The Permanent Relevance of Newman

- FATHER LOUIS BOUYER

What struck me at a first reading of Newman's works is how Newman manages to develop in both his personality and teaching an immediate and spontaneous union between fidelity to God and intellectual integrity without these being in conflict.

For Newman, God is never seen as an idea, a notion, but as a concrete reality confronting man in the consciousness of his own human situation in being – the supreme reality, who as such commands of man not only an attitude of absolute respect but the total commitment and surrender of his existence. From the time of what Newman calls his first conversion, when he was still in his teens, this recognition of God appears as neither exclusive of nor opposed to intellectual honesty; rather it is grounded in the basic intuition that the voice of genuine reason and the voice of conscience are not two disparate voices but only two aspects of the single voice of the one true God worthy of the name.

For Newman, God is never seen as an idea, a notion, but as a concrete reality confronting man in the consciousness of his own human situation in being – the supreme reality, who as such commands of man not only an attitude of absolute respect but the total commitment and surrender of his existence. From the time of what Newman calls his first conversion, when he was still in his teens, this recognition of God appears as neither exclusive of nor opposed to intellectual honesty; rather it is grounded in the basic intuition that the voice of genuine reason and the voice of conscience are not two disparate voices but only two aspects of the single voice of the one true God worthy of the name.

This was the immediate, intimate conviction of his youth, following a period of doubt which he clearly perceived as intellectual pride. This same conviction permeates his Oxford University Sermons of his Anglican period, as well as the Grammar of Assent, the masterwork of his whole life, written in the full maturity of his later years. It is the common thread of these two books, evolving to final form in the second. Reason is not to be used in a kind of vacuum, skirting those details of reality bearing a special relation to our fully human development. Otherwise, what takes place is not a genuinely rational process, but an artificial, unhealthy, even cancerous development. It will not lead to a conclusion drawn from reality, but just a variety of pretentious, unreal words, devoid of justification. In producing such elucidations, we have simply forgotten that our mind has been revealed to itself as a moral conscience, as Augustine says: "the witness of someone more intimate to myself than I myself am". As God is unconditionally the master of our thinking as of our acting, rationality and obedience cannot be opposed, being one in their root: that mysterious presence, at the ultimate ground of our personality, which is its divine origin, or, as Saint Thomas says, "Him in whom we live more truly even than he lives in us".

It is only when we realize this as the background or foundation of the whole life of Newman, as of everything that Newman would develop in the most diverse fields of theological speculation, that both the deep organic unity and the equilibrium of his work may be justly appreciated. First of all, this is at the root of his treatment in the 15th and last kof his Oxford University Sermons as in the famous Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine. He has been misinterpreted by the modernists first, and later by interpreters like Jean Guitton, as a champion of the idea that development for its own sake is the chief characteristic of the life of the Catholic Church, while all the distortions of Christianity in the most varied heresies were imagined to be sterile. No greater mistake could be made not only about the real intention of Newman, but about what he himself stated most explicitly. For him, development as a characteristic of every living thing, healthy or unhealthy, leads either to the fulfillment of life or to the decomposition of irreversible death. Calvinism itself, he said, and all the possible Christian "isms", are either stillborn or develop; their development either leads to lasting life or is a deadly decomposition. He disappointed the modernists precisely because he is not interested in development for developments sake, but in how to distinguish a development that leads to death and decomposition from the development that retains the integrity of its germ. Therefore, his attempt will not be to demonstrate how abundantly, how gloriously the Catholic tradition has developed, as compared to spurious or partial traditions of Christianity, but to elaborate a series of "notes" which may enable us to distinguish genuine, faithful developments from the more or less unhealthy ones.

Here again we catch Newman in the same search for integrity which animated his unswerving fidelity to rational consistency as well as to authentic obedience to God, the two complementary aspects of the right use of reason, above all concerning ultimate truth. The integrity of Newmans reflection on aspects of Christian belief and practice (and also in opposition to all forms of integrism and all forms of pretention to exclusive modernity or actuality or futurity), far from opposing genuine ecumenism, brought him to see how and in what manner authentic Catholicism and ecumenism are mutually inclusive, rather than contradictory.

From this perspective his often neglected Lectures on Justification has been acknowledged by such an ecumenist as Archbishop Michael Ramsey as a model for realistic ecumenism.

Protestants have tended in effect to oppose justification by faith alone to a justification including works of salvation, or a justification wrought for us by Christ alone to a justification wrought by our own human merits. However, according to Newman, we ought rather to see justifying faith as involving, not only what Christ has done for us on the Cross, but also his presence in us now as the author of our actual sanctification. Without this sanctification our justification would have no substance. Is this not the ultimate meaning of the affirmation of Saint Paul: "It is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me"?

This corresponds exactly to the conclusion reached a century earlier by one of the greatest and most popular spiritual authors of Protestantism, Johann Ardnt, in his book Wahres Christentum. It is revealing that this same book, published anonymously, would later be translated by Cardinal de Noailles for Catholics as well as by Saint Tikhon of Zadonsk for the Orthodox!

It may be when we consider Newmans work on ecclesiology, however, that we discover at its best how this permanent relevance proceeds from what we have described as his integrity. I am thinking of his lectures on the Prophetical Office of the Church, written while an Anglican, yet reprinted when he was a Cardinal under the title Via Media with no modifications but only some supplementary material and a preface. It is often quoted, but not so often well understood.

In the main body of this work Newman gives us a view of the Catholic tradition which is not only a most inclusive but a most synthetic one. It may be considered at the same time a most illuminating vision of, not only the place of the laity in the Church, but its actual relation to episcopal authority.

For Newman there is a single tradition of the truth of life in the Church, but it presents two aspects which are clearly distinct yet ultimately inseparable. These are what he calls the prophetic and the episcopal traditions, or again, more precisely, two aspects of a single and indivisible tradition.

The truth of the gospel with its vision of faith develops in the whole body of the Church, in the whole Christian people – among the simple faithful as well as the clergy, including the bishops themselves. Now its most intimate development is the development of the truth of life, the development of personal holiness. As to the expression in words of this basic development, it implies, together with personal holiness, intellectual capacities. This latter is a gift no less personal than that of holiness, and could be equally granted to anybody in the Church, clerical or lay, man or woman. This is what Newman calls the prophetic tradition. We must consider the episcopal tradition as inseparable from this, and to some extent indistinct. This latter corresponds to a gift which is not properly that of every Christian, but only of those who have received a share in the supreme pastoral responsibility concerning the whole body of the Church, that is, the bishops acting all in communion under the leadership of the Bishop of Rome. What distinguishes the specifically episcopal form of the tradition is an ultimate capacity, when controversy arises, for judging expressions of the faith to be authentic or inauthentic, determining which are to be received as faithful or rejected as lacking in authenticity or clarity. Only those who have received as a collective, indivisible responsibility the charge of shepherding the flock of Christ are endowed with this capacity as an essential part of this charge committed to them by Christ himself. "He who hears you hears me, he who rejects you rejects me."

In itself, as is emphasized by Newman, this does not necessarily mean that only a bishop will be able to find the needed doctrinal formula. In the very first Ecumenical Council of the Christian Church, which had to define the reality of the divinity of Christ, it was Athanasius of Alexandria who suggested the word finally canonized: Homoousios (of the same nature) as the Father; at that time Athanasius was only a deacon.

We may add that even a simple priest such as Thomas Aquinas may be acknowledged and proclaimed by the supreme authority in the Church as a Doctor, that is, a teacher having authority. And not only laymen, but lay women as well have been given this same title – Saint Catherine of Siena and Saint Teresa of Avila.

These views provide us with a firm basis for a proper recognition of the relation between the laity and what we have come to call the hierarchy, meaning the different ordained ministries or just the episcopal ministry. It is significant to note, however, that Pseudo-Dionysius, who introduced the term, meant not the ministers but the influx of grace, through them but from Christ alone, which establishes all the Church in a communion of grace. In the same way, the epistle of Clement of Rome (probably the most ancient Christian text after the New Testament) comparing Christian worship with that of the Jews, did not hesitate to say that in the Church of the New Testament there is no longer a merely passive laity, but that lay people themselves correspond now to what were the ordinary priests of the old covenant. This is typical of that patristic Christianity which Newman did so much to restore to our knowledge and imitation. Also the bishop in the New Testament (or the "presbyters" who are now associated with his presidential function) fulfills, as representative of the Head (Christ), in the midst of his whole body, the function formerly reserved to the high priest alone.

It is in the same spirit that Newman today sees the whole body of the Church, laity included, cooperating in its active development of the truth of life. This development once again is realized through the holiness of individuals with the gift of a capacity for expressing their own experience, notwithstanding the fact that only those responsible for the common life of the whole body will possess the gift to judge, that is, to distinguish with authority between the expression of truth which is genuine and that which is not. Nonetheless, this special episcopal gift itself would have no object if it were not for the constant contribution of all the members to the life, and to the intelligence of that life, of Christ in us.

Closely connected with this comprehensive view of the situation of life and light in the Church, Newman as a cardinal insists on the triple aspect of that life of the light of truth in the Church in his Via Media (a point later emphasized and much developed by Friedrich von Hugely. Newman distinguishes between the three offices of the Church: the doctrinal, the cultic and devotional, and the regal. From his exposition it becomes clear that mankind being what it is, still fallen even in the process of recovering holiness, will not expect a simultaneous development of these three aspects, however inseparable they are, without more or less serious conflicts or at least tensions between them. The doctrinal development at times may obscure that of holiness. In addition, the latter may degenerate if needed doctrinal developments are lacking. And both, at times, may appear to hinder a peaceful exercise of authority, which itself, in turn, may be tempted to be inattentive or too easily afraid of the other factors.

Here again, Newman has too often been misunderstood by apologists only too anxious to make use of his calm and patient analyses. Newman does not mean in the least that a lack of coherence between these three items, at times unavoidable owing to human weakness, is not to be deplored. On the contrary, for any attentive reader, it is clear that for Newman this means no reform of the Church will ever be made once and for all. The Church always has to be both "semper reformata" and "semper reformanda", even as she remains the one true Church, indubitably willed by Christ, but willed as ever prone to see her weaknesses and ready to correct them.

Another aspect of the problem of the laity and its role in the Church is treated in the Idea of a University and the related essays. Here again Newman undertakes to clarify the relation between culture – especially intellectual culture, but more generally "humanism" as widely understood today – and properly religious culture tending directly to the development of the spiritual life itself. It is amusing to see how many superficial readers have completely misunderstood his description of the gentleman as the aim of the formation expected of universities. For Newman, however, it is clear that the gentleman, as the free and liberal citizen, is meant to be a first sketch of what a full Christian should become. (It is only as an unconscious caricature that it degenerates from within, while taking care to keep the appearances.) Humanist culture, perfected by Christianity, although having its first roots in Greco-Roman civilization, is a necessity for the Christian in the world. It is there he develops his human activities, always illuminated from above and rectified by the light of the gospel. Conversely, there will never be an effective influence of the gospel on man at large and human society if a properly Christian formation for clerics and laity persists in ignoring the common culture of the day, in both its good points and its possible defects.

More importantly, we are in danger of trivializing our Christianity, both when we disdain and ignore culture at large and when we submit to it passively, uncritically. The Christian not only must know what it means to be "a man of the world" and eventually be capable of acting as such; but he must also take care not to reduce his Christianity to the level of the more refined authentic humanism of his day or a fortiori, to allow the development of his properly Christian culture to fall below the level of his humanistic culture. Together with these basic problems, and as a component part of them, Newman has treated in a way no less lasting in its relevance the more special question of the relation between the formation of man as such and his specialized professional formation. And regarding a more specific aspect of this problem, Newman has some extraordinarily interesting views on the relation of science both with technology on the one hand and with human formation at large, whether directly religious or not.:

Here I would emphasize the importance of a much neglected passage of the Idea of a University, in which he comes unexpectedly near to observations made quite recently by philosophers such as Wittgenstein (in the Brown and the Blue books of his last period), and also Karl Jaspers. I mean first that, like Wittgenstein, he underlines the fact that there are different views of the world which simply correspond to different practical approaches to its reality. According to the different angles of vision implied, they may appear to be contradictory at first sight, while in truth they are simply complementary. Still it is not possible to combine them into a pseudo-synthesis, which would afford only an incongruous hodge-podge. But, as Jaspers has shown in his turn, some may be more "englobing" than others, without being substituted for them. And this appears to be the case, eminently, for an authentic religious view of the world, compared to either a scientific or merely philosophical approach. No less does this intuition (so typically Newmanian, albeit none of his readers until now seems to have grasped it) correspond to what is suggested by the best specialists of the comparative history of religions, having rejected as pure fantasy all attempted reductions of the religious phenomenon to anything else. (One could compare, for example, what Mircea Eliade says in his book The Quest.)

My impression is that we Christians at the end of the twentieth century are still very far from having grasped the importance of such considerations or, even more, from having drawn all the implications of such views for our present cultural situation.

The modern apologists of Christianity are apparently not much more aware of the exact significance of Newmans considerations in his Grammar of Assent which treat not just probability in understanding the assent of faith (in the line of Joseph Butlers argumentation in his famous Analogy), but also treat what he himself calls the convergence of independent probabilities. With his discussion, we have a fully modern and most illuminating explanation (as well as an exposition in terms of modern psychology) of the very Thomistic view of faith as being both supernatural and, owing to that supernatural character itself, without any implicit contradiction, at the same time free and rational.

But, however important all that we have tried to summarize may be, the most lasting element in Newmans approach to the Christian faith, in a world which he was one of the very first to describe as post-Christian, lies elsewhere. Bremond, in his strange book entitled (in the English translation) The Mystery of Newman, has a whole chapter, pleasant to read, on Newman as a poet. His own conclusion is clearly that all this is only the final evidence of a lack of sound rationality in Newman. This is the typical view of an incurable sceptic, combining an unbelieving reason with a lack of spiritual experience, but taking refuge in an attempted confusion between mysticism and poetry. Here as elsewhere, Bremond simply lends his own unsolved contradictions to the object of his brilliant but finally highly subjective studies.

Newman, undoubtedly, is almost unique in the way he uses poetry, not so much in his own verses, which are usually rather indifferent in poetic quality, as in his ordinary approach to religion. But by poetry we must understand here, as has been so well shown, especially by Coulson, something not very far from what Coleridge, following Schelling, calls "imagination" (meaning truly creative or rather re-creative imagination rather than the mere "fantasy" of any waking dream). Here there would be too much to say. Let us once more observe only that Newman simply makes more concrete for us another formula of Saint Thomas. This formula, completely forgotten (if not implicitly rejected) by too many of our modern "Thomists", is that the best evidence for the truth of Christianity is just what he calls its "sublimity".

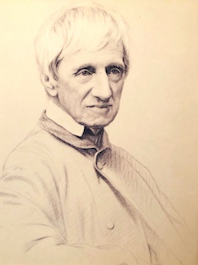

![]()

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Father Louis Bouyer. The Permanent Relevance of Newman. In Newman Today. Papers Presented at a Conference Sponsored by the Wethersfield Institute New York City, October 14-15, 1988, (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, (1989): 165-174.

Reprinted by permission of The Wethersfield Institute.

The Author

Father Louis Bouyer (1913-2004) was a member of the French Oratory and one of the most respected and versatile Catholic scholars and theologians of the twentieth century. A friend of Hans Urs von Balthasar, Joseph Ratzinger, and J.R.R. Tolkien, and a co-founder of the international review Communio, Bouyer was a former Lutheran minister who entered the Catholic Church in 1939. He became a leading figure in the Catholic biblical and liturgical movements of the twentieth century, was an influence on the Second Vatican Council, and became well known for his excellent books on the history of Christian spirituality. Among his many books are: Christian Initiation, Newman, His Life and Spirituality, The Spirit and Forms of Protestantism, The Word, Church, and Sacraments in Protestantism and Catholicism, The Invisible Father, Christian Mystery, and Women Mystics.

Father Louis Bouyer (1913-2004) was a member of the French Oratory and one of the most respected and versatile Catholic scholars and theologians of the twentieth century. A friend of Hans Urs von Balthasar, Joseph Ratzinger, and J.R.R. Tolkien, and a co-founder of the international review Communio, Bouyer was a former Lutheran minister who entered the Catholic Church in 1939. He became a leading figure in the Catholic biblical and liturgical movements of the twentieth century, was an influence on the Second Vatican Council, and became well known for his excellent books on the history of Christian spirituality. Among his many books are: Christian Initiation, Newman, His Life and Spirituality, The Spirit and Forms of Protestantism, The Word, Church, and Sacraments in Protestantism and Catholicism, The Invisible Father, Christian Mystery, and Women Mystics.