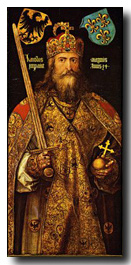

Charlemagne

- EGINHARD

He was very forward in succouring the poor, and in that gratuitous generosity which the Greeks call alms, so much so that he not only made a point of giving in his own country and his own kingdom, but when he discovered that there were Christians living in poverty in Syria, Egypt, and Africa, at Jerusalem, Alexandria, and Carthage, he had compassion on their wants, and used to send money over the seas to them.

|

Charlemagne |

Charles

was temperate in eating, and particularly so in drinking, for he abominated drunkenness

in anybody, much more in himself and those of his household; but he could not

easily abstain from food, and often complained that fasts injured his health.

He very rarely gave entertainments, only on great feast-days, and then to large

numbers of people. His meals ordinarily consisted of four courses, not counting

the roast, which his huntsmen used to bring in on the spit; he was more fond of

this than of any other dish. While at table, he listened to reading or music.

The subjects of the readings were the stories and deeds of olden time: he was

fond, too, of St. Augustine's books, and especially of the one entitled "The City

of God:" He was so moderate in the use of wine and all sorts of drink that he

rarely allowed himself more than three cups in the course of a meal. In summer,

after the midday meal, he would eat some fruit, drain a single cup, put off his

clothes and shoes, just as he did for the night, and rest for two or three hours.

He was in the habit of awaking and rising from bed four or five times during the

night. While he was dressing and putting on his shoes, he not only gave audience

to his friends, but if the Count of the Palace told him of any suit in which his

judgment was necessary, he had the parties brought before him forthwith, took

cognizance of the case, and gave his decision, just as if he were sitting on the

judgment-seat. This was not the only business that he transacted at this time,

but he performed any duty of the day whatever, whether he had to attend to the

matter himself, or to give commands concerning it to his officers.

Charles had the gift of ready and fluent speech, and could express whatever he had to say with the utmost clearness. He was not satisfied with command of his native language merely, but gave attention to the study of foreign ones, and in particular was such a master of Latin that he could speak it as well as his native tongue; but he could understand Greek better than he could speak it. He was so eloquent, indeed, that he might have passed for a teacher of eloquence. He most zealously cultivated the liberal arts, held those who taught them in great esteem, and conferred great honours upon them. He took lessons in grammar of the deacon Peter of Pisa, at that time an aged man. Another deacon, Albin of Britain, surnamed Alcuin, a man of Saxon extraction, who was the greatest scholar of the day, was his teacher in other branches of learning. The King spent much time and labour with him studying rhetoric, dialectics, and especially astronomy; he learned to reckon, and used to investigate the motions of the heavenly bodies most curiously, with an intelligent scrutiny. He also tried to write, and used to keep tablets and blanks in bed under his pillow, that at leisure hours he might accustom his hand to form the letters; however, as he did not begin his efforts in due season, but late in life, they met with ill success.

He cherished with the greatest fervour and devotion the principles of the Christian religion, which had been instilled into him from Infancy. Hence it was that he built the beautiful basilica at Aix-laChapelle, which he adorned with gold and silver and lamps, and with rails and doors of solid brass. He had the columns and marbles for this structure brought from Rome and Ravenna, for he could not find such as were suitable elsewhere. He was a constant worshipper at this church as long as his health permitted, going morning and evening, even after nightfall, besides attending mass; and he took care that all the services there conducted should be administered with the utmost possible propriety, very often warning the sextons not to let any improper or unclean thing be brought into the building, or remain in it. He provided it with a great number of sacred vessels of gold and silver, and with such a quantity of clerical robes that not even the door-keepers, who fill the humblest office in the church, were obliged to wear their everyday clothes when in the exercise of their duties. He was at great pains to improve the church reading and psalmody, for he was well skilled in both, although he neither read in public nor sang, except in a low tone and with others.

He was very forward in succouring the poor, and in that gratuitous generosity which the Greeks call alms, so much so that he not only made a point of giving in his own country and his own kingdom, but when he discovered that there were Christians living in poverty in Syria, Egypt, and Africa, at Jerusalem, Alexandria, and Carthage, he had compassion on their wants, and used to send money over the seas to them. The reason that he zealously strove to make friends with the kings beyond seas was that he might get help and relief to the Christians living under their rule. He cherished the Church of St. Peter the Apostle at Rome above all other old and sacred places, and heaped its treasury with a vast wealth of gold, silver, and precious stones. He sent great and countless gifts to the popes; and throughout his whole reign the wish that he had nearest at heart was to reestablish the ancient authority of the city of Rome under his care and by his influence, and to defend and protect the Church of St. Peter, and to beautify and enrich it out of his own store above all other churches. Although he held it in such veneration, he only repaired to Rome to pay his vows and make his supplications four times during the whole forty-seven years that he reigned.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Eginhard. "Charlemagne" In Vita Caroli Magni. Translated by S.E. Turner.

The Author

Eginhard (Einhard) died in 840. He was a friend of Charlemagne, served as imperial architect, and became abbot of the monastery at Seligenstadt.

Copyright © 1991 Ignatius Press