The Catholicism of William Shakespeare

- JOSEPH PEARCE

Ample evidence supports the claim that the Bard of Avon was a lifelong Catholic.

This year, we have been commemorating the 400th anniversary of the death of one of the world's greatest writers, William Shakespeare (1564-1616). For those who have long admired his brilliance and Christian imagination, the evidence that he was a believing Catholic in a time of persecution is very exciting.

This year, we have been commemorating the 400th anniversary of the death of one of the world's greatest writers, William Shakespeare (1564-1616). For those who have long admired his brilliance and Christian imagination, the evidence that he was a believing Catholic in a time of persecution is very exciting.

Broadly speaking, the evidence for Shakespeare's Catholicism is biographical, historical and textual. The biographical and historical evidence is found in the documented facts of his life and of the turbulent times in which he lived, and his plays and poems offer further, textual evidence of his Catholic convictions.

Passing on the faith

Born in 1564 in Stratfordupon- Avon, England, Shakespeare lived at a time when the practice of Catholicism was illegal. In 1534, King Henry VIII had declared that he and his successors would lead a statecontrolled church and that only this state-imposed religion would be tolerated. Priests were tortured and put to death, as were those who tried to hide them from the tyrannical government. Recusants — those who refused to attend the services of the state religion — were fined heavily.

Shakespeare's mother's family, the Ardens, were among the most famous recusants in the whole of England. Shakespeare's father, John, was fined for his recusancy in 1592 and had retired from his career in politics rather than swear allegiance to the state religion. Several scholars, most notably John Henry de Groot, have detailed the evidence for John Shakespeare's Catholicism, including the fact that he signed a "testament" to his Catholic faith, which had been written by St. Charles Borromeo and was probably smuggled into England by Jesuit missionaries. As for Shakespeare himself, evidence suggests that he remained a Catholic throughout his life.

Shakespeare's mother's family, the Ardens, were among the most famous recusants in the whole of England. Shakespeare's father, John, was fined for his recusancy in 1592 and had retired from his career in politics rather than swear allegiance to the state religion.

During Shakespeare's youth, the religion of the nation was far from a settled question. In 1568, when he was only 4 years old, Mary, Queen of Scots, fled to England, raising hopes of an eventual Catholic succession. These hopes were then dashed by Mary's imprisonment on the orders of Queen Elizabeth I. The Northern Rebellion, led by the Duke of Norfolk and the Earl of Northumberland in support of Mary, was crushed ruthlessly the following year. More than 800 rebels — mainly Catholics — were executed. Several scholars have suggested that the Northern Rebellion inspired Shakespeare's two-part Henry IV.

There has been much scholarly debate about what Shakespeare was doing as a young man between 1578 and 1582, the so-called "lost years" prior to his marriage to Anne Hathaway. According to John Aubrey, one of the earliest sources available, Shakespeare "had been in his younger years a schoolmaster in the country." Scholars including E.A.J. Honigmann, J. Dover Wilson and Stephen Greenblatt have found evidence that Shakespeare might have spent time at Hoghton Tower, a recusant household in Lancashire. In that case, he would likely have met the Jesuit martyr St. Edmund Campion shortly before Campion's arrest in June 1581 and subsequent execution.

Having returned to Stratford, where he married and had three children with his wife, Anne, it seems that Shakespeare was forced to leave his hometown. Scholars such as Heinrich Mutschmann and Karl Wentersdorf (Shakespeare and Catholicism, 1952) have demonstrated that a vendetta was directed against him by Sir Thomas Lucy, the local lord of the manor. As Queen Elizabeth's chief Protestant agent in the area, Lucy led searches of local Catholic houses, including very probably Shakespeare's own home.

In May 1606, Shakespeare's daughter, Susanna, appeared on a list of recusants brought before Stratford's church court. This fact, discovered in 1964, signifies that Catholicism had been passed from one generation of the family to the next, further suggesting that Shakespeare himself had remained a Catholic throughout his life.

Martyrs and 'God's spies'

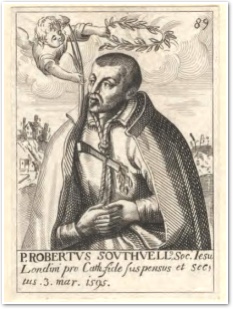

After his arrival in London, Shakespeare enjoyed the patronage of the Earl of Southampton, a known Catholic who seems to have had Jesuit martyr St. Robert Southwell as his confessor. Shakespeare likely knew the Jesuit priest prior to the latter's arrest in 1592, the year in which Shakespeare's father was fined for being a recusant. In fact, there are many allusions to Southwell in Shakespeare's plays.

Serveal of Shakespeare's plays allude to the Jesuit

Serveal of Shakespeare's plays allude to the Jesuit martyr St. Robert Southwell, depicted in this line

engraving originally published in 1608.

A thorough discussion of the plentiful textual evidence for Shakespeare's Catholicism in his plays and poems is not possible in this brief survey. Here are just a couple examples.

Southwell wrote a poem titled Decease Release about the execution of Mary, Queen of Scots, whom many Catholics believed to be a martyr for the faith. In the poem, written from the queen's viewpoint, Southwell casts her as "pounded spice," the fragrance of which ascends to heaven: "God's spice I was and pounding was my due."

Although the poem was clearly Southwell's tribute to the executed queen, its first-person voice gave it added potency following Southwell's own martyrdom in 1595, toward the beginning of Shakespeare's career. Like the queen of whom he wrote, Southwell was also "pounded spice" or "God's spice," whose essence is more pleasing and valued for being crushed.

As Southwell's ghostly presence can be observed throughout The Merchant of Venice, one can read Portia's beautiful "quality of mercy" speech as a plea to Queen Elizabeth to show the Jesuits mercy.

In King Lear (1605), the title character's use of the phrase "God's spies" is a clear punning reference to "God's spice." It is also a veiled reference to Jesuits, such as Southwell, who though "traitors" in the eyes of the Elizabethan and Jacobean state were "God's spies." They, too, became "God's spice," ground to death that they might receive their martyr's reward in heaven. "Upon such sacrifices," Lear tells Cordelia, "the gods themselves throw incense."

Romeo and Juliet and The Merchant of Venice were written in the same year in which Southwell was martyred, and both plays contain symbolically charged references to the Jesuit's life and work. In the latter play, for instance, several scholars have suggested that Antonio is a thinly-veiled personification of a Jesuit. This adds a crucial allegorical dimension to the courtroom scene in which Shakespeare effectively recreates Southwell's trial.

From the vantage point of Catholicism, the very "justice" demanded by Shylock becomes uncannily close to the "justice" meted out by Elizabeth's court to Southwell. Shylock demands that, according to the law, he has a right to cut a pound of flesh nearest to the heart of Antonio. In Southwell's case, the law demanded that Jesuit "traitors" should be hanged, drawn and quartered. The prosecutors not only demanded a pound of their victim's flesh, nearest his heart, but they actually obtained it, physically removing the heart and casting it into the fire.

As Southwell's ghostly presence can be observed throughout The Merchant of Venice, one can read Portia's beautiful "quality of mercy" speech as a plea to Queen Elizabeth to show the Jesuits mercy.

The 'notorious' gatehouse

The most convincing biographical evidence for Shakespeare's Catholicism is one of his final acts in London before retiring home to Stratford: his purchase of the Blackfriars Gatehouse in 1613. The history of this property reveals that it was, as Mutschmann and Wentersdorf described it, "a notorious center of Catholic activities." As its name indicates, the Dominican Order owned it until the dissolution of the monasteries under Henry VIII. It was inherited by Mary Blackwell, a relative of St. Edmund Campion. Other tenants included Mary Bannister, the sister of St. Robert Southwell, and Katherine Carus, the widow of a defiantly recusant judge. According to a contemporary report sent to Lord Burghley, Carus died there "in all her pride and popery."

In 1585, around the time that Shakespeare first arrived in London, Mary Blackwell was accused of recusancy. The following year, a government informer reported his suspicions that the house had become a center for secret Catholic activity: "It has sundry backdoors and bye-ways, and many secret vaults and corners. It has been in time past suspected, and searched for papists, but no good done for want of knowledge of the backdoors and bye-ways of the dark corners."

In 1598, acting on another report that the gatehouse was a hive of recusant activity, the authorities raided the house. Jesuit Father Oswald Tesimond (alias Greenway) stated in his autobiography that he paid a surreptitious visit to the gatehouse on the day after the raid, being informed that priests had remained undiscovered in the house during the search.

The most convincing biographical evidence for Shakespeare's Catholicism is one of his final acts in London before retiring home to Stratford: his purchase of the Blackfriars Gatehouse in 1613.

In 1605, during the Gunpowder Plot to blow up the House of Lords, Jesuit Father John Gerard asked if he could use the gatehouse as a "safe-house" for the plotters to meet in secret. After the plan was discovered, Father Gerard, now the most wanted man in England, appeared in desperation at the gatehouse, disguised with a false beard and hair and stating that he did not know where else to hide. Unlike many of his Jesuit confrères, Father Gerard escaped his pursuers and slipped out of the country in disguise.

Shakespeare leased the Blackfriars Gatehouse to John Robinson, son of a Catholic gentleman of the same name. It was reported in 1599 that John Robinson senior sheltered a priest, Father Richard Dudley. By 1613, the other Robinson son, Edward, entered the English College at Rome to become a priest. It is clear that Shakespeare knew that he was leasing the gatehouse to a recusant Catholic. As Ian Wilson surmised in Shakespeare: The Evidence, Robinson was "not so much Shakespeare's tenant in the gatehouse, as his appointed guardian of one of London's best places of refuge for Catholic priests." Furthermore, John Robinson was not merely a tenant but also a valued friend. He visited Shakespeare in Stratford during the poet's retirement and was seemingly the only one of the Bard's London friends present during his final illness, signing his will as a witness.

Shakespeare died on St. George's Day, April 23, 1616, leaving the bulk of his wealth to his daughter Susanna. Other beneficiaries included several friends who, like Susanna, were known to be recusant Catholics. These legacies support the Anglican clergyman Richard Davies' lament, in the late 1600s, that Shakespeare "dyed a papist." It is equally clear that he lived as a papist, providing Catholics even greater reason to commemorate his life and work.

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Joseph Pearce. "The Catholicism of William Shakespeare." Columbia (December 2016): 21-23.

Joseph Pearce. "The Catholicism of William Shakespeare." Columbia (December 2016): 21-23.

Reprinted with permission of Columbia.

The Author

Joseph Pearce is Director of Book Publishing at the Augustine Institute, editor of the St. Austin Review and series editor of the Ignatius Critical Editions. Among the books he has authored are: Benedict XVI: Defender of the Faith, Literature: What every Catholic should know, Tolkien: Man and Myth, C. S. Lewis and the Catholic Church, Literary Catholics, Race With the Devil: My Journey from Racial Hatred to Rational Love, Beauteous Truth: Faith, Reason, Literature and Culture, Through Shakespeare's Eye, J.R.R. Tolkien's Sanctifying Myth: Understanding Middle-Earth, Unafraid of Virginia Woolf, Solzhenitsyn, and Old Thunder: A Life of Hilaire Belloc.

Joseph Pearce is Director of Book Publishing at the Augustine Institute, editor of the St. Austin Review and series editor of the Ignatius Critical Editions. Among the books he has authored are: Benedict XVI: Defender of the Faith, Literature: What every Catholic should know, Tolkien: Man and Myth, C. S. Lewis and the Catholic Church, Literary Catholics, Race With the Devil: My Journey from Racial Hatred to Rational Love, Beauteous Truth: Faith, Reason, Literature and Culture, Through Shakespeare's Eye, J.R.R. Tolkien's Sanctifying Myth: Understanding Middle-Earth, Unafraid of Virginia Woolf, Solzhenitsyn, and Old Thunder: A Life of Hilaire Belloc.