How modern art became trapped by its urge to shock

- ROGER SCRUTON

Philosopher Roger Scruton reflects on the difference between original art that is genuine, sincere and truthful, but hard to achieve, and the easier but fake art that appeals to many critics today.

There are two kinds of untruth — lying and faking.

There are two kinds of untruth — lying and faking.

Anyone can lie. It suffices to say something with the intention to deceive. Faking, however, is an achievement. To fake things you have to take people in, yourself included. The liar can pretend to be shocked when his lies are exposed: but his pretence is part of the lie. The fake really is shocked when he is exposed, since he had created around himself a community of trust, of which he himself was a member.

In all ages people have lied in order to escape the consequences of their actions, and the first step in moral education is to teach children not to tell fibs. But faking is a cultural phenomenon, more prominent in some periods than in others. There is very little faking in the society described by Homer, for example, or in that described by Chaucer. By the time of Shakespeare, however, poets and playwrights are beginning to take a strong interest in this new human type.

In Shakespeare's King Lear the wicked sisters Goneril and Regan belong to a world of fake emotion, persuading themselves and their father that they feel the deepest love, when in fact they are entirely heartless. But they don't really know themselves to be heartless: if they did, they could not behave so brazenly. The tragedy of King Lear begins when the real people — Kent, Cordelia, Edgar, Gloucester — are driven out by the fakes.

The fake is a person who has rebuilt himself, with a view to occupying another social position than the one that would be natural to him. Such is Molière's Tartuffe, the religious imposter who takes control of a household through a display of scheming piety. Like Shakespeare Molière perceived that faking goes to the very heart of the person engaged in it. Tartuffe is not simply a hypocrite, who pretends to ideals that he does not believe in. He is a fabricated person, who believes in his own ideals since he is just as illusory as they are.

Tartuffe's faking was a matter of sanctimonious religion. With the decline of religion during the 19th century there came about a new kind of faking. The romantic poets and painters turned their backs on religion and sought salvation through art. They believed in the genius of the artist, endowed with a special capacity to transcend the human condition in creative ways, breaking all the rules in order to achieve a new order of experience. Art became an avenue to the transcendental, the gateway to a higher kind of knowledge.

Originality therefore became the test that distinguishes true from fake art. It is hard to say in general terms what originality consists in, but we have examples enough: Titian, Beethoven, Goethe, Baudelaire. But those examples teach us that originality is hard: it cannot be snatched from the air, even if there are those natural prodigies like Rimbaud and Mozart who seem to do just that. Originality requires learning, hard work, the mastery of a medium and — most of all — the refined sensibility and openness to experience that have suffering and solitude as their normal cost.

To gain the status of an original artist is therefore not easy. But in a society where art is revered as the highest cultural achievement, the rewards are enormous. Hence there is a motive to fake it. Artists and critics get together in order to take themselves in, the artists posing as the originators of astonishing breakthroughs, the critics posing as the penetrating judges of the true avant-garde.

In this way Duchamp's famous urinal became a kind of paradigm for modern artists. This is how it is done, the critics said. Take an idea, put it on display, call it art and brazen it out. The trick was repeated with Andy Warhol's Brillo boxes, and then later with the pickled sharks and cows of Damien Hirst. In each case the critics have gathered like clucking hens around the new and inscrutable egg, and the fake is projected to the public with all the apparatus required for its acceptance as the real thing. So powerful is the impetus towards the collective fake that it is now rare to be a finalist for the Turner Prize without producing some object or event that shows itself to be art only because nobody would conceivably think it to be so until the critics have said that it is.

Original gestures of the kind introduced by Duchamp cannot really be repeated — like jokes they can be made only once. Hence the cult of originality very quickly leads to repetition. The habit of faking becomes so deeply engrained that no judgement is certain, except the judgement that this before us is the 'real thing' and not a fake at all, which in turn is a fake judgement. All that we know, in the end, is that anything is art, because nothing is.

It is worth asking ourselves why the cult of fake originality has such a powerful appeal to our cultural institutions, so that every museum and art gallery, and every publicly funded concert hall, has take it seriously. The early modernists — Stravinsky and Schoenberg in music, Eliot and Pound in poetry, Matisse in painting and Loos in architecture — were united in the belief that popular taste had become corrupted, that sentimentality, banality and kitsch had invaded the various spheres of art and eclipsed their messages. Tonal harmonies had been corrupted by popular music, figurative painting had been trumped by photography; rhyme and meter had become the stuff of Christmas cards, and the stories had been too often told. Everything out there, in the world of naive and unthinking people, was kitsch.

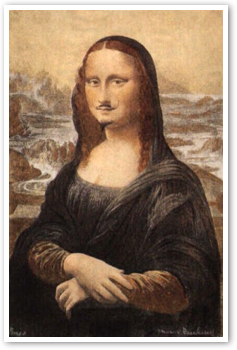

Modernism was the attempt to rescue the sincere, the truthful, the arduously achieved, from the plague of fake emotion. No one can doubt that the early modernists succeeded in this enterprise, endowing us with works of art that keep the human spirit alive in the new circumstances of modernity, and which establish continuity with the great traditions of our culture. But modernism gave way to routines of fakery: the arduous task of maintaining the tradition proved less attractive than the cheap ways of rejecting it. Instead of Picasso's lifelong study, to present the modern woman's face in a modern idiom, you could just do what Duchamp did, and paint a moustache on the Mona Lisa.

The interesting fact, however, is that the habit of faking it has arisen from the fear of fakes. Modernist art was a reaction against fake emotion, and the comforting clichés of popular culture. The intention was to sweep away the pseudo-art that cushions us with sentimental lies and to put reality, the reality of modern life, with which real art alone can come to terms, in the place of it. Hence for a long time now it has been assumed that there can be no authentic creation in the sphere of high art which is not in some way a 'challenge' to the complacencies of our public culture. Art must give offence, stepping out of the future fully armed against the bourgeois taste for the conforming and the comfortable, which are simply other names for kitsch and cliché. But the result of this is that offence becomes a cliché. If the public has become so immune to shock that only a dead shark in formaldehyde will awaken a brief spasm of outrage, then the artist must produce a dead shark in formaldehyde — this, at least, is an authentic gesture.

There therefore grew around the modernists a class of critics and impresarios, who offered to explain just why it is not a waste of your time to stare at a pile of bricks, to sit quietly through ten minutes of excruciating noise, or to study a crucifix pickled in urine. To convince themselves that they are true progressives, who ride in the vanguard of history, the new impresarios surround themselves with others of their kind, promoting them to all committees that are relevant to their status, and expecting to be promoted in their turn. Thus arose the modernist establishment — the self-contained circle of critics who form the backbone of our cultural institutions and who trade in 'originality', 'transgression' and 'breaking new paths'. Those are the routine terms issued by the arts council bureaucrats and the museum establishment, whenever they want to spend public money on something that they would never dream of having in their living room. But these terms are clichés, as are the things they are used to praise. Hence the flight from cliché ends in cliché, and the attempt to be genuine ends in fake.

If the reaction against fake emotion leads to fake art, how do we discover the real thing? That is the question I shall explore in my next two talks. 'To thine own self be true,' says Shakespeare's Polonius, 'and thou canst be false to no man'. Live in truth, urged Václav Havel. 'Let the lie come into the world,' wrote Solzhenitsyn, 'but not through me.' How seriously should we take these pronouncements, and how do we obey them?

A Point of View: How modern art became trapped by its urge to shock

A Point of View: The strangely enduring power of kitsch

A Point of View: How do we know real art when we see it?

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Roger Scruton. "How modern art became trapped by its urge to shock." BBC News (December 6, 2014).

Roger Scruton. "How modern art became trapped by its urge to shock." BBC News (December 6, 2014).

Reprinted with permission of Roger Scruton.

The Author

Sir Roger Scruton (1944-2019) was a philosopher, public commentator and author of over 40 books. He is the author of Conservatism: An Invitation to the Great Tradition, On Human Nature, The Disappeared, Notes from Underground, The Face of God, The Uses of Pessimism: And the Danger of False Hope, Beauty, Understanding Music: Philosophy and Interpretation, I Drink therefore I am, Culture Counts: Faith and Feeling in a World Besieged, The Palgrave Macmillan Dictionary of Political Thought, News from Somewhere: On Settling, An Intelligent Person's Guide to Modern Culture, An Intelligent Person's Guide to Philosophy, Sexual Desire, The Aesthetics of Music, The West and the Rest: Globalization and the Terrorist Threat, Death-Devoted Heart: Sex and the Sacred in Wagner's Tristan and Isolde, A Political Philosphy, and Gentle Regrets: Thoughts from a Life. Roger Scruton was a member of the advisory board of the Catholic Education Resource Center.

Sir Roger Scruton (1944-2019) was a philosopher, public commentator and author of over 40 books. He is the author of Conservatism: An Invitation to the Great Tradition, On Human Nature, The Disappeared, Notes from Underground, The Face of God, The Uses of Pessimism: And the Danger of False Hope, Beauty, Understanding Music: Philosophy and Interpretation, I Drink therefore I am, Culture Counts: Faith and Feeling in a World Besieged, The Palgrave Macmillan Dictionary of Political Thought, News from Somewhere: On Settling, An Intelligent Person's Guide to Modern Culture, An Intelligent Person's Guide to Philosophy, Sexual Desire, The Aesthetics of Music, The West and the Rest: Globalization and the Terrorist Threat, Death-Devoted Heart: Sex and the Sacred in Wagner's Tristan and Isolde, A Political Philosphy, and Gentle Regrets: Thoughts from a Life. Roger Scruton was a member of the advisory board of the Catholic Education Resource Center.