Newman and His Contemporaries: Introduction

- EDWARD SHORT

The literary critic and biographer Mona Wilson once began an introduction to a selection of Samuel Johnson's prose and poetry with a memorable disclaimer. "I shall say nothing of Johnson's life."

"No one should read even a selection from his writings who is not already familiar with the man. Boswell must come first. This is not to say that he is greater than his writings, or that they are only interesting because he wrote them, but they are the utterances of the whole man: no one else could have written them." This is true of Newman as well. Before reading him, we need to know something of the man himself because his work is the unique expression of a figure of unusual integrity.

"No one should read even a selection from his writings who is not already familiar with the man. Boswell must come first. This is not to say that he is greater than his writings, or that they are only interesting because he wrote them, but they are the utterances of the whole man: no one else could have written them." This is true of Newman as well. Before reading him, we need to know something of the man himself because his work is the unique expression of a figure of unusual integrity.

John Henry Newman was born on 21 February 1801 at 80 Old Broad Street in the City of London. A plaque hangs at the Visitor's Entrance to the London Stock Exchange marking the spot where his birthplace stood. A month and a half after his birth, Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson won the battle of Copenhagen, the hardest fought of all his victories. Later, in 1805, Newman vividly recalled candles burning to celebrate Nelson's victory at Trafalgar. Newman's mother was of French Huguenot stock and his father was a banker in the City. He had two brothers and three sisters. As I show in a forthcoming book, Newman and His Family, it was by addressing his siblings' respective religious difficulties that Newman learned to address those of his contemporaries.

In 1808 he attended Ealing School, where he was greatly influenced by the classical master, Walter Mayers (1790–1828), a moderate Evangelical who introduced him to the works of the great biblical commentator Thomas Scott (1747–1821), the deeply practical character of whose writings Newman would emulate in his own writings. Mayers also impressed on Newman one basal aspect of Christianity, and that was the primacy of dogma.

"When I was fifteen (in the autumn of 1816)," Newman wrote in the Apologia, "a great change of thought took place in me. I fell under the influence of a definite Creed, and received into my intellect impressions of dogma, which, through God's mercy, have never been effaced or obscured. Above and beyond the conversations and sermons of the excellent man, the Rev. Walter Mayers, of Pembroke College, Oxford, who was the human means of this beginning of divine faith in me, was the effect of the books which he put into my hands, all of the school of Calvin."

In 1817, Newman entered Trinity College, where one of his tutors was the legendary Thomas Short (1789–1879), who lectured in Aristotle's Rhetoric. After he passed the age at which Aristotle says that man's powers are at their best, Short amused generations of undergraduates by observing, when he came to the relevant passage, "In those hot climes, you know, people came to their acme much sooner than with us." Despite Newman's poor showing in his final examination, Short was convinced that he could redeem himself and later recommended that he sit for the Oriel fellowship, to which he was duly elected in 1822. In 1825, Newman was ordained a priest. In 1828, he became Vicar of St. Mary's, Oxford where he gave the sermons that would stay with those who heard them for the rest of their lives. The discriminating Scot, J.C. Shairp, later the Oxford Professor of Poetry, who would become a good, if critical friend of Clough, left behind a vivid recollection of the sermons.

Sunday after Sunday, month by month, year by year, they went on, each continuing and deepening the impression the last had made. As the afternoon service at St. Mary's interfered with the dinner-hour of the colleges, most men preferred a warm dinner without Newman's sermon to a cold one with it, so the audience was not crowded—the large church little more than half filled … About the service, the most remarkable thing was the beauty … of Mr. Newman's voice, as he read the Lessons. It seemed to bring new meaning out of the familiar words … Here was no vehemence, no declamation, no show of elaborated argument.

This shunning of all declamatory effect was in keeping with Newman's humility. Although a brilliant man, he was never a pompous man. Nor was he intent on showing how clever he was. Some have suggested that he was egotistical, but the interest he took in himself was free of vainglory. Before converting, he wrote to his beloved Aunt Elizabeth, after visiting his grandmother's house in Fulham where he had spent so many happy days as a child, "Alas my dear Aunt, I am but a sorry bargain, and perhaps if you knew all about me, you would hardly think me now worth claiming." By the same token, he was quick to point out, "Whatever good there is in me, I owe, under grace, to the time I spent in that house, and to you and my dear Grandmother, its inhabitants." If Newman was an egotist, he was a peculiarly self-effacing one, knowing as he did that "where the thought of self obscures the thought of God, prayer and praise languish."

As I show in my final chapter, Newman was intent on preserving as full a record of his life as possible to confute those who might try to misrepresent it. Then, again, the historian in him could not fail to see that there was a useful tale in his own persistent resolve to live the devout life, especially for the English people, who had all but lost the sense of what sanctity means. In this respect, it is amusing to read the testimonials of Oratorians in Newman's Positio, for nearly all of them remark the discomfiture that even the mention of sanctity caused parishioners and Oratorians alike. The interest Newman took in his thoughts and feelings, his fortunes and misfortunes, was not egotistical but documentary. He might have been hesitant to draw parallels between his own life and the lives of the saints but they were unavoidable. In a memorandum regarding his Lives of the English Saints, he shed light on what he saw as the uses of documented sanctity.

"The Lives of the Saints are one of the main and special instruments, to which, under God, we may look for the conversion of our countrymen at this time."

"The saints are the glad and complete specimen of the new creation which our Lord brought into the moral world, and as the 'the heavens declare the glory of God' as Creator, so are the Saints proper and true evidence of the God of Christianity, and tell out into all lands the power and grace of Him who made them." Moreover, Newman saw how documented sanctity could change hearts. "The exhibition of a person, his thoughts, his words, his acts, his trials, his features, his beginnings, his growth, his end, have a charm to every one; and where he is a Saint they have a divine influence and persuasion, a power of exercising and eliciting the latent elements of divine grace in individual readers, as no other reading can have." Indeed, Newman was convinced that "the Lives of the Saints are one of the main and special instruments, to which, under God, we may look for the conversion of our countrymen at this time." That Newman did not consider himself a saint was emblematic of his humility; in one prayer he cries out, "O my God! what am I but a parcel of dead bones, a feeble, tottering, miserable being, compared with Thee!" Nonetheless, the sanctity he documented in his own long life speaks for itself.

Shairp certainly understood why Newman's life merited close study—even by the man who lived it. "The look and bearing of the preacher were as of one who dwelt apart, who, though he knew his age well, did not live in it. From his seclusion of study, and abstinence, and prayer, from habitual dwelling in the unseen, he seemed to come forth that one day of the week to speak to others of the things he had seen and known." This was an important point. One of the reasons why Newman fascinated his contemporaries is precisely because he did not share their worldly preoccupations. Yes, he paid attention to what was happening in England and in Europe: the journalism he wrote for various Tractarian and Catholic papers demonstrates what a well-informed, critical interest he took in political, social and imperial affairs. He was a dutiful and beloved parish priest who never neglected the souls under his charge. He had many friends and was himself a considerate, loyal friend. But he lived outside the world and only entered it to reaffirm the truths of religion. His sermons were the most immediate means with which he accomplished this, and for an introduction to his Anglican sermons, the literary critic Eric Griffiths is one of the best guides.

Newman had an acute suspicion of the workings of imagination in the religious life, of those who 'mix up the Holy Word of God with their own idle imaginings.' … He specifically mistrusts the power of imagination to doll up religious life and deliver it over as a toy for the delectation of a consumer who then 'appreciates' it rather than being judged by it. The sermons persistently warn against religious allure: 'Men admire religion, while they can gaze on it as a picture. They think it lovely in books;' 'Many a man likes to be religious in graceful language;' 'I am much opposed to certain religious novels … they lead men to cultivate the religious affections separate from religious practice;' 'It is beautiful in a picture to wash the disciples' feet; but the sands of the real desert have no lustre in them to compensate for the servile nature of the occupation.' The danger of whetting a taste for religion is that, once aroused, it leads people to consider religion as a matter of taste: they adopt the 'notion that, when they retire from the business of their temporal calling, then they may (in a quiet, unexceptionable way of course) consult their own tastes and likings.' Even the pious delight of his undergraduate audience, their very interest in him, might turn out in a parodic reversal of his hopes and intention to be complicit with that liberalism and doctrinal indifferentism against which he preached.

In 1832, after completing his first book, The Arians of the Fourth Century, Newman toured the Mediterranean with his dear friend Hurrell Froude and his High Church father, Archdeacon Froude, visiting Gibraltar, Malta, the Ionian Islands, Sicily, Naples, and Rome, where he was impressed by the devoutness of the Roman Catholic faithful and the power of the Roman Catholic liturgy, though he continued to regard the Roman Catholic Church as "crafty," "polytheistic," "degrading," and "idolatrous." Whether as an Anglican or a Catholic, Newman never minced his words.

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Edward Short. "Introduction" from Newman and His Contemporaries. T&T Clark International (2011).

Edward Short. "Introduction" from Newman and His Contemporaries. T&T Clark International (2011).

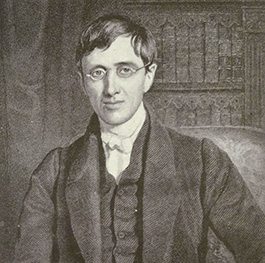

Reprinted with permission from the author. Image credit: William Charles Ross, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The Author

Edward Short is the author of Newman and his Contemporaries, Newman and his Family, Newman and History, and, most recently, The Saint Mary's Book of Christian Verse. He lives in New York with his wife and two young children.

Copyright © 2022 T&T Clark International