Solzhenitsyn's cathedrals

- GARY SAUL MORSON

On the literary works of Russian author Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn.

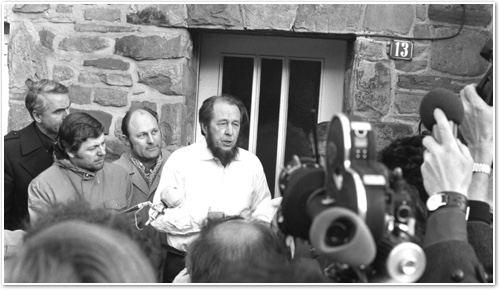

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn talking to reporters in Cologne, West Germany, 1974.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn talking to reporters in Cologne, West Germany, 1974.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons / Dutch National Archives

In Russia, history is too important to leave to the historians. Great novelists must show how people actually lived through events and reveal their moral significance. As Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn explained in his 1970 Nobel Prize lecture, literature transmits "condensed and irrefutable human experience" in a form that "defies distortion and falsehood. Thus literature . . . preserves and protects a nation's soul."

The latest Solzhenitsyn book to appear in English, March 1917, focuses on the great turning point of Russian, indeed world, history: the Russian Revolution.1 Just a century ago, that upheaval and the Bolshevik coup eight months later ushered in something entirely new and uniquely horrible. Totalitarianism, as invented by Lenin and developed by Hitler, Stalin, Mao, Pol Pot, and others, aspired to control every aspect of life, to redesign the earth and to remake the human soul. As a result, the environment suffered unequaled devastation and tens of millions of lives were lost in the Soviet Union alone. Solzhenitsyn, who spent the years 1945 to 1953 as a prisoner in the labor camp system known as the Gulag archipelago, devoted his life to showing just what happened so it could not be forgotten. One death is a tragedy but a million is a statistic, Stalin supposedly remarked, but Solzhenitsyn makes us envision life after ruined life. He aimed to shake the conscience of the world, and he succeeded, at least for a time.

In taking literature so seriously, Solzhenitsyn claimed the mantle of a "Russian writer," which, as all Russians understand, means much more than a writer who happens to be Russian. It is a status less comparable to "American writer" than to "Hebrew prophet." "Hasn't it always been understood," asks one of Solzhenitsyn's characters, "that a major writer in our country . . . is a sort of second government?" In Russia, Boris Pasternak explained, "a book is a squarish chunk of hot, smoking conscience — and nothing else!" Russians sometimes speak as if a nation exists in order to produce great literature: that is how it fulfills its appointed task of supplying its distinctive wisdom to humanity.

Like the church to a believer, Russian literature claims an author's first loyalty. When the writer Vladimir Korolenko, who was half Ukrainian, was asked his nationality, he famously replied: "My homeland is Russian literature." In her 2015 Nobel Prize address, Svetlana Alexievich echoed Korolenko by claiming three homelands: her mother's Ukraine, her father's Belarus, and — "Russia's great culture, without which I cannot imagine myself." By culture she meant, above all, literature.

Solzhenitsyn makes us envision life after ruined life.

Solzhenitsyn was of course aware that, even in Russia, not all writers take literature so seriously and many regard his views as hopelessly unsophisticated. He recalls that in the early twentieth century, the Russian avant-garde called for "the destruction of the Racines, the Murillos, and the Raphaels, 'so that bullets would bounce off museum walls.' " Still worse, "the classics of Russian literature . . . were to be thrown overboard from the ship of modernity.' " With such manifestoes the avant-garde prepared the way for the Revolution, and, when it happened, were at first accepted "as faithful allies" and given "power to administrate over culture" until they, too, were thrown overboard. For Solzhenitsyn, a great writer cannot be frivolous, still less a moral relativist, but must believe in and serve goodness and truth.

Naturally, Solzhenitsyn expressed contempt for postmodernism, especially when it infected Russians. After the Gulag, he asks, how can anyone believe that evil is a mere social construct? Such writers betray their tradition: "Yes, they say, Communist doctrines were a great lie; but then again, absolute truths do not exist anyhow . . . . Nor is it worthwhile to strive for some kind of higher meaning." And so, "in one sweeping gesture of vexation, classical Russian literature — which never disdained reality and sought the truth — is dismissed as worthless . . . . it has once again become fashionable in Russia to ridicule, debunk, and toss overboard the great Russian literature, steeped as it is in love and compassion toward all human beings, and especially toward those who suffer."

Among Solzhenitsyn's many works, two great "cathedrals," as one critic has called them, stand out, one incredibly long, and the other still longer. His masterpiece is surely the first cathedral, his three-volume Gulag Archipelago: An Experiment in Literary Investigation. I suspect that only three post-Revolutionary Russian prose works will survive as world classics: Isaac Babel's Red Cavalry, Mikhail Bulgakov's The Master and Margarita, and Solzhenitsyn's Gulag. For that matter, Gulag may be the most significant literary work produced anywhere in the second half of the twentieth century.

Among Solzhenitsyn's many works, two great "cathedrals," as one critic has called them, stand out, one incredibly long, and the other still longer.

Like Gibbon's Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Gulag is literary without being fictional. Indeed, part of its value lies in its bringing to life the real stories of so many ordinary people. When I first began to read it, I feared that a long list of outrages would rapidly prove boring, but to my surprise I could not put the book down. How does Solzhenitsyn manage to sustain our interest? To begin with, as with Gibbon, readers respond to the author's brilliantly ironic voice, which has a thousand registers. Sometimes it surprises us with a brief comment on a single mendacious word. It seems that prisoners packed as tightly as possible were transported through the city in brightly painted vehicles labeled "Meat." "It would have been more accurate to say 'bones,' " Solzhenitsyn observes.

Every reader recalls the introduction to the chapter on "Interrogation":

If the intellectuals in the plays of Chekhov, who spent all their time guessing what would happen in twenty, thirty, or forty years, had been told that in forty years interrogation by torture would be practiced in Russia; that prisoners would have their skulls squeezed with iron rings; that a human being would be lowered into an acid bath; that they would be trussed up naked to be bitten by ants and bedbugs; that a ramrod heated over a primus stove would be thrust up their anal canal (the "secret brand"); that a man's genitals would be slowly crushed beneath the toe of a jackboot; and that, in the luckiest possible circumstances, prisoners would be tortured by being kept from sleeping for a week, by thirst, and by being beaten to a bloody pulp, not one of Chekhov's plays would have gotten to its end because all the heroes would have gone off to insane asylums.

Comparisons with pre-revolutionary writers provide a constant source of irony. They thought they had seen suffering! Tolstoy and Korolenko "shed tears of indignation" that from 1876 to 1904, the tsars executed 486 people and then, from 1905 to 1908, another 2,200! But from 1917 to 1953, the Soviets on average doubled that total every week. Unlike their tsarist predecessors, prisoners in Soviet labor camps suffered constant hunger, and no other writer has ever described hunger so well. And then, with delicate irony, as if he were an anthropologist describing the customs of a remote tribe, Solzhenitsyn informs us that among prisoners the mention of Gogol, famous for his descriptions of food, was taboo.

Gulag also sustains interest by its core story, the moral progress of the author. Solzhenitsyn's description of how he was arrested leads to his account of countless other arrests, and in this way we learn about every stage of the long process leading either to execution (officially "imprisonment without the right to correspond") or a labor camp. What is particularly impressive is the author's unsparing account of his own moral shortcomings. Arrested as an army officer, he considered himself superior to ordinary people. Over hundreds of pages, we watch his initial naïve assessments of his new surroundings and his slow process of learning the truth about the ideology he once accepted. Gradually he embraces moral truths he had never suspected. Gulag is a real-life Bildungsroman — a novel of how a young person learns about life — with insights about "higher meaning" relevant to us all.

In one memorable scene, Solzhenitsyn describes how a believing Jew shook his worldview. At the time he met him, Solzhenitsyn explains, "I was committed to that world outlook which is incapable of admitting any new fact or evaluating any new opinion before a label has been found for it . . . be it 'the hesitant duplicity of the petty bourgeoisie,' or the 'militant nihilism of the déclassé intelligentsia.'" When someone mentioned a prayer spoken by President Roosevelt, Solzhenitsyn called it "hypocrisy, of course." Gammerov, the Jew, demanded why he did not admit the possibility of a political leader sincerely believing in God. That was all, Solzhenitsyn remarks, but it was so shocking to hear such words from someone born in 1923 that it forced him to think. "I could have replied to him firmly, but prison had already undermined my certainty, and the principle thing was that some kind of clean, pure feeling does live within us, existing apart from all our convictions, and right then it dawned on me that I had not spoken out of conviction but because the idea had been implanted in me from outside." He learns to question what he really believes and, still more important, to appreciate that basic human decency morally surpasses any "convictions."

Once he admits that he has supported evil, he begins to ask where evil comes from. How do interrogators, who know their cases are fabricated and who use torture every time, continue to do their work year after year? He tells the story of one interrogator's wife boasting of his prowess: "Kolya is a very good worker. One of them didn't confess for a long time — and they gave him to Kolya. Kolya talked with him for one night and he confessed."

One way to commit evil is simply "not to think," but willed ignorance of evil already means "the ruin of a human being." Those who tell Solzhenitsyn not to dig up the past belong to the category of "not-thinkers," as do Western leftists who make sure not to know. The Germans, he argues, were luckyto have had the Nuremberg trials because they made not-thinking impossible. This Russian patriot advances a unique complaint: "Why is Germany allowed to punish its evildoers and Russia is not?"

Solzhenitsyn claimed the mantle of a "Russian writer," which, as all Russians understand, means much more than a writer who happens to be Russian. It is a status less comparable to "American writer" than to "Hebrew prophet."

Solzhenitsyn discovers yet another cause of totalitarianism's monstrous evil: "Progressive Doctrine" or "Ideology." In one famous passage, he asks why Shakespeare's villains killed only a few people, while Lenin and Stalin murdered millions. The reason is that Macbeth and Iago "had no ideology." Real people do not resemble the evildoers of mass culture, who delight in cruelty and destruction. No, to do mass evil you have to believe it is good, and it is ideology that supplies this conviction. "Thanks to ideology, the twentieth century was fated to experience evildoing on a scale of millions."

One lesson of Gulag is that we are all capable of evil, just as Solzhenitsyn himself was. The world is not divided into good people like ourselves and evil people who think differently. "If only it were so simple! If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being. And who is willing to destroy a piece of his own heart?"

The core chapter of Gulag, entitled "The Ascent," explains that according to Soviet ideology, absorbed by almost everyone, the only standard of morality is success. If there are no otherworldly truths, then effectiveness in this world is all that counts. That is why the Party is justified in doing anything. For the individual prisoner, this way of thinking entails a willingness to inflict harm on others as a means of survival. Whether to yield to this temptation represents the great moral choice of a prisoner's life: "From this point the roads go to the right and to the left. One of them will rise and the other descend. If you go the right — you lose your life; and if you go to the left — you lose your conscience."

Some people choose conscience. To do so, they must believe, as Solzhenitsyn came to believe, that the world as described by materialism is only part of reality. In addition, there is, as every religion has insisted, a realm of objective values, which are not mere social constructs. You can't make the right choice as a postmodernist.

Once you give up survival at any price, "then imprisonment begins to transform your former character in astonishing ways. To transform it in a direction most unexpected to you." You learn what true friendship is. Sensing your own weakness, you become more forgiving of others and "an understanding mildness" informs your "un-categorical judgments." As you review your life, and face your bad choices, you gain self-knowledge available in no other way. Above all, you learn that what is most valuable is "the development of the soul." In the Gulag I nourished my soul, Solzhenitsyn concludes, and so I say without hesitation: "Bless you, prison, for having been in my life!"

The Gulag was the product of the Revolution, but why was there a Revolution? Solzhenitsyn's second "cathedral," the multi-volume novel The Red Wheel, attempts to answer that question. The title comes from a passage in which Lenin, during his exile in Zurich, sees a train whose engine had "a big red wheel, almost the height of a man." Interpreting the train's relentless power as a symbol of merciless historical inevitability, Lenin thinks:

All the time, without knowing it, you were waiting for this moment, and now the moment had come! The heavy wheel [of history] turns, gathering speed — like the red wheel of the engine — and you must keep up with its mighty rush. He who had never yet stood before the crowd, directing the movement of the masses, how was he to harness them to that wheel?

The Red Wheel consists of four long "knots," or, as Marian Schwartz prefers, "nodes." Like Tolstoy's War and Peace, each volume includes both fictional characters and real historical figures, along with non-fictional essays by the author. Solzhenitsyn also adds countless authentic documents: letters between Nicholas and Alexandra, transcripts of debates in the Duma (the nascent Russian parliament), and a letter from Rasputin to the Tsar warning against war. We read "screens" or instructions for how a scene could be filmed. In the historical sections, the author sometimes switches to small print to indicate strict adherence to fact, with no admixture of imaginative reconstruction. Introducing one sixty-page small-print section, the author suggests that "only the most indefatigably curious readers immerse themselves in these details" while the rest might skip "to the next section in larger print. The author would not permit himself such a crude distortion of the novel form if Russia's whole history, her very memory, had not been so distorted in the past, and her historians silenced." Tolstoy insisted that War and Peace belonged to no recognized genre but was simply "what the author wished to express and was able to express in that form in which he expressed it," and Solzhenitsyn advances much the same claim. Formal experimentation never occurs for its own sake.

The first node, August 1914, focuses on the disastrous Russian military losses in that month, but its real energy lies in its fictional characters. We meet the hero, Colonel Vorotyntsev, a dedicated officer who aspires to modernize the Russian army and, beyond that, Russian society. Such conservative reformers, we learn, represented Russia's only hope to avoid revolution, but by August 1914, there was little they could do. Surrounding the foolish tsar were incompetent time-servers, who viewed the monarchy merely as a source of gifts. Their "marsh-like viscosity" made reform impossible.

But reform had not always been hopeless, and August 1914 includes a hundred-page flashback account of the book's most admirable historical figure, Prime Minister Stolypin, who tried to liberate the peasants from their communes and turn them into wealthy, independent farmers with full legal rights. Unappreciated by the tsar, and insufficiently protected from Russia's countless terrorists, he was assassinated by a double agent in 1911. Lenin himself understood that if Stolypin's reforms succeeded there would be no revolution. This whole section of the book becomes an exercise in counterfactual history. More precisely, the future Stolypin envisioned was Russia's true destiny and the revolutionary path that usurped its place was the counterfactual that somehow became real. "Stolypin's stand could have been and looked like the beginning of a new period in Russian history. . . . 'Another ten or fifteen years,' Stolypin would tell his close collaborators, 'and the revolutionaries won't have a chance,' " a judgment with which the author agrees.

Russia was the first society where, believe it or not, terrorism was an honored, if dangerous, profession — at times even a family business passed on from parent to child.

Russia was the first society where, believe it or not, terrorism was an honored, if dangerous, profession — at times even a family business passed on from parent to child. We trace the history of one such family, the Lenartoviches, whose many members — all but one — pride themselves on their revolutionary "family tradition." The exception, young Veronika, prefers art and symbolist poetry, a dereliction her aunts describe as "nihilism"! To bring her to her senses, they recite "the sacred traditions" of the intelligentsia, focusing especially on women terrorists. "In our day girls used to be blessed . . . with [the terrorist] Vera Figner's portrait, as though it were an icon. And that determined your whole future life." They remind her of Sofya Perovskaia, a governor's daughter who directed the assassination of Tsar Alexander II; of Dora Brilliant, whose "big black eyes shone with the holy joy of terrorism"; of Zhenya Grigorovich, who appreciated "the beauty of terror"; and of Yevlalia Rogozinnikova, who decided to take as many lives as possible by becoming a suicide bomber. "What fanatical zeal for justice!" the aunts proclaim. "To turn yourself into a walking bomb!"

When Veronika questions the morality of such killing, especially random murder, her shocked aunts explain that revolutionaries "are not to be judged by the yardsticks of old- fashioned morality. To a revolutionary, everything that contributes to the triumph of the revolution is moral." All that matters is the terrorist's pure intention: "Let him lie — as long as it is for the sake of truth! Let him kill — but only for the sake of love! The Party takes all the blame upon itself — so that terror is no longer murder, expropriation is no longer robbery. Just as long as the revolutionary does not commit the sin against the Holy Ghost, that is, against his own party." Is it any wonder that the revolutionaries who did take power proved so bloodthirsty?, Solzhenitsyn asks. And why does anyone suppose that revolutionaries, who specialize in violence, will somehow become compassionate when governing?

Veronika later meets Olda Andozerskaia, an unorthodox professor of medieval history who, to the amazement of her students, maintains that historical research must be judged by criteria of truthfulness rather than political usefulness. What's more, "we must accept the conclusions as they come, even if they go against us." Andozerskaia even argues that spiritual values, as well as economic interests, shape history and that "personal responsibility" may demand going against prevailing opinion. If only she were my colleague!

Both August 1914 and the next "node," November 1916, focus on the many liberals who apologized for terrorism. Without their support, the revolutionaries could not have succeeded. Why would privileged, educated people, who would themselves be destroyed should the revolutionaries seize power, offer them cover? This question, as Solzhenitsyn notes, pertains not just to pre-revolutionary Russia, but to many other societies, including those of the contemporary West.

There appears to be a certain "leftward dislocation of the neck obligatory for radicals [liberals] the world over." The Russian liberal Party, the Kadets — Constitutional Democrats — dominated the Duma, and yet, instead of making parliamentary politics productive, they joined with the revolutionaries to make the Duma unworkable. Even when Stolypin endorsed the very reforms they had advocated, the Kadets refused to cooperate, lest they earn the ridicule of those further left. Above all, they always made their first and most important demand unconditional amnesty for all terrorists, including those pledged to resume killing the moment they were released. As Petrunkevich, the patriarch of the Kadets, remarked: "Condemn terror? Never! That would mean the moral ruin of the Party!"

Terror reached an amazing scale. Beginning with the manifesto creating the Duma in 1905, some ten thousand people were killed, twice as many by the terrorists as by the police hunting them. Officials often refused to wear their uniforms because to do so was to make oneself (and one's family) a target. Terror was often random: "Instructions to terrorists recommended that bombs should be made of cast iron, so that there would be more splinters, and packed with nails," while "random shots were fired at train windows." Whole buildings with dozens of innocent bystanders were blown up. Dynamite, "beautiful dynamite," was sacramental.

Educated society greeted these killings "with pious approval, gloating smiles, and gleeful whispers. Don't call it murder! . . . terrorists are people of the highest moral sensitivity." The greater the violence, the greater the glee. Liberals "would sign any sort of petition, whether or not they agreed with it." They continued to demand the abolition of censorship, but prevented any antagonistic publications from appearing. In hospitals, left-wing doctors would treat only revolutionaries: "Any simple soul who makes the sign of the cross is refused admission."

By his own experience, Colonel Vorotyntsev comes to realize that "educated people were more cowardly when confronted by left-wing loudmouths than in face of machine guns." In one remarkable scene, he finds himself in an informal meeting of garrulous Kadets. "Each of them knew in advance what the others would say. But . . . it was imperative for them to meet and hear all over again what they collectively knew. They were all overpoweringly certain they were right, yet they needed these exchanges to reinforce their certainty." Oddly enough, Vorotyntsev, who thinks quite differently, finds himself echoing their beliefs, and wonders: what exactly is the pull that he and other conservatives or moderates experience on such occasions? I have not seen this question, as relevant today as ever, addressed anywhere else, and Solzhenitsyn handles it brilliantly. Vorotyntsev at last breaks free "from the unbearable constraints, the bewitchment." It is his escape from this "bewitchment" that makes Professor Andozerskaia, who witnesses it, fall in love with him.

When the first volumes of The Red Wheel were published, some readers, detecting Solzhenitsyn's Christian belief and disapproving of his portraits of Jews, accused him of anti-Semitism. To be sure, some of his portraits of Jews — most notably, Bogrov, who assassinated Stolypin — are less than flattering. What is more, Bogrov decides to kill Stolypin, rather than the Tsar, because he knows that regicide would provoke pogroms and his first loyalty is to his own people.

Unlike George Eliot's novel Daniel Deronda, in which Jews are invariably portrayed as superhumanly good, here they are no better, but also no worse, than everyone else. Vorotyntsev refutes with disdain the idea, common at the time, of an international Jewish conspiracy. He also calls for equal rights and wonders why Jews are not disloyal to Russia when Russia's enemy, Germany, affords them rights denied in Russia. We know that the wealthy Jewess Susanna Korzner, who argues passionately against persecution of Jews, has her heart in the right place when she declares that "Russian literature is my spiritual home."

One lesson of Gulag is that we are all capable of evil, just as Solzhenitsyn himself was.

At the end of August 1914, a Jewish engineer, Ilya Isakovich, argues with his daughter Sonya and her friend Naum about politics. The whole intelligentsia favors revolution, the young people argue, as if that proves revolution correct. Ilya Isakovich replies that engineers believe in construction, not destruction, and that it takes real intelligence to create wealth, while "poorer heads can attend to distribution." This Jew speaks for the author: "No one with any sense can be in favor of revolution, because it is just a prolonged process of insane destruction. The main thing about any revolution is that it does not renew a country but ruins it." When Sonya asks how a Jew can be a patriot in a society with pogroms, he replies that there is more to Russia than Black Hundreds: "On the one side you have Black Hundreds, and on this side Red Hundreds, and in between . . . a handful of practical people."

Though overtly Christian, The Red Wheel does not treat Judaism, or any other religion, as false. The work's wisest character, Father Severyan — this is a Russian novel, after all! — maintains that a religion proves its godliness by humility, which means not treating other faiths as inferior. He narrates the folktale of seven brothers who look for Mother Truth. Each sees her from a different angle and so all conclude that the others lie and must be slain: "They had all seen the same Truth but had not looked carefully."

The volume that has just appeared in English, March 1917, traces the beginning of the Revolution. To be precise, this volume is only the first of four books comprising March 1917. Like the earlier volumes translated by the late Harry Willetts, Marian Schwartz's rendition is superb. I discovered no errors, and the tone is perfect. (Full disclosure: forty-seven years ago, Willetts was my Oxford tutor, and I collaborated with Marian Schwartz on her recent version of Anna Karenina.)

Unlike August 1914 and November 1916, both of which contain long chapters and longer digressions, the present volume is divided into 170 brief chapters. Almost moment by moment, we follow historical and fictional characters from March 8 to March 11, 1917, as chaos unfolds. Although the Kadets think that history must fulfill a story known in advance, Solzhenitsyn shows us a mass of discrepant incidents that fit no coherent narrative. Later accounts discovering a pattern are simply false, and it is plain that, Hegel, Marx, and all theories of inevitable progress not withstanding, history has no inbuilt direction. It depends on what people do, and people act without benefit of hindsight. Tolstoy, too, argued that novels give a truer portrait than histories because they can show people experiencing events before their outcome was known and when more than one course of events was conceivable.

In scene after scene, no one has the perspective to recognize what exactly is going on. Told that his family is in danger, the Tsar stupidly insists that "this wasn't an insurrection but an exaggeration." Historians have attributed the riots to a bread shortage, but Solzhenitsyn demonstrates that there was no bread shortage, only rumors of one. Everyone in Petrograd expects the regime to use outside troops, as they easily could have. Far from inevitable, the revolution depended on repeated failures to do the obvious.

In the final analysis, The Red Wheel is less a political novel than an anti-political novel. Like so many intellectuals today, who proclaim that "all is political," the revolutionaries reduce everything to political power, but the book's wisest characters know that that is the road to totalitarian disaster. To see life solely in political terms is to misunderstand it. For Solzhenitsyn, the meaning of life lies in the moral development of each individual soul, each person's struggle with the evil within us all, and the achievement of wise humility and compassion for others. We each contain an unfathomable "great mystery." One wise character, Varsonofiev, asks himself: "How long would it take to understand that the life of a community cannot be reduced to politics or wholly encompassed by government? Our age is a mere film on the surface of time."

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Gary Saul Morson. "Solzhenitsyn's cathedrals." The New Criterion vol. 36, No. 3 (October 2017).

Gary Saul Morson. "Solzhenitsyn's cathedrals." The New Criterion vol. 36, No. 3 (October 2017).

Reprinted with permission from The New Criterion and the author, Gary Saul Morson.

The Author

Gary Saul Morson, the Lawrence B. Dumas Professor of the Arts and Humanities at Northwestern University, co-authored, with Morton Schapiro, Cents and Sensibility: What Economics Can Learn From the Humanities. Among his other books are The Words of Others: From Quotations to Culture, Anna Karenina in our time, and The Long and Short of It: From Aphorism to Novel.

Gary Saul Morson, the Lawrence B. Dumas Professor of the Arts and Humanities at Northwestern University, co-authored, with Morton Schapiro, Cents and Sensibility: What Economics Can Learn From the Humanities. Among his other books are The Words of Others: From Quotations to Culture, Anna Karenina in our time, and The Long and Short of It: From Aphorism to Novel.