Under the Radar

- BEN WATTENBERG

New. Newer. Newest. Shocking, More Shocking, Most Shocking. Shocking-est. Abstract. Super-abstract. If you went by the headlines, you'd think that this is all there is to contemporary art. But it's not. We'll show you another side of today's art scene in our Think Tank Special, "Art Under the Radar".

|

Ben

Wattenberg |

BEN WATTENBERG: Hello, I'm Ben Wattenberg, moderator of Think Tank.

The art that

made the headlines in recent decades did so mostly because of its ability to provoke.

But some very talented artists are not all that interested in what's new, shocking,

obscene or political, super-abstract or provocative. They're interested in art

Period. And they don't think what they're doing is old hat or stale

In

fact, many will tell you the avant-garde is what has become stale.

When

the cutting-edge of contemporary art is put on the auction block, you will often

find it at Christie's. And it ain't cheap.

Phillipe Segalot was Christie's

international director of contemporary art.

SEGALOT:

This is a work by an Italian artist called Maurizo Cattelan. It's

called La Nona Ora in Italian, The Ninth Hour, in English. And we chose

it because we thought it was an extraordinary work of art.

The artist

tried to depict uh, the Pope, John Paul the second, struck down by a meteorite.

That probably came from the ceiling and actually broke the ceiling. And that's

why we have broken glass on the floor. Actually, it's not only a sculpture; it's

a room-size installation, the red carpet, the glass is part of the work.

This work, Woman in Tub, was executed in 1988 by the Amercan artist Jeff

Koons.

There are actually two figures in this work. One that you can

see, who is a naked woman in a bath tub, and one that you cannot see, who is supposedly

a man underneath, you know, in the water. And you see him through the snorkel,

which is apparent here in the work. And knowing Jeff Koons, you know, I'm sure

he would like to have been the man, you know, underneath.

The work you

can see here, Henry Moore Bound to Fail, was executed in 1967 by the highly

important artist American artist Bruce Nauman. and it's actually

a cast of his own back, uh, it was done in wax over plaster. And it represents

the situation of the artist, you know, towards creation.

I believe Bruce

Nauman is one of the most important artists in the century, he was certainly very

influential.

And this work is actually

very timeless. It's also a very, very strong concept. And a very moving wok,

when you look at it.

BEN WATTENBERG:

Including commission, that's 9.9 million dollars. If you believe in market theory,

it's a fair price. After all, that's what people are willing to pay for contemporary

art.

Hilton Kramer was the chief art critic at the New York Times

for seventeen years.

What's the problem with contemporary art today?

HILTON KRAMER: The problem with contemporary

art today is a profound lack of belief in what we used to, without embarrassment,

call 'the higher values of life,' whether they religiously defined or socially

defined, morally defined. With that lacking in the art, then you're left with

a kind of free-floating hostility toward life itself and that's what defines a

lot of this contemporary art.

JED PERL: We're

in a time where there is tremendous activit and energy and freshness among artists,

but a lot of it is not getting to the public that might want to see the work.

And that's because there is a very powerful art establishment that has fossilized

ideas, fossilized values. And in that sense, we are in a time that in many respects

is not unlike the late 19th century.

BEN WATTENBERG:

At the close of the nineteenth century, France was the center of the

art world. There, public taste was dictated by official art schools known collectively

as the Academy, which accepted only certain kinds of paintings for its exhibitions.

Nymphs and virgins were very much in vogue. Soon artists began to rebel â?¦

JED PERL: There were artists who were using

old ideas of color, of structure, of storytelling, but were trying to give them

new kinds of energy, new kinds of force, a new dynamic. And that art, I think

scared many people. It made many peopleuneasy.

JED

PERL: So you begin to have what is seen as the model of what advanced

avant-garde art is. It's an art that pushes ahead of where the audience at large

is, and then there's a kind of tension, argument between the audience and the

artist.

BEN WATTENBERG: In the early

part of the twentieth century, the avant-garde took off. Artists like Vasily Kandinsky

were creating the first truly non-representational paintings. Marcel Duchamp submitted

a urinal for an art exhibition. Then he drew a mustache on the Mona Lisa! Ooh,

how shocking!

BEN WATTENBERG: The

experiments and "isms" continued. When World War II began in the 1930's, many

European artists fled to America, and the center of the art world shifted from

Paris to New York. This set the stage for the first truly American modern art

movement: Abstract Expressionism.

HILTON KRAMER:

By my reckoning, the last bona fide avant-garde movement wereâ?¦.were the American

Abstract Expressionists in the forties and fifties because abstract expressionism

was the last big modernist movement to meet with resistance over a significant

period of time by the principle cultural institutions the press, universities,

the museums, the critics and so on.

BEN WATTENBERG:

But by the late 1950s, much of that had changed. Abstract Expressionism had become

the darling of the art world. It was mainstream not only in New York's

hothouse art world, but all over America.

Looking back, not everyone

was impressed.

David Levy is the director of the Corcoran Gallery of

Art in Washington, DC.

DAVID LEVY:

The Abstract Expressionists were being driven by the sense that they had to move

fast, and the couldn't wait for the normal evolution art-making. They stopped

looking at the world. They were looking inside their heads, or whatever, and they

were making action painting and all of this stuff which is really quite

self-indulgent in many respects.

In your judgement, was this a wrong turn?

DAVID LEVY: I do think it's a wrong turn.

BEN WATTENBERG: The evolution of art continued

to accelerate. The focus of art shifted toward ideas and away from images.

HILTON KRAMER: What happened in the sixties

was a complete breakdown in the institutions of what they could any longer define

as art. You no longer had to create a work of art, you could nominate something

to be a work of art.

LYNNE MUNSON: When

standards are jettisoned, and anything becomes art, then it's jut a matter of

how well can you sell the thing that you have created.

BEN

WATTENBERG: Lynne Munson is the author of Exhibitionism: Art in

an Era of Intolerance.

LYNNE MUNSON: If

you want to have a career in art, and you want to show at the best galleries,

and you want to win grants and awards and be included in the most important museum

shows, and have a successful career, making shock art is the safest thing that

you could do today.

LYNNE MUNSON: Today's

establishment class of artists the shock artists what they do is

instead of pleasing the public, what they do is kind of find clever ways to criticize

the public, or really attack the public in some ways, in an effort to please art

elites.

BEN WATTENBERG: When financial

analysts tout a stock, it tends to rise.When art critics focus on art that is

new-newer-newest, that's the kind of art that tends to go up in value at

least for a while.

Christie's Auctioneer: "All

done at six hundred thousand. Passed at six hundred thousand."

If art

can reflect markets, it can also mirror physics: every action has a reaction.

From the beginning there was resistance to the cult of the new and the shocking.

Edward Hopper, for example, was among the top-selling artists in the 1950s, even

as Abstract Expressionism was making the headlines. And today, too, many fine

American artists are working under the radar.

BEN

WATTENBERG: Even in New York City, the capital of the cutting-edge,

something else has been flourishing.

The Center for Figurative Painting

was founded by Henry Justin in 1999.

HENRY JUSTIN:

I don't like to use he word overlooked, but I thought with my sense

of the way art has been packaged over the last 10, 20, 30 years, I thought the

idea of great painting in itself and the focus on it was sorely of lacking.

BEN WATTENBERG: The centerpiece of Justin's

collection is the work of Paul Georges.

MR. JUSTIN:

He's taken in a sense the space and color and form of Abstract Expressionism,

one of the isms, and applied it to traditional genres of still life, of

landscape, and of figurative painting.

PAUL

GEORGES: That center that opened is a total accident. His name is Henry

Justin, and we call him "just in time." He just got here in time for me not to

die poor. (laughs)

BEN WATTENBERG:

Today, at age 78, Paul Georges is still painting almost every day. His New York

studio is filled wth canvases covering a lifetime of work.

PAUL

GEORGES: Suddenly people are somewhat interested in me. If you spend

30 years in the wilderness then you get the slightest little glimmer. It's very

nice.

BEN WATTENBERG: Paul Georges

was born in Portland, Oregon and moved to New York City in the early 1950s. He

had studied art in Europe and, before that, in America with the famous Abstract

Expressionist, Hans Hofmann. But he didn't exactly follow in his teacher's footsteps.

GEORGES: â?¦ If you come back from France to

a pristine America with three filling stations on four corners, the fourth corner

does not need a filling station. And that's what I felt. Abstract Expressionism

had used the territory. It didn't make it bad, just was no place for me in it.

BEN WATTENBERG: Throughot the 1950s and '60s,

Georges began to develop a truly unique representational style of painting.

GEORGES: In the Renaissance, they invented

perspective, and it goes to a point, or points on the horizon. If I stand like

this, my feet point to the horizon. Every representational thing I do sticks.

Unless I can make it fly. And that's here I'm safe. Because here it flies.

GEORGES: In Hans Hofmann's school

I learned that things shouldn't close like that, because that's perspective

they should open like that, because that's freedom. So, things that open are free.

Viola.

BEN WATTENBERG: Turns out,

Georges has a thing with freedom. Throughout his career he has considered himself

free to paint whatever he wanted and bristles when asked to explain his

work. For Georges, explanation threatens inspiraton.

GEORGES:

If someone asks me why, I often say "because."

GEORGES: I don't know what inspiration is, but if you say, "why did

you do it," you right away make it impossible to do it. And that's why I made

the picture "The Mugging of the Muse."

GEORGES:

I'm a traditional painter but that doesn't mean I'm a bore. If you understand

tradition, like I think I do, it is a magnificent thing.

GEORGES:

In a certain way the Renaissance painters had the guts of their time.

They made a tradition and they were the people who were important in their time.

Modern art is what's important now. I'm a modern artist. It doesn't mean that

I do what all the modern artists do. That isn't modern art. Art isn't one thing.

MS. ISH: Making a beautiful painting is a

fearful topic at this time. People are afraid of not seeming serious. So there

are things that you shouldn't paint, and sometimes it's extremely tempting to

do them.

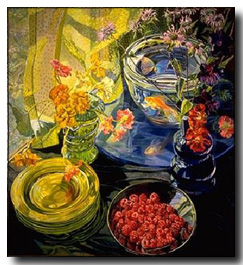

BEN WATTENBERG: Janet Fish's

studio in Vermont holds her two latest still life paintings with flowers,

glass and lots of color.

BEN WATTENBERG:

As a young artist fresh out of graduate school at Yale, Fish knew all about the

abstract and conceptual art of the moment. But she decided instead to paint the

world as she saw it.

|

Raspberries

by Janet Fish |

MS. FISH: I

mad my choices not because I disliked what other people were doing. I felt a

lot of it was really interesting. It wasn't good for me and it didn't seem honest

to me. I wanted to work with the world that I was in.

BEN

WATTENBERG: Fish has been showing at the DC Moore Gallery in New York

City.

BRIDGET MOORE: The fun thing

about representing Janet is that the paintings almost sell themselves. She's produced

work in a particular sensibility that's uniquely hers. It's actually often copied

by other people. There's a vibrancy that she brings to it the absolute

excitement of color and light in pictures.

Janet

Fish: "C'mon, Maisy. Look! Look a ball!"

Dog barks.

MS.

FISH: There is a kind of light in Vermont that's very different than

in the city, where the sot in a sense mutes the colors.

MS.

FISH: I think I've been painting so long, I don't really analyze it

as I'm working. Sometimes it's the color and shape, and sometimes it's the kinds

of echoes of meaning, or whatever, the things have and it just depends

on the painting. Now, in this case of the one I'm working on right now it's really

just more about my life here, I guess. Being in Vermont and watching the dogs

play. There's something about the scene.

MS.

FISH: It's hard sometimes to explain what you're doing because it is

so nonverbal, and you do hope that your paintings will say it for you.

BRIDGET MOORE: Janet's work is very life-affirming,

it just brings a lot to the viewer it gives them energy. It gives them an optimistic

perspective.

BEN WATTENBERG: For

some people, Fish's paintings can be a little too optimistic.

MS.

FISH: I found when I threw babies into the painting, I thought here's

a pretty good forbidden subject matter. I mean, if you want to be taken seriously.

If it's a dead baby it's fine, but It's sort of on a par with sunsets.

That's another thing you're not supposed to paint.

GRAHAM

NICKSON: What's happening today is not really very much different to

what was happening in the past, in the 18th century, in the 19th century, even

in the 16th century. Where in fact, you know, you have a dominant mainstream,

and then a few odd peripheries of people working away and doing extraordinary

things, that are not necessarily part of the mainstream, but in the end, end up

being the ones that survive.

BEN WATTENBERG:

Graham Nickson's caree outside the mainstream began in 1972. He had just arrived

in Rome for an artists' fellowship when he discovered that someone had broken

into his car. Everything he'd done so far as an artist his whole portfolio

was stolen.

GRAHAM NICKSON:

â?¦ Suddenly I'm in the middle of Rome and I'm about to take on a new studio and

a two-year fellowship and I actually have no history. It's been wiped out.

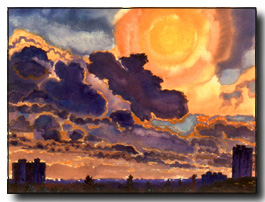

|

Florida

Series II, No. 16 By Graham Nickson |

NICKSON:

So I'm on the top of the roof of the studio complex and I'm looking

at this sky and there's this incredible sea of vermilion and ultramarine and azure.

And I suddenly realized thatthis is an extraordinary event. But I realize that

the most dangerous thing to do at that time would be to paint a sunrise or a sunset,

because it was so cliché and so hokey that I couldn't possibly do it. But, of

course, you know, being foolhardy, I made a sort of rather miserable attempt,

and I tried the next following night. And before I knew it, I was actually painting

the dawns. And after two years I had painted every dawn and sunset available;

I mean, every one. Maybe I missed about twelve. But that would turn out to be

one of the seminal experiences in my life.

BEN

WATTENBERG: Nickson is the Dean of the New York Studio School, which

has been a holdout for traditional standards of training.

Nickson: "You have to say, 'What is important? What is crucial about

the information that I'm looking at?"

GRAHAM

NICKSON: It's unfortunately the fact that in a lot of places, all over

the world, drawing has been phased out. You know, it's like Latin, it's become

a kind of dead language. Well, the truth is that it's not a dead language, it's

very vital and it's very alive. And in fact probably one of the most radical,

one of the most truly avant-garde acts of the moment is trying to make sense of

one's sensations and trying to paint a metaphor for that experience.

BEN WATTENBERG: That's exactly what the New

York Studio School's founders believed when they opened the school in 1964. It

was a time when art was becoming just another liberal arts subject in universities

around the country.

Nickson: Let

your eye and you hand your charcoal be synonymous with each other.

Let the charcoal almost be your eye as you travel, finding those pathways through

the space.

BEN WATTENBERG: At the

New York Studio School, students work with practicing artists and they

learn about nothing other than drawing, painting, sculpture and art history.

BEN WATTENBERG: Since Nickson's arrival, each

semester at the Studio School begins with a two-week long Drawing Marathon.

BEN WATTENBERG: Their drawings may look rough

right now, but these students are learning the basics of the visual language.

During these two weeks, Nickson says his students draw as much as they would in

an entire semester as most art schools.

NATE

HESTER: It's a demanding thing. It's hard on your body, standing in

one place for that long. And then when you're working on something that's 4x5,

it's a lot of up and down. It's like the Stairmaster all day. And I think mostly

it's jst, it's mentally challenging. You're pushing yourself to see the world

in ways that you hadn't seen it before.

NATE

HESTER: I don't really feel like I've made a successful drawing, but

I feel like I may have the tools now that I might make one before I die.

GRAHAM NICKSON: I think something new is afoot

I think the belief that there's a new possibility in working from observation

has come back to a lot of young people.

GRAHAM

NICKSON: Drawing the figure today is as relevant as it was to the ancients,

because in a way it's still as mysterious. Rembrandt's brilliance hasn't unlocked

all the mysteries.

BEN WATTENBERG:

Speaking of Rembrandt â?¦ Can a serious artist today paint in the fashion of the

old masters? The work we just saw at the New York Studio Shool is traditional,

but it's obviously rooted in the 20th century. Is it possible, though, to go back

even before that hundreds of years back to find centuries-old technique

to the art of today? There are those who are trying.

BEN

WATTENBERG: Jacob Collins opened the Water Street Atelier in the mid-1990's.

This converted warehouse space now serves as an intense training ground for about

two dozen artists.

JACOB COLLINS: There

are people here practically all the time. Everybody comes, they have the key,

They're working from the model, they're working from the casts; after a while

people start to paint still lifes and landscapes. Particularly the still lifes

are great for people to support themselves. It's also a great way to start to

really to organize, you know, compositions.

BEN

WATTENBERG: Collins and hi students, along other painters around the

country, are taking an even more radical step away from the art establishment.

And they're doing it by making paintings that look . . . old-fashioned

in fact too old-fashioned, even for some on the traditional side of the art world.

Still the work sells.

DEBBORAH SPAINIERMAN:

Part of the reason that Jacob's work and the work of his atelier group

are so successful is because there is a huge demand for works that are beautiful.

These are paintings that feed the soul. There may be a higher purpose,

there may be a higher meaning, there might even be rhetoric behind it but at the

very most basic place they're beautiful and they're meant to be beautiful.

|

Tracks

in the Snow by Jacob Collins |

COLLINS:

People do really like drawing and painting that comes out of a 19th

century non-modernist tradition. People do respond to it. People really like it.

I mean, I like it. I've always loved it.

COLLINS:

I feel like my interest, for almost my whole life as an artist, has

been to try to go back to when, there was a sort of a draftsmanship that I could

connect to. And as I became more and more passionate in that pursuit, I became

less and less interested in modernism.

COLLINS:

I'm beginning a new self-portrait. I'm working on the drawing in charcoal,

trying to get the gesture and the personality, just to generally hew out the shape

and spirit of the figure. I don't know whether I'm capturing myself when I paint

a self-portrait. It's hard to interpre yourself. Maybe I'm just expressing some

search or some kind of fantasy about how I might wish I were.

COLLINS:

When I think about the paintings that I love, like those Rembrandts

and, you know those Titians, one of the things that I love is the balance in these

artists of reason and emotion. That's one of the things I love and that's what

I guess I'm pursuing some idea that you can be trying to solve problems

with logic and think hard and at the same time expressing some mysterious side

of yourself or of the world around you, or capturing in a portrait or a figure,

capturing a sort of a mystical quality to the way people are.

COLLINS:

There's almost like an alchemy there that you're making something here

that is at the same time representing something there.

COLLINS:

Of course they're old-fashioned, but I gues I'm trying to make them

really beautiful. And I don't think anybody would mistake one of my paintings

for a painting that was done any other time. I mean, I'm trying my hardest to

do something well and to do it with creativity and passion, and sometimes, if

people are very passionate, they'll end up doing something new.

BEN

WATTENBERG: As you might imagine, all of this activity spawned a movement

within a movement.

Stefania de Kenessey is a classical composer. Like

Jacob Collins, she has chosen tradition over the avant-garde.

DE

KENESSEY: As a child I grew up knowing so-called avant-garde or so-called

20th century music as much as I did 18th, 19th or 16th century musics. So for

me the idea of having dissonant music at my fingertips was nothing new. I always

loved beautiful music more than I loved dissonant, harsh stuff.

BEN nWATTENBERG: In fact, she wrote the music you've been hearing throughout

this program.

DE KENESSEY: There are

very few composers like myself who are really trying to do something that's quite

new and quite traditionally grounded at the same time. And I thought it would

be really interesting to connect up with painters who were in a similar situation,

and poets and architects. And as it turns out, there's a whole younger generation

of people working in all those areas who are very much of a similar bent as myself.

BEN WATTENBERG: De Kenessey has just restored

an old apartment as a music studio and as a meeting place for like-minded

artists, a group that calls itself the Derriere Guard.

Frederick Turner

is a poet, a philosopher and a professor at the University of Texas. Richard Sammons

and his wife Anne Fairfax are architects. Their architecture firm reovated and

decorated this studio. And Jacob Collins, who met de Kenessey just recently, has

supplied the paintings that now hang on the walls.

BEN

WATTENBERG: Congratulations on your new headquarters. Who would like

to explain to me the derivation of the phrase, the Derriere Guard?

MS.

DE KENESSEY: Well, since I coined it, perhaps, I should bear that burden.

Uh I was looking for some term that would somehow convey to the general

public that there's a new, a new avant-garde out there, which is different from

the real avant-garde, which has become the establishment.

BEN

WATTENBERG: De Kenessey staged the first public Derriere Guard Festival

in 1997. The event featured a keynote speech by novelist and provocateur, Tom

Wolfe. Though many of the art world at large and even some of those in the traditional

camp ignored the Derrier Guard, the event sold out all four days.

MS.

FAIRFAX: The exciting thing about the Derriere Guard is this interdisciplinary,

you know, cross-section that we get that we listen to Steffi's music and it resonates

with us and we look at Jacob's paintings and we just go "wow." This is

we feel like we're at home.

MR. WATTENBERG:

So you're all in the same room, in the same clubhouse, in the same movement. What's

the commonality?

MR. TURNER: We all

love beauty.

MR. SAMMONS: The good,

the true and the beautiful.

MR. TURNER:

You know, just as when modernism first emerged or when romanticism emerged or

the Renaissance emerged, there was a historical process, and a social process,

a cultural process, in which people weregetting together, were thinking together,

were involving the lively and interesting people in their cultures and that's

sort of more or less what we want to do now.

MR.

TURNER: I love the great modernists. But there is a time when to create

the future. The present must break the shackles of the past, but there is also

a time when to create the future, the past must break the shackles of the present.

And I felt shackled by the present.

BEN WATTENBERG:

Music with a melody, poetry that rhymes, paintings and sculpture that look like

something, architecture with grace the Derriere Guard says these forms

are timeless.

DE KENESSEY: One of

the problems, of course, of contemporary society is that all the arts are taught

in complete isolation from one another. So to find out that there's a common spirit

amongst all these arts is vey, very liberating, and an enormous source of strength

and inspiration for all of us because we understand that there's something going

on. There's a historic shift in this way.

JAMES

F. COOPER: There is a major movement going on and I think it will prevail.

BEN WATTENBERG: James Cooper is editor

of American Arts Quarterly, a magazine published by the Newington Cropsey

Foundation in Hastings, New York.

JAMES F. COOPER:

The mission of the Newington Cropsey Foundation is to preserve works of Jasper

Cropsey and other members of the Hudson River school and draw a connection between

contemporary artists, painters, sculptors and the values, the timeless values,

that one recognizes in Hudson River School art and in other major art movements

of the past.

JAMES F. COOPER: This

is ur major gallery for showing contemporary art.

There are many highly

qualified figurative artists doing very original, creative work.

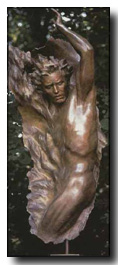

This

is a beautiful bronze angel, sculpted by Frederick Hart We regard him as a pivotal

artist in changing the direction of contemporary art. When I first met Frederick

Hart, I said, I'm really delighted to meet you, because if I hadn't found you,

I would have had to invent you.

|

Innocence

by Frederick Hart |

BEN

WATTENBERG: In 1989, a Washington Post Op-Ed piece got James

Cooper's attention. It was written by Frederick Hart. "Once," it said, "art served

society rather than biting at its heels. Once, under a banner of beauty and order,

art was a rich and eaningful embellishment of life, embracing not desecrating

its ideals." Cooper decided he had to meet Hart.

JAMES

F. COOPER: I'm having lunch with Rick and he said, have you ever seen

my sculpture at Washington National Cathedral? I said, I've never heard of it.

And there's no fault of mine, because there had been no articles written about

it. We went there on a Friday afternoon. There were workmen still working on the

façade. And I recall that they started to descend, climbed down the scaffolding

as we were approaching. It was almost like a movie. And I recall being amazed.

JAMES F. COOPER: There is a moment

in the history of art where a work of art is created that has the power, the beauty

to change things. And art movements come out of that; whole paradigm shifts come

out of that. That's why Manet is important, that's why Picasso is important, and

ne day, increasingly, Frederick Hart will be important.

Frederick Hart

is one reason we're doing this program. In 1999, just before his death, I did

a one-on-one interview with Hart for Think Tank. The program drew more

viewer mail than any other had until that time and about 99 percent of it favorable.

Viewers loved his work and they agreed with what he had to say.

BEN

WATTENBERG: There's this wonderful book about you called, Frederick

Hart: Sculptor. And in it Tom Wolfe writes about, "the most ludicrous collapse

of taste in the history of the American art world." And I guess he's talking about

modern art generally, and he points to you as an exemplar of someone who is trying

to move against that trend, and maybe you could give me a little fill-in on that.

FREDERICK HART: When I was in art school in

the 60's, action painting and pop art were realy coming into the fore. And what

you think of today as contemporary art was really just becoming enshrined and

enthroned in the American cultural hierarchy. The world of art that I had suddenly

found myself in, in 1961, was just not what I had dreamed of living. So I rebelled

completely against the whole modern establishment, or the modern academy, if you

will, and just went off completely on my own, seeking, you know, a completely

traditional or classically-oriented artistic endeavor.

BEN

WATTENBERG: Frederick Hart learned his trade the old fashioned way:

as a stone carver for the National Cathedral. While on the job, he heard about

a competition to design a new work of sculpture for the West Front of the Cathedral,

modeled on the creation theme. Three years later, in 1974 Hart was chosen for

the job. He was 31 years old.

BEN WATTENBERG:

Wolfe uses a word here a number of times aboutyour work, and he calls it heroic.

FREDERICK HART: Mm hmm.

BEN

WATTENBERG: What does what does that mean?

FREDERICK

HART: Well, I think it's because the orientation is, in my work, and

in much of the work that, you know, that I have admired throughout history, essentially

leans toward what you would call the heroic possibilities of mankind. It's oriented

towards celebrating and embodying what I would call the nobility of the human

spirit.

FREDERICK HART: I am not purely

looking for aesthetic beauty, but it's part of the whole. There's something about

the pursuit of beauty that has profound moral implications, in my view, and it

has to do with essentially what I would call religious instinct or spiritual instinct.

FREDERICK HRT: I think really that

it was that same kind of motivation that carried a lot of the best early modernists

works into being. When Monet painted Water Lilies, and when Van Gogh painted

the stars in that famous painting Starry Night, I think they both had profound

religious experiences in the creation of those works. That's the kind of thing

I'm trying to get at and what I think is valuable in art.

BEN

WATTENBERG: Around the time Hart completed his creation sculptures,

he entered another major sculpture competition for the Vietnam Veteran's

memorial. His design placed third out of more than 1400 entries. But the winning

design, Maya Lin's polished black granite wall, stirred controversy.

Nat Sot: Vietnam Veteran: "This is not a memorial

to mourn or grieve. This is a memorial to honor those who served."

B>BEN

WATTENBERG: After extended debate, a compromise was reached. Frederick

Hart would create a figurative sculpture to complement the Wall the Three

Soldiers.

BEN WATTENBERG: Is the

picture of those three soldiers heroic, to use our earlier word?

FREDERICK

HART: What I very often say is that it's really a heroic statue disguised

as a realistic statue. Because the substance, the emotional substance of what

I tried to do there or wanted to do was to reveal some of the true nobility of

spirit of the Vietnam veteran, what they endured, the kind of anguish they went

through both on the battlefield and at homecoming.

BEN

WATTENBERG: What do you guess those three guys are thinking when they

look at the Wall?

FREDERICK HART:

Well, I like the best version of hat, that I've heard, is one Marine said

he felt they were looking for their own names (laughter) which I

think is very good because that's sort of what combat's all about, you know, out

there looking, you know, seeing if your name is coming up.

BEN

WATTENBERG: One year after Rick Hart's death, a thousand people attended

a memorial service at the Washington National Cathedral.

|

Ex

Nihilo figure No. 4 by Frederick Hart |

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Ben Wattenberg (host). "Think Tank: Under the Radar." Think Tank 2002.

This article reprinted with permission from Think Tank.

Think Tank is made possible by generous support from the Smith Richardson Foundation, the Bernard and Irene Schwartz Foundation the Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation, the John M. Olin Foundation, the Donner Canadian Foundation, the Dodge Jones Foundation, and Pfizer, Inc.

Think Tank with Ben Wattenberg is a half-hour weekly discussion show focusing on deeper trends, conditions, and ideas behind the week's headlines. Each week, host Ben Wattenberg is joined by panelists uniquely qualified to discuss topics such as public policy, politics, arts and entertainment, culture, science and technology, and medicine. Think Tank has been broadcast nationally on PBS each week since 1994.

THE HOST

Ben J. Wattenberg is a Senior Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, D.C. He is the moderator of the weekly PBS television program Think Tank with Ben Wattenberg. Wattenberg's current project is a book tentatively entitled The New Demography: How Dpopulation Will Shape the Future. The book deals with dramatically falling fertility rates in both the rich and poor nations, and speculates on the geo-political, economic, commercial and cultural implications.