Saint Jerome in His Study

- DENIS R. MCNAMARA

During a lifespan that crossed from the 4th to early 5th century, Saint Jerome was a priest, a monk, a pope's secretary, a desert hermit, and head of a monastery in Bethlehem.

But the Church remembers him in the canon of saints as a scholar and translator of the Bible who exemplified a holiness of life worthy of emulation. Widely known as one of the greatest of the Latin Fathers, Jerome commented on the Scriptures, weighed in on theological controversies, wrote hundreds of letters and homilies, and completed the herculean task of translating the Bible into Latin from both Greek and Hebrew. Known for his sharp tongue, intolerance of laxity, contemplations on death, and intellectual acumen, Jerome's dedication to scholarship and profound love of Scripture affect the Christian's experience of prayer to this day.

Jerome in his study

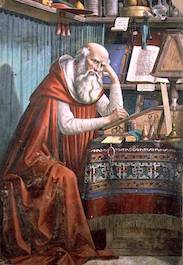

Though many artists have shown Jerome as the emaciated ascetic kneeling on rocks while living in a cave, Domenico Ghirlandaio painted him in a well-furnished study on the walls of the Florentine Church of Ognissanti in 1480. The initial stirrings of the Renaissance and its love of all things ancient had matured by the late 15th century, and Jerome held more than a pious interest to Renaissance thinkers. A contemporary of Saint Augustine of Hippo, Jerome fascinated Florentines for having acquired Christian knowledge and holiness in the early centuries of the Church while its feet were still dipped in classical learning. Accordingly, he is shown as a scholarly Doctor of the Church, as indicated by his dress in cardinalatial red with his cardinal's hat on the shelf behind, even though in actuality this attire developed several centuries later.

Jerome's small study shows a wealth of detail worthy of a scholar and translator: pens, ink, scissors, books, parchments, eyeglasses (also not yet invented in his time), and candles. Though Jerome shows a contemplative stillness, his active life is indicated as well: he holds a pen in his hand, translating Scripture into the Latin edition now known as the Vulgate. The two inkwells subtly indicate this work: both the black ink, for text, and red ink, for rubrics, have splashed against the wood of his writing desk from repeated use. He clutches a folded piece of paper in his left hand, a reference to his nearly 120 existing letters, which were particularly prized in the Renaissance for their breadth of topics and revelation of Jerome's spiky personality. Jerome's eyes reveal a depth of pathos, his mouth a hint of a smile, and forehead creases indicate a life of thoughtfulness and animation. The entire scene gives a combined sense of energy and weariness typical of a long life of dedicated labor.

Though Saint Jerome was an ascetic and a monk, the artistic conventions of the Renaissance show his study overflowing with objects on high shelves that give the viewer ideas to contemplate. Half-filled carafes on the upper right symbolize the perpetual virginity of the Virgin Mary, a theological position staunchly supported by Jerome in an influential treatise. A round wooden box is topped with fruit, in itself a small tableau concerning the mysteries of sin and salvation. The fruit calls to mind the poisonous apple of Adam and Eve's fall in the Garden of Eden, the food of spiritual sickness and eternal damnation. By contrast, the round box below has been identified by scholars as a large pyx holding Eucharistic hosts, the food of salvation and the medicine of eternal life, an idea central to Jerome's thought and writings as an answer to the sin of Adam. In a similar vein, the apothecary jar with Christ's monogram — the IHS — likewise speaks of Christ as a spiritual remedy for fallen humanity.

Ancient saint, ancient texts

In Jerome's time, knowledge of Hebrew was not common in Christian circles, and he insisted upon translating the Old Testament from the Hebrew rather than the Greek translation known as the Septuagint. He consulted with Jewish scholars for both linguistic and interpretive help, often facing criticism from fellow Christians for doing so. Later centuries praised him for his intellectual rigor, and Ghirlandaio's painting is filled not only with books, but also with pieces of text on scrolls and bits of paper pinned here and there, displaying the ancient languages Jerome mastered in order to translate the Scriptures. The study of inscriptions, known as epigraphy, not only interests modern art historians, but fascinated Renaissance humanists who cherished ancient languages and learning.

A small paper on the shelf above the saint's hand reads in accurate Greek the phrase from Psalm 51: O God, have mercy on me according to your great pity. A scroll hanging from the shelf reads in partially legible Hebrew: I call out in my anguish; my lament is troubling me. These prayers of repentance and lamentation suit the monk who lived a life of penance in the desert. Yet they also reveal the saint who sought God's merciful entrance into the life of man, exemplified by the Latin inscription in the architectural frieze above the painting: "Illuminate us, O radiant light; otherwise the whole world would be dark." In one of his letters, Jerome explained that after some immoral living in his youth, pangs of conscience led him to wander the Roman catacombs, visiting the underground tombs of the martyrs and apostles. The darkness moved him to ponder the depths of hell and brought to his mind a saying of the ancient poet Virgil: "everywhere horror seizes the soul and the very silence is dreadful." Saint Jerome's entire life can be read as a response to this darkness. In his quest for understanding, he called the light of Christ into the world and shared it with others. And in his monumental work translating Scripture, he sacramentalized the divine voice, filling the silence with the Word of God.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Denis R. McNamara. "Saint Jerome in His Study." Magnificat (September, 2020).

Denis R. McNamara. "Saint Jerome in His Study." Magnificat (September, 2020).

Saint Jerome in His Study (1480), Domenico Ghirlandaio (1449–1494), Church of Ognissanti, Florence, Italy. © Domingie & Rabatti / La Collection.

Reprinted with permission of Magnificat.

The Author

Denis R. McNamara is Associate Professor and Executive Director of the Center for Beauty and Culture at Benedictine College in Atchison, Kan. He is the author of How to Read Churches: A Crash Course in Ecclesiastical Architecture and Catholic Church Architecture and the Spirit of the Liturgy.

Denis R. McNamara is Associate Professor and Executive Director of the Center for Beauty and Culture at Benedictine College in Atchison, Kan. He is the author of How to Read Churches: A Crash Course in Ecclesiastical Architecture and Catholic Church Architecture and the Spirit of the Liturgy.