The Decline and Renewal of Christian Art

- MICHAEL D. O'BRIEN

Why the disappearance of the Christian artist in seemingly benevolent states? Surely this phenomenon points to the deadening of spritual faculties in any materialist society, including our own.

|

Michael

O'Brien |

The

several artists I know who are also refugees from the former Communist regimes

of Eastern Europe have each expressed dismay over the condition of their new home.

In Moscow we were suffering, one painter said. We were dying and starving, but we loved each other, we artists. We looked at each other's work and we understood it.

I hate your country, said another. There, they kill us, but here they kill the heart. You are already dead. You are a dead people!

This, from a former professor at the Moscow Art Institute, a man hounded by the KGB, with half of his friends dead or missing. A violent complex emotion was released in these harsh words, a reaction that we ignore at our own risk. He gave voice to what is felt by most expatriate artists in my acquaintance: they feel that the people of the West have by and large become unable to understand what is being said to them. We listen without hearing, look without seeing. It is not that the immigrant artist produces imagery too esoteric for comprehension or limited by a provincial experience. On the contrary, his suffering has allowed him to break through to perception of universal truths, the perennial object and language of art. The modern North American simply has no time, inclination, or apparatus to read correctly the face of reality.

The pain of this is especially acute for those Christian artists who had survived in Soviet states by making clandestine religious imagery, some of them willing to live as non persons at great sacrifice in order to pursue their art. They cannot understand why there is so little interest in their work in the West, despite the fact that it is usually technically and spiritually superior to that produced by our own small number of religious artists. The dearth of Christian artists in the West is an additional puzzle, for it would appear that many avenues of development lie open to gifted persons of faith. No imprisonment, death, or even destitution await them here.

But the West is no longer Christian and is sliding rapidly into various forms of paganism. The refugee can well understand a pagan state functioning according to its convictions, but it is a cause of surprise and bitterness for him to find a local church culture that in many places has become sterile and invaded with the utilitarian spirit. A great majority of our churches are full of opulent decoration in poor taste, and outfitted with cheap factory art, devoid of a sense of real art, presence, or reverence. To speak out against this degradation of the House of God merely strikes the Western ear as pride or as a violation of the democratic spirit. To the European eye, however, it is clear that some great crime, some colossal but unmentionable tragedy, has occurred in North American church culture

Only in propaganda art is an image considered slave to ideology, a truth not lost on those who have endured ersatz culture. It is a surprise, then, for the newcomer to find in North American churches the employment of art not so much as incarnation of the truth, which is its proper role even in the most catechetical liturgical art, but as a decorative advertisement for the truth a subtle but important difference.

In Painting and Reality (1957), Etienne Gilson laments that churches have largely become so many temples dedicated to the exhibition of industrialized ugliness and to the veneration of painted non-being. Gilson asserts that an authentic religious image has a being of its own which does not merely reflect what is already created but adds a new dimension, a unique enlargement of our understanding of the image of God. Degenerate religious art may have a rudimentary existence, but it is not authentic. It propagates falsehood and thereby removes man from an awareness of what truly exists. In her book on aesthetics, Feeling and Form (1953), Susanne Langer confirms Gilson's analysis of most contemporary church art, and adds that such works corrupt the religious consciousness that is developed in their image, and even while they illustrate the teachings of the Church, they degrade those teachings . . . Bad music, bad statues and pictures are irreligious, because everything corrupt is irreligious. She further states, Indifference to art is the most serious sign of decay in any institution; nothing bespeaks its old age more eloquently than that art, under its patronage, becomes literal and self-imitating.

The Restoration of Culture

In fact, the Church is not indifferent to the arts and in a multitude of ways has expressed her concern for the renewal of culture in society and a rediscovery of the sacred in religious culture. In 1974, the Vatican Collection of Modern Religious Art opened with a dazzling display of 600 works of twentieth century religious art, a collection which continues to expand. Pope Paul VI inaugurated the exhibit with an address to an international group of artists, reassuring them that, It is not true that only a determined criteria of the art of the past has free and exclusive entrance here. It is not true that the dominant criteria of contemporary art are madness, passion, purely cerebral and arbitrary abstraction. Paul VI recognised that however much highly creative persons might be estranged from the Church, they had not become alienated from the sacred, for there still exists in this arid secularised world . . . though sometimes marred by obscene and blasphemous profanations, a prodigious capacity for expressing, besides the human, the religious, the divine. If for more than a century the Christian community has not been producing a genuinely religious art it is largely because such insights so rarely penetrate to all levels of the Church. Occasionally there emerges a gifted artist who is also a believer, and such individuals may be led to serve the cause of Church art, but they must navigate a minefield of adversity.

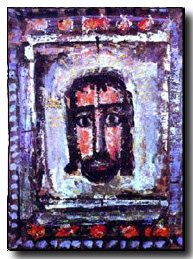

But the presence of a William Kurelek or a Georges Rouault is not sufficient evidence that a renewal of sacred art is in fact underway. By far the majority of creative people in our time have turned away from organized religion, and even disavow any connection with the sacred. Yet the sacred persists, submerged in the subconscious. Without knowing it, many artists are at work revealing the holy simply by virtue of their sincere probing of the created world. Their art is not made as a theological statement, but it bears witness to that reality which theology attempts to penetrate. Theology and art, each in its way, are gropings toward a comprehension of light, and beyond it to the source, the Uncreated Light. The artist of integrity is as concerned with truth and falsehood as is the theologian, for he senses that his life somehow hangs in the balance. He has no other source than his perceptions, and if he is not faithful to these his art will die. It is a humbling fact that many Christian artists, with more spiritual and intellectual resources at their disposal, no longer know how to create an art that is true. They may see far enough to read the deposit of faith but fail to integrate it with artistic vision. In their search for a proper reading of creation they might learn much from those whose faith is weak but whose commitment to truth as it is revealed in creation is uncompromised. Secular artists of this kind are few in number. They may not see as far, but what they do see they see well.

|

Face

of Christ Georges Rouault |

Nevertheless,

even the modern artist of integrity is a victim, deformed by the anti-incarnational

movements of certain streams in Western thought. He suffers precisely at the point

of rupture between faith and creativity, between faith and reason, between truth

and love, which is so endemic to our era. This radical disconnectedness is not

merely an intellectual position, an aesthetic philosophy, but is a fundamental

break within his own being.

If the highly creative person of our times struggles valiantly against these handicaps, we must not lose sight of the fact that he is indeed a severely disabled creature. Like the Christian artist he senses some ultimate mystery hidden within the startling reality of his creative powers. Yet he cannot give it its true name. Thus, he searches desperately for philosophical systems that give meaning to his pain and to his inarticulate longings. For example, the effect of Wassily Kandinsky's Concerning the Spiritual in Art, first published in 1911, can scarcely be overestimated. More than any other work it was to influence the thinking of the world's artists by opening up the possibilities in abstract art. For Kandinsky, colour and rhythm were themselves the meaning. Meaning was not to be found in what they said about some other being. The idea was intoxicating because it provided the philosophical basis for painters to break through into unexplored territory.

Generations of artists have since followed, and the expanding constellation of abstract schools is evidence of how much scope is possible. It ranges from a visceral automatism, which attempts to express subconscious forces freed from moral or aesthetic restraints, passes through abstract expressionism, to a purely cerebral abstraction devoid of emotional content, and culminates in anti-art, the demolition of artistic media as the ultimate act of Art. It is not surprising that such schools can sometimes be in violent opposition to each other by no means the internecine wars of a hermetically sealed art world. Such conflicts are the surface eruptions of profound spiritual problems in modern man. The common theme, beneath the differing styles and ideological feuds, is an immanentised or flattened cosmos. The transcendent God is dead. Perhaps man, too, is dead? Burdened with the colossal weight of this question and the silence of God which greets it, the culture of negation has arisen.

At first many artists abandoned traditional realism in order to revert to primitive art forms, attempting to plunge through the stultifying layers of a decaying civilisation into a supposed natural innocence, a primaeval purity of vision. Needless to say, the gates to Eden remained resolutely shut, and in despair painters increasingly turned away from natural creation into an interior universe. The modern movement took as many forms as there were personalities who could articulate their pain. Manifestations ranged from the poignant, the silly, and the cynical to eruptions of the diabolical. A multitude of schools of abstraction developed cryptic languages from which one may decode variations on the theme: no one listens, no one hears, words have become pointless in a meaningless universe. The artist has become the paradigm of the lonely hero wandering in an absurd and hostile environment. He becomes the mythic quester for whom there is no holy grail. Reality begins and ends in his ego. Cut loose from a hierarchical cosmos, he must now stagger around this existential landscape, searching for his own lost face.

Paul Klee (1879-1940), himself an abstract impressionist, wrote in his Diaries that The more horrible this world is, the more abstract art will be, while a happier world brings forth a more realistic art. Klee recognised that abstraction represented a retreat from reality, as if from an assault too painful to witness or to bear. In a world deprived of faith, the redemptive value of the Cross could only appear as an absurdity. Klee and a host of gifted creators were among the first victims of the cold winds which nineteenth century philosophy were blowing over the flesh of man.

After World War II the unprecedented crimes of civilised man were disclosed, increasing the general atmosphere of despair. Sartre, Camus, and other existentialists offered a philosophy of heroic despair, a form of modern stoicism which for a time provided the motivation to create. Moreover, Hitler and Stalin had tried to suppress the avant-garde and to harness realism to the cause of propaganda. The avant-garde mistook this as proof that their movements were instruments of liberation. They did not see that when violent revolution collapses in tyranny it will tolerate no kind of revolution other than its own.

To arrive where we started

The anti-materialism of abstraction is clearly concerned with the spiritual, but so too was the ancient heresy of Manichaeism; its dualistic vision of matter and spirit bears some resemblance to the theories of abstraction. There is a similar attempt to liberate spirit from matter through an asceticism which at times approaches hatred of the flesh. In no sense, then, can pure abstraction be called a Christian vision, though it may point in directions that are helpful to Christian art. The Christian vision of creation holds that all things are to be restored in Christ. Matter is to be transfigured, not escaped or annihilated. Even Kandinsky implied that the greatest works may lie not in the direction of absolute abstraction but back along the line toward the cognitive image that has been freed of materialism.

We

shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

will

be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

- T.S. Eliot,

Four Quartets

There is a revival of figurative imagery in art today, an arriving where we started, but with altered eyes. The contemporary religious artists is learning that if total abstraction is not the natural habitat of the sacred, neither is its opposite, photographic realism. A tenth-century Chinese painter, Ching Hao, expressed it well: Likeness can be obtained without spirit; but when truth is reached, spirit and substance are both fully expressed. He who tries to express spirit through ornamental beauty will make dead things.

There is a sense of deadness in much modern realism, a failure often overshadowed by its stunning technical achievement. Merely to reproduce the visible field is not an act of creation, however exact it may be. It is largely an extension of the eye, in much the same manner as the camera. The power of real art is that it selects and eliminates in order to focus. Even photography may become an art when the photographer achieves precisely this level of economy. The truth of the image rises or falls with how clearly the artist focuses on what is essential. He distils the mystery of experience without explaining it scientifically; nor does he need to extract moralisms to shake in front of the viewer's eyes in order to communicate the moral order of the universe. Vision cannot be detached from moral sense, for the artist must paint from an awareness of grace as it appears in nature. He may or may not call it grace or recognize its source, but if he is aware of it then his work will be effective.

In the work of numerous contemporary artists there is a process of gazing into nature and human experience, a consciousness of reality which is speculative and contemplative. Northrop Frye names this faculty the language of awareness, which can be developed into a level of mind normally called the imaginative. It moves beyond a literal vision of life, yet avoids the opposite pole of fantasy. It produces what is called in literary criticism the anagoge, an interpretation of a word, passage, text, or (in this case) a visual image that finds beyond the literal, allegorical, and moral sense a fourth and ultimately spiritual or mystical sense, that is rooted in natural law.

Thus, an artist may paint an image of a poor man, for instance, not as social commentary or to arouse sentiments of any kind, but as an act of revelation. Through the vulnerability and limitations of his subject the artist enlarges our grasp of the existential poverty of the human condition. The subject matter is ourselves. The viewer is not asked to analyse his state. He does not rest in a surface account of reality, nor in a sociological, psychological, or formalistic critique of the work. He is led into wider rings of mystery. What the anagoge is about is no less than illumination. This sheds light on the false conflict between being and doing. In focusing on being, the anagoge leads the viewer to a state of union with the subject matter. In the example of the poor man this would effect a deep and lasting identification with the poor. An emotional or even journalistic rendering of poverty, on the other hand, might stimulate an outburst of pity but the viewer's perspective remains essentially detached, and his response would tend to be short-lived. He remains an observer, a consumer of imagery.

Through imagery that springs from authentic sources in the interior life, (including religious symbolism, dreams, icons, anagoges and a host of other forms) man develops languages with which to communicate the inexpressible. He is touched and healed as what lies buried and unresolved within is brought to light. The truth, literally, sets him free. In Horse and Train (1954), a classic work by the Canadian realist Alexander Colville, a horse gallops headlong down a railroad track toward an onrushing train. The feeling of dread elicited has deeper sources than one's feelings for horses or trains. It is an image of the human condition in the twentieth century. The beauty of the unbridled horse, free in its natural power, is about to be confronted by the unnatural force of a machine. Will all that is creative, intuitive, and mystical be obliterated by the destructive aspects of blind mechanisms? Will systemic solutions to the problem of man demolish the ultimate meaning of the human person? Will the omni-competent State prevail over the truly human community? Will the bomb have the final word, or will the poem? The artist does not tell us. His task here is to present a revelation of polarities. In an age of fragmentation and false dichotomies he imparts an urgent message without telling it. It is a cry of protest rising from the spiritual intuitions of a people, mediated through the voice of its artist. This faculty is of high value in any healthy society. But in overtly suppressive regimes there are no protests which fail to produce the disappearance of the protester. This begs the question: why the disappearance of the Christian artist in seemingly benevolent states? Surely this phenomena points to the deadening of spiritual faculties in any materialist society, including our own. It is a warning. It tells us that we are being violated.

As the cultural revolution reaches its final phases, the rendering down of the miraculousness of being proceeds apace. It deforms entire nations of people, who no longer can bear negativity because they have at some fundamental, unacknowledged level, ceased to hope. Only the eyes of Christian hope can gaze unflinchingly into the darkness of our times. The artist of hope creates images of man restored to the imago Dei, the image and likeness of God within us. By the same token, he protests when we settle for a tragic mimicry of that image (one thinks especially of Goya or Dante in this regard). No such protests would be possible if the artist did not believe that something better is still possible for us. In most creative people, the artistic impulse is a passion to integrate what is disintegrated, to seek out harmonies lost to the consciousness of the larger populace which lives in multiplicity and separateness while experiencing inarticulate longings for unity. If by religious we understand the word in its root sense of religare, to bind together, then all authentic art is religious. Thus, a work of art which is properly bound together bears an irresistible attraction, even when it is presenting unpleasant truths. There is a mysterious integrity radiating from it. Truth-love, matter-spirit, sacred-mundane, are not expressed as dualities. They are, as in Horse and Train, an illumination variously called insight, vision, or wisdom about a deeper order. It is a word reflecting back, and drawing us back, to the larger integrity of the Word, that power of truth and love which impels all of existence, a power which is living and active, sharper than any two-edged sword, piercing to the division of soul and spirit, of joints and marrow, and discerning the thoughts and intentions of the heart (Hebrews 4:12).

The Christian artist

If images of truth are to assist in the liberation and healing of man, the artist will inevitably confront forces which work to defeat the coming of God's kingdom. He will not survive this combat if he fails to become a person of prayer. He will be often tempted, and those temptations which ruin large numbers of vocations to sacred art are rarely blatant. On one hand he may find so little response and spiritual direction within the regional churches that discouragement will overwhelm him. Many gifted Catholic artists turn to the secular art world for this reason, resolving their dilemma by practising a private Christianity and a public noncommittal art. If they achieve the integrity of a Colville they have achieved much; yet something has been lost to the Church. Alternatively, an artist may be tempted to produce works readily acceptable to parochial committees with undeveloped artistic sense. He would do well to recall that committees produce little art, but a people must have an abundance of inspired signs and symbols as a necessary cohesive of their identity. A people, however, does not produce such fruit spontaneously, out of nothing, as it were. If the spirit of his people is waning or compromised with the world, the artist will find little to sustain him on the human level. He will be condemned to a solitary exploration which is full of peril.

The artist is called to a sacred ministry within the Church. To misunderstand the sanctity of his calling is not difficult. He may be satisfied with a religiously successful image and conclude that he has fulfilled his function. In The Science of the Cross, Blessed Edith Stein wrote about Saint John of the Cross as an artist and as a disciple of the crucified Christ. Many a Church artist, she points out, has portrayed the crucified Christ, but this is not what makes him a sacred artist. The crucified Christ asks that He be equally free to create something, but of the material of the artist's own life: the artist himself, along with every other believer, is to be formed into the image of the one who carried the Cross and died on it.

There is no bypassing this. The Cross is written into all existence; so too is the Resurrection. The artist who wishes to speak of these two central Christian mysteries must enter fully into them. He must be willing to accept poverty. He must accept to be taken where he would rather not go. Whether he speaks through anagoge or icon, he must die and be reborn.

The Catholic vision would call the triad of perception faith, reason and imagination Wisdom. When all three elements are present an art is born that nourishes the soul. Transcendence and immanence meet; hope replaces naive optimism and pessimism. The goodness of being is affirmed even in the depth of suffering. Man begins to find his bearings and to know his own true face.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

O'Brien, Michael. "The Decline and Renewal of Christian Art." Second Spring (August/September 1994): 29-35.

Published with permission of Second Spring.

The Author

Michael D. O'Brien is an author and painter. His books include The Father's Tale, Father Elijah: an apocalypse, A Cry of Stone, Sophia House, Theophilos, Island of the World, Winter Tales, Voyage to Alpha Centauri, A Landscape with Dragons: the Battle For Your Child's Mind, Harry Potter and the Paganization of Culture, and William Kurelek: Painter and Prophet. His paintings hang in churches, monasteries, universities, community collections and private collections around the world. Michael O'Brien is on the Advisory Board of the Catholic Education Resource Center. Visit his web site at: studiobrien.com.

Michael D. O'Brien is an author and painter. His books include The Father's Tale, Father Elijah: an apocalypse, A Cry of Stone, Sophia House, Theophilos, Island of the World, Winter Tales, Voyage to Alpha Centauri, A Landscape with Dragons: the Battle For Your Child's Mind, Harry Potter and the Paganization of Culture, and William Kurelek: Painter and Prophet. His paintings hang in churches, monasteries, universities, community collections and private collections around the world. Michael O'Brien is on the Advisory Board of the Catholic Education Resource Center. Visit his web site at: studiobrien.com.