Remembering Oriana

- PATRICK LUCIANI

Today, Oriana Fallaci would have celebrated her 78th birthday.

|

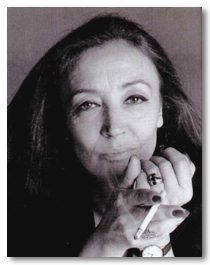

Oriana Fallaci

1929-2006 |

When she died last September, she was given a modest funeral attended only by a few, including her nephews, her surviving sister and her long-time friend Franco Zeffirelli, the film director. But when I last saw her in New York, she admitted wanting a state funeral with full military honours; she saw herself as a soldier fighting tyranny to her last breath. That is highly unlikely under the centre-left Italian government of Romano Prodi.

I first met Fallaci last year after I wrote to her. I was surprised when she called early one Saturday morning, but I soon found out that “La Fallaci”—as she called herself—usually did everything for herself despite fighting a cancer for years that left her weak and exhausted. We struck up a friendship, talking frequently on the phone, mostly about her latest book, The Force of Reason, the last in a trilogy on her reaction to 9/11 and the rise of radical Islam. I visited her twice at her home in Manhattan. The stairs in her three-storey brownstone always left her breathless. Her stubborn pride stood in the way of most offers of help. Assistants dispatched by her publisher—often sent packing—had a hard time with her temper and high standards. And she refused all home care. “Only Fallaci takes care of Fallaci”, she told me.

Through her illness she kept writing. But after 9/11, she pulled herself out of a voluntary exile—and in the middle of a novel—to fight a fascism she immediately recognized from her childhood. In her living room she kept a silver-framed anti-fascist lecture from 1933 at the Irving Plaza Hotel, next to a famous portrait of herself by Francesco Scavullo. But she saved her real venom for the “cicadas,” as she called them, the politically correct academics, intellectuals and journalists who made excuses for the inexcusable. She started her life fighting Italian fascism as a young girl with the partisans in Tuscany, and ended it fighting another tyranny when she died in a clinic in her beloved Florence. She was fond of saying that these “cicadas” only see tyranny if it comes from the right. “And forget the nonsense that these terrorists are fighting for the poor. Look and you’ll see they are educated and come from prosperous families like the children of the Red Brigade.”

When we first met in February, 2006, I could hardly believe that this tiny woman was the great Fallaci who had intimidated some of the world’s most powerful leaders. She insisted on making me lunch, two prosciutto and cheese sandwiches with wine. “My motherly instincts come out when someone hasn’t eaten.” She seemed happiest when rummaging around in the kitchen preparing dinner, taking pride in explaining all the ingredients. “This is the wonderful white truffle from Sardinia, not the black ones from Tuscany.” Once she made a special trip to the butchers to pick out a fine cut of beef; she assumed I liked anchovies because of the region of Italy my family came from and quickly put them into a tomato salad.

When we first met in February, 2006, I could hardly believe that this tiny woman was the great Fallaci who had intimidated some of the world’s most powerful leaders. |

Failure of any kind bothered her to distraction. Though her books sold in the millions, she was obsessed with one bookstore in San Francisco that banned her book. And she was delighted to hear that her last book was doing well in Canada. Despite failing eyesight, she struggled to read each and every review. She wanted everyone to read her, but she was pleased most of all when bakers and cabdrivers bought her books: “My mother always told me to write for the people, and I have always tried to keep that promise.” Despite her indictment by an Italian judge in Bergamo for “vilifying Islam”—a charge levelled by an Italian Muslim convert—she dared the courts to jail her. Her popularity in Italy was such that a political movement wanted to name their party after her, something she managed to stop, she told me, only through court action.

Despite her love of her homeland and its language, she exiled herself to New York City following in the footsteps of other great Italians including Giuseppe Garibaldi and Arturo Toscanini. She even saw herself following the greatest of all exiles in Italian history, Dante Alighieri. New York always played a large role in her imagination as a place where she wanted to live and write; in a country she admired immensely for its founding principles of liberty and equality. And she loved the English language, admiring the writing of Hemingway and Joseph Conrad. But her love of homeland wasn’t reciprocated. She received a series of insults and calumnies she never forgave or forgot. Only in the last year of her life did a number of Italian awards come her way. And although she was dismissive of them, I couldn’t help thinking she was grateful nonetheless.

When she ended her self-imposed silence, she entered the public debate on Islam in a fury with a startling series of long articles in the Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera. They were quickly published under the title The Rage and the Pride. The book quickly became a publishing sensation. It sold 200,000 copies on the first day it appeared in bookstores. People lined up, and the shelves were cleared as soon as they were stocked. In the end, the book sold over one and a half million copies in Europe.

Her mission was to complete her trilogy on Islamism before she died, ending with The Force of Reason. I’ve come to believe that her work kept her alive long enough to warn the West of what was to come. Yet she had little faith that the West could defend itself. “ Rome fell not because of its enemies outside; it was destroyed from within.” Fallaci feared the West had given up its principles. “When you laugh at your history and your culture, you are finished.” She was particularity disdainful of Italians who seemed interested only in soccer.

In an interview with Christopher Hitchens in last December’s Vanity Fair, he was disappointed that she wouldn’t reveal any information about her meeting with Pope Benedict in the year before her death, perhaps her greatest interview of all. She did confide that she kept in touch with the Pope and that they occasionally exchanged pieces of music. |

She called herself a Christian atheist or a cultural Roman Catholic. Nothing would have surprised her about the reaction in the Muslim world to Pope Benedict’s statement about the Prophet Muhammad and the violence that followed. Fallaci always mocked the notion of a Euro-Islamic “dialogue.” At our first visit she read me a long chapter she had written about the murder of a priest in Turkey after the Muhammad cartoon affair.

In an interview with Christopher Hitchens in last December’s Vanity Fair, he was disappointed that she wouldn’t reveal any information about her meeting with Pope Benedict in the year before her death, perhaps her greatest interview of all. She did confide that she kept in touch with the Pope and that they occasionally exchanged pieces of music. Regarding the conflict with Islam, Fallaci was convinced she and the Pope were in total agreement. Her respect for Ratzinger may partly explain why she donated her papers to the Pontifical Lateran University.

But she wasn’t shy about criticizing the actions of Pope John Paul II and his apologies to the Muslim world for the Crusades, among other sins, in 2000. “Let them, the sons of Allah”—as she called Muslims—“apologize for the thousands of Italians they enslaved in the Barbary raids.”

On other matters, she was free with her opinions, outrages and regrets. In the ’60s she was against the Vietnam War, but came to see the U.S. was more right than wrong. This led to a shouting match with Jane Fonda in the streets of Paris. She also stared down two of Muhammad Ali’s bodyguards, who followed her to her car after she stormed out of an interview at his home in Louisville, KY, when she threw a microphone at Ali who mocked her questions. Of all the leaders she interviewed, she most admired Indira Gandhi and Golda Meir. She struck up a deep friendship with Meir, and once helped her with her makeup and lent her a pearl necklace for a TV interview. Although an admirer of Condoleezza Rice—whom she called Condolcenza—she was livid when the U.S. pressed the Europeans to accept Turkey into the European Union.

Lifetime habits were hard to break: she continued to enjoy her cigarettes (Ben Sherman lights) to the very end, leaving a trail of ashes in her brownstone. The only drink that her 80-pound frame could tolerate was an occasional sip of Baileys. But she took vicarious pleasure in others enjoying her wines and champagne. Through her illness, she maintained her dignity with exquisite taste, tailored skirts and understated Italian leather slippers and a simple pearl necklace.

I found her unpretentious and quick to anger, letting out a stream of Italian invectives for her foes—“they are all cretins”—that made me laugh out loud, but she could just as quickly become warm, generous and sentimental. She did most of the talking. She once called just to apologize for having taken out on me her anger about the madness around her. I suspect she spoke to everyone in the same manner, whether heads of state or cab drivers. And in old European fashion, she called everyone “dahlin’.”

Almost the only regret she admitted was not pursuing a political career; another stunning admission—which would come as a shock to Kissinger, the Shah of Iran, Muammar Kadafi, Ayatollah Khomeini, Yasser Arafat and other world leaders she interviewed without mercy in the ’70s—was that she wasn’t forceful enough in life. This flash of insecurity caught me by surprise and we talked about it at length.

She never married and had no children. The last time I saw her was for dinner at her home a year ago. As I left that night, I helped her take her recyclables to the curb. As she closed the iron shutter gate, I could only think of her slow and painful climb back up the stairs.

She chose an independent life dedicated to writing right to the end with courage and an unrelenting resolve. To the end, only Fallaci took care of Fallaci.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Patrick Luciani, "Remembering Oriana." National Post, (Canada) June 29, 2007.

Reprinted with permission of the National Post.

The Author

Patrick Luciani is co-director of the Salon Speakers Series at Grano in Toronto, and a member at Massey College.

Copyright © 2007 National Post