Caravaggio the "theologian"

- FATHER JOHN GRIBOWICH

The intimate relationship that an artist has with their work can at times seem disconnected.

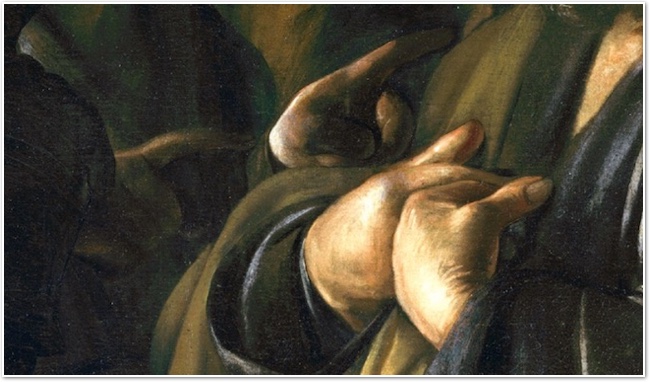

The Denial of Saint Peter (1610)

The Denial of Saint Peter (1610)Caravaggio (Michelangelo Merisi, 1571-1610),

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

This perhaps describes the relationship that Caravaggio had with his religious works.

His religious art delved into some of the most profound theology ever executed on canvas, yet his personal devotion seemed to be less than nominal. How exactly does it happen that such an "irreligious" artist can transmit theological truths? Perhaps this can only be answered by the words of Jesus himself to Pontius Pilate, heard every Good Friday in the Gospel of John: Everyone who belongs to the truth listens to my voice (Jn 18:37). An artist who taps into something transcendent belongs to the truth, and that truth is simply the Person of Jesus Christ, whether the artist realizes it or not.

Michelangelo Merisi was born outside of Milan on September 29,1571, in a small farming community known as Caravaggio. Upon moving to Rome in 1592, the painter soon became known by the town of his origin. Caravaggio found early support in Rome from families and clergy who were directly or indirectly connected to his time in northern Italy. These connections exposed him to various ecclesial traditions within Catholicism. During the time of the Counter-Reformation, a renewal of religious life blossomed among the Jesuits, Franciscans, and Augustinians. The ideas promulgated by these orders influenced Caravaggio as he transitioned from secular to religious painting.

The Brotherhood of the Little Oratory, founded and led by Saint Philip Neri (1515-1595), provided the greatest and most lasting impact on Caravaggio's theological perspective. The Oratory evolved into a community of priests and lay persons who gathered regularly for liturgical prayer, sermons and lectures, concerts, and other artistic events. All of these activities were promoted with the idea that good liturgy, preaching, and art were meant for everyone —especially the poor and the uneducated. The Oratory regularly attracted artists in Rome, and Caravaggio was no exception.

Irreligious religious art

Because of the unconventional style in which he painted and his use of "inappropriate" models and images, the first religious paintings of Caravaggio were not received well by his patrons. His artistic style embraced a heightened chiaroscuro, known as tenebrism, which imposed a stark contrast between light and darkness. His models were known prostitutes whom Caravaggio painted as saints (including the Blessed Mother!), and his frequent display of peasants with dirty feet appalled viewers and critics alike.

Yet the manner in which Caravaggio executed his religious art in itself revealed a powerful truth. The painter conveyed a radical sense of incarnational theology that emphasized the Light (Jesus Christ) shining in the darkness (the world). God fully embraced the sinful condition of humanity by becoming man in the Person of Jesus Christ. As Philip Neri sought to bring the poor, the downtrodden, and the sinner closer to an awareness of God, Caravaggio sought to bring the poor, the downtrodden, and the sinner to the awareness of the affluent and spiritually snobbish.

The Denial of Saint Peter

In The Denial of Saint Peter, the sinner who Caravaggio highlights is, of course, Peter himself. The artist masterly relates the narrative, which is found in all four Gospels (Mt 26:69-75; Mk 14:66-72; Lk 22:54-62; and Jn 18 15-18, 25-27. The faint flicker of the fire in the background situates the scene in the high priest's courtyard. The left-to-right action unfolds the charge that Peter was a disciple of Jesus. The woman pointing twice at Peter suggests the two times the maid approaches Peter (as described in the Marcan account). The presence of the soldier (who is not explicitly mentioned in any of the Gospels) heightens the suspense of the accusation. The soldier, dressed in a uniform contemporary to the artist's time, situates the current viewer in the scene and suggests that the event is diachronic in nature. His pointed finger combines with the maid's two fingers to symbolize the three denials that Jesus predicted Peter would make before the cock crowed.

Peter, on the receiving end of the charge, points to himself, in a common Caravaggio pose that seems to say, "Who? Me?" Peter's appearance also seems reminiscent of Socrates (a figure often employed by Caravaggio).

The resemblance would be an appropriate connection. Socrates was famously thought to have quipped, "I know that I know nothing," as Peter adamantly responds to his accusers, I do not know what you are talking about!

Caravaggio in the shadow of Peter

While Caravaggio succinctly captures the narrative, he more significantly captures the brokenness of Peter. One does not sense an argumentative Peter, but rather a humiliated one. Without even knowing the story, it is easy to read this painting: two people pointing at a guilty man. The enshrinement of a sinner on the canvas is Caravaggio's specialty, perhaps because the artist himself could readily identify with Peter in his wounded nature.

Caravaggio spent most of his life as a man on the run. When he left his hometown for Rome, he quickly made his mark on the art scene, only to find himself soon in trouble with the law. After murdering a man following a tennis match, he fled Rome and eventually found refuge with the Knights of Malta. While winning the favor of the Grand Master of the Knights, his erratic and volatile behavior later landed him in prison. He escaped to Naples, where he most likely painted The Denial. The work, executed shortly before the artist's untimely death at the age of thirty-eight, embodies Caravaggio's own life of paradox.

An innovative and daring painter, Caravaggio was a darling of both the aristocracy and the clergy who ultimately could not get a handle on his passions. Peter, a man also filled with passion and zeal, stumbled when that passion meant persecution and possible death. Both men belonged to the truth because they each knew their particular vocation; however, their weaknesses prove that human frailty can only be overcome by uniting one's self to the Passion of Jesus Christ.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Father John Gribowich. "Caravaggio the 'theologian'." from Magnificat (April, 2018).

Reprinted with permission from Magnificat.

The Author

Father John Gribowich is a student of art history with a specialty in Caravaggio.

Father John Gribowich is a student of art history with a specialty in Caravaggio.