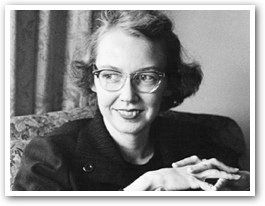

Flannery O'Connor: Stalking Pride

- AMY WELBORN

Flannery O'Connor wrote out of a deep, thoroughly Catholic vision of life, and saw her vocation of writing as essentially telling stories to uncover "mystery through manners, grace through nature."

|

Nine stories about original sin, with my compliments

- Flannery O'Connor to Sally Fitzgerald, December 26, 1954

You could be forgiven if you begin to suspect at some point during your search for Flannery O'Connor's grave that, at an incautious moment, you have somehow slipped right into the middle of a Flannery O'Connor story.

After all, so far in this small town of Milledgeville, Georgia, about 35 miles east of Macon, you have passed a youth prison and a state mental hospital, homes to hundreds of troubled, unusual characters. You are surrounded by the plain fact of the south, from the ghostly, castle-like remains of the first state capital to the sight of an African-American UPS man emerging from the "Strictly Southern Heritage Gallery and Gift Shop," a downtown business packed with Confederate memorabilia, including flags and bikinis made from flags. The store, a sign notes, is closed "Sundays and Southern holidays."

And when you finally reach it — kindly hauled in the caretaker's rundown pickup truck on the suffocating summer day from one end of the cemetery, where you thought she might be, to the other end, where she is — you stand there, next to a stranger. "They still don't want to claim her, do they," he comments wryly, reflecting on the complete lack of any directions to the grave of one of the 20th century's most revered and intensely discussed writers, laid ot rest here 35 years ago last August. You nod in agreement and wonder who placed the broken plastic olive-colored Madonna above the name on the flat marble slab. And if you are finally conscious now of your place in the O'Connor universe, you will know to brace yourself; for any moment, grace may strike — and, no question, it will hurt.

Flannery O'Connor lived but 39 short years. The body of work she left may be small in size, but the stories and two novels are deep in meaning and boundless in importance for the modern reader. O'Connor's talent was recognized during her lifetime, although critics sometimes mischaracterized her work as nothing more than Tobacco Road meets Edgar Allen Poe. Her reputation has only grown since her death, and closer reading — as well as the perspective offered by the wonderful letters collected in The Habit of Being, edited by Sally Fitzgerald — has helped readers understand O'Connor's body of work within the context of her own words:

"I write the way I do because (not though) I am a Catholic. This is a fact, and nothing covers it like the bald statement.

Flannery O'Connor, an only child, was born in Savannah and educated in Catholic schools there. The family moved to her mother's family home of Milledgeville when O'Connor was 12 and after her father died, at the age of 44, of lupus.

O' Connor attended Georgia State College for Women (now Georgia College and State University) and then the Iowa Writer's Workshop, from which she received her master's degree in fine arts in 1947. Her writing was clearly superior — fellow writers at Iowa recall workshop sessions, usually sites of unrepentant critical blood-letting, falling silent after Flannery's stories were read. Her first novel, Wise Blood, was published in 1952.

This darkly comic tale of Hazel Motes, an intense, sharp and uncompromising man running hard from his call to preach the Gospel, was so striking, it prompted Evelyn Waugh to comment, "If this is really the unaided work of a young lady, it is a remarkable product."

Her intentions to lead the writing life up North were cut short when she was diagnosed with lupus herself at the age of 26. She returned to Milledgeville to live with her mother on Andalusia, their farm just north of town. She spent the next 13 years writing, receiving visitors, occasionally venturing forth to give lectures, raising peacocks, painting, and suffering gracefully from the ravages her disease, a pain that rarely, if ever, found its way into the hundreds of witty and profound letters she wrote during those years. She died on August 3, 1964.

So what will you find when you read Flannery O'Connor?

What will probably strike you first is the riot of characters — rural Southerners, incisively drawn with precision and an uncanny comic sense: the self-satisfied "good woman" thanking God He didn't make her either black or white trash, the clueless intellectuals out to lay ignorance bare, traveling salesmen and con artists, preachers, prophets and children filled with ancient wisdom.

But what we have here is no mere Southern Gothic landscape, filled with the grotesque for our entertainment at their expense. O'Connor wrote out of a deep, thoroughly Catholic vision of life, and saw her vocation of writing as essentially telling stories to uncover "mystery through manners, grace through nature."

Her stories, situated in the specific spot of the mid-20th century rural "Christ-haunted" South, dramatize what she accepted as universal truth: that the world has, "for all its horror, been found by God to be worth dying for," and this world broken by sin is fighting that same redemption literally to the death.

"Everybody who has read Wise Blood thinks I'm a hillbilly nihilist, whereas I would like to create the impression.that I'm a hillbilly Thomist," she wrote in a letter in 1955.

O'Connor was deeply conversant in Catholic theology — a glance at her library, on display in the Flannery O'Connor Room at Georgia State College, reveals works by Thomas Aquinas, St. Augustine, Jacque Maritain, Leon Bloy, Ronald Knox, St. John of the Cross, and Baron von Hugel, among others.

She was accused of nihilism because of the violence in her stories. But O'Connor makes clear that her purposes are as far from that as one can get when she wrote in another letter: "The stories are hard, but they are hard because there is nothing harder or less sentimental than Christian realismWhen I see these stories described as horror stories, I am always amused because the reviewer always has hold of the wrong horror."

Her characters are primarily poor and hardscrabble, many bearing physical handicaps as well, but this also serves to point all of us beyond pride to our real condition: "Everybody, as far as I am concerned, is The Poor."

Robert Coles answered the question well when he wrote of O'Connor, "She is stalking pride." For Flannery O'Connor, faith means essentially seeing the world as it is, which means through the Creator's eyes. So lack of faith is a kind of blindness, and what brings on the refusal to embrace God's vision — faith — is nothing but pride.

O'Connor's characters are all afflicted by pride: Intellectual sons and daughters who live to set the world, primarily their ignorant parents, aright; social workers who neglect their own children, self-satisfied unthinking "good people" who rest easily in their own arrogance; the fiercely independent who will not submit their wills to God or anyone else if it kills them. And sometimes, it does.

The pride is so fierce, the blindness so dark, it takes an extreme event to shatter it, and here is the purpose of the violence. The violence that O'Connor's characters experience, either as victims or as participants, shocks them into seeing that they are no better than the rest of the world, that they are poor, that they are in need of redemption, of the purifying purgatorial fire that is the breathtaking vision at the end of the story, "Revelation."

The self-satisfied are attacked, those who fancy themselves as earthly saviors find themselves capable of great evil, intellectuals discover their ideas to be useless human constructs, and those bent on "freedom" find themselves left open to be controlled by evil.

What happens in her stories is often extreme, but O'Connor knew that the modern world's blindness was so deeply engrained and habitual, extreme measures were required to startle us: "I am interested in making up a good case for distortion, as I am coming to believe it is the only way to make people see."

So take a chance, and take a look at Flannery O'Connor. Prepare to laugh, to be shocked, and to think. But most of all, be prepared to see.

![]()

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Welborn, Amy. "Flannery O'Connor: Stalking Pride." Our Sunday Visitor (August 8, 1999).

Published with permission of Amy Welborn.

The Author

Amy Welborn has an MA in Church History from Vanderbilt University. She worked as a teacher in Catholic high schools, and a Parish Director of Religious Education and has been writing full time since 1999. Her articles have been published in venues ranging from Our Sunday Visitor to the New York Times to Commonweal. Amy has written or edited nineteen books including Wish You Were Here: Travels Through Loss and Hope, A Catholic Woman's Book of Days, Friendship with Jesus: Pope Benedict XVI Talks to Children on Their First Holy Communion, The Loyola Kids Book of Saints, The Words We Pray: Discovering the Richness of Traditional Catholic Prayers, Loyola Kids Book of Heroes: Stories of Catholic Heroes and Saints throughout History, Decoding Mary Magdalene: Truth, Legend, and Lies, Prove It! Jesus, Prove It! Church, and Prove It! Prayer. Amy has five children, ranging in age from 29 to 7.

For 8 1/2 happy years beginning in 2000, she was married to Michael Dubruiel, who had worked as an editor for Our Sunday Visitor for nine years, but in the summer of 2008 changed jobs to serve as Director of Evangelization for the Diocese of Birmingham, Alabama. On February 3, 2009, Michael died while running on the treadmill at the gym. Amy's new book, Wish You Were Here: Travels Through Loss and Hope, is a memoir of those first few months, which included a sort of crazy decision to travel to Sicily. Visit her blog, Charlotte Was Both, here.

Copyright © 1999 Our Sunday Visitor