am not a great composer but I am certainly a very experienced one.") Lazy, Strauss was not. He regularly worked a 12-hour day. Close examination of his autograph manuscripts tell a revealing tale of fluent intensity and energy, reminding one of Dickens's frenzied holographs, or the magical drawings and oil-sketches of Ingres. All three were men of genius who never relaxed for a second when at work. Strauss was a master of the cantilena, the long, sustained vocal line, and this reached its epitome in his "Four Last Songs", his astonishing octogenarian masterpiece, which delights the experts and is loved by millions, especially in the celebrated recording by Lisa della Casa. So, good for the old Joker, say I.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Paul Johnson. "Richard Strauss: the Bavarian Joker in the Pack." The Spectator (March 25, 2009).

This article is from Paul Johnson's "And another thing" column for The Spectator and is reprinted with permission of the author.

The Author