Art as Prayer

- MAKOTO FUJIMURA

"The idea of forging a new kind of art, about hope, healing, redemption, refuge, while maintaining visual sophistication and intellectual integrity is a growing movement, one which finds Makoto Fujimura's work at the vanguard," writes art critic Robert Kushner. James Romaine discusses Makoto Fujimura's understanding of life and art in this interview.

|

Makoto

Fujimura |

James Romaine: Your work combines traditional Japanese painting techniques with a Western approach to abstraction. Could you describe this approach to painting as it has been traditionally practiced and how you use it?

Makoto Fujimura: My training in Japan was in a traditional Medieval technique called Nihonga. I spent six and a half years learning the technique, using materials such as malachite, azurite and other minerals mixed with animal skin glue. This method does not just go back to Japan but also the Western tradition. You will find very similar techniques in fresco painting or Medieval manuscript illumination [] I was impressed by the way Pollock took an interest in traditional sand painting and then moved from that to drip paint and to walk into the canvas as a sort of performance.

JR: Some of your works are painted in various layers of minerals that gradually become transparent over time, revealing new layers. Does that relate to your faith that God has revealed Himself over time, both in history and in your own life?

MF: Yes, each particular work has a history. The whole concept of history is based on the idea that there is a beginning and an end; it's not just cyclical. The underlying world view of Japanese art is cyclical and yet the technique lends itself to this notion that there is a beginning and an end. This technique emphasizes the process itself, how we mix paint for example, there is the mineral that is being crushed, and these minerals are then applied to the handmade paper. The artist is merging their history with that of the person who made the paper. There is this rich fabric of story being woven as you work. That is something that is very significant to me as someone who has come to understand that his world view is a premise that allows for these stories to come alive. That understanding of the world or looking at yourself, as having a history, is very Biblical. Because there is a beginning and an end, there is resolution; even in death itself there is this purpose.

JR: In addition to merging their history with that of the person who made the paper; it seems that the artist also has the privilege to participate in the story of God who made the minerals. Giving visual form to that on-going history of Creation.

MF: If you can embrace that, it clears up a huge question of purpose. I came to a point where I couldn't justify what I did, although I knew that it fit who I was as a person and the expression I was longing for. Yet when it came down to looking at this sublime grace that was flowing out of my own hands, I didn't know how to justify it. The more I thought about it, the more depressing it became. I knew that when I was making art it was very rich, very real, very refined and very beautiful. Yet I could not accept that beauty for myself. I knew that inside my heart there was no place to put that kind of beauty. And the more I painted, the more I realized that this schism between what was going on in my heart and what I was able to paint was growing larger. When I finally embraced the faith that there was this presence, this Creator behind the creation, then I had a way to accept this beauty, because I had been accepted by someone even more sublime.

|

January

Hour - Pentecost |

JR: I've heard you describe the creative process in relation to Mary Magdalene, who anointed the feet of Christ. While there is some uncertainty about who this Mary was, images of "the Repentant Magdalene" abound in Western art. But it seems to me that she is most often held up as a model for the viewer. You are the only person I've known to turn Mary around as a model for the artist. How has she been an inspiration for you?

MF: I am referring to the account in John 12 where Mary comes to the place where Jesus was staying and poured out her perfume. Here, she is the sister of Martha and Lazarus, whom Christ raised from the dead. In this state of complete and utter amazement, her heart was full of thankfulness. She was overwhelmed with emotion and she didn't know what to do. Then she realized that the only thing that she had valuable enough with which to somehow respond to this amazing miracle was this perfume, which was worth about a year's wages. She anointed Jesus with a perfume aroma that He went to the Cross with. That was the only thing He wore on His body on the Cross. She seems to me to be the quintessential artist because she responded with this intuition rather than calculation.

JR: If Mary was the quintessential artist, than Judas was the quintessential art critic. [laughter] His response to that scene was outrage and to condemn it as wasteful. I don't want to go too far with this comparison but there are many people, both Christian and non-Christian, who view the visual arts as something "extra" at best or a total waste at worst, but not essential in any way. Is there a model in the story of Mary about the value of art?

MF: Certainly. What Jesus said to her, and those around Him as well including Judas, was "she has done a beautiful thing and wherever the Gospel is preached what she has done will be remembered." That is an amazing commendation for someone like me who tends to work from the heart, who tends to work with precious and costly materials. I remember that the extravagance of Christ's love for me prompted an extravagant response. Eventually, I came to connect what I do as an artist with Mary's devotional act. Maybe that is the one act we can look to as the centerpiece for a paradigm of creativity.

JR: It seems very interesting to me that this is an example of something that at first seemed to be either wasteful or peripheral but has become enduring. In the history of Christianity and the visual art this is true as well. Many Christians today see the visual arts as peripheral to the faith but historically it has been central. Much of what we have as our tradition, the history of Christian faith, comes to us in the form of the visual arts. I could imagine being on the budget committee of a hospital in Isenheim and have to justify the wasteful expense of getting Grünewald to paint another altarpiece of the Crucifixion. But the centrality of that work to our being able to imagine the Crucifixion has endured. One could say that wherever the Gospel is preached Grünewald's image has a place. It has a value.

MF: Yes, it has a value. It takes faith to believe that. It takes faith for an artist to be able to accept that. Because you often get more criticism than affirmation. If you can believe that Christ is there in your studio, you can take risks as you act in an extravagant way that is a powerful and devotional reality.

JR: Steve Turner, the British poet and writer has said in a short text entitled Being There: A Vision for Christians and the Arts. "I've always had the conviction that Christians should be involved in the mainstream of our culture. Part of the health of our democratic society is that we debate and that there is always a vigorous discussion taking place about who we are and what truly matters. However, there is often a noticeable lack of Christian contributions to this process." Do you think that a Christian who is an artist has something particular or different to, as Mr. Turner says, "contribute to the process?" And what strategies do Christians need to take to engage the creative debate?

MF: First of all, we have to be honest about our own conditions. We as Christians are far from having perfected our own condition or having arrived at any perfection. It just shows God's grace and mercy because we tend to be the ones who are misfits. Second of all, artists of faith do need to get together to exhibit. We need to be working as a whole, as a community. Working in collaboration and pushing each other sharpens our calling and our gifts. It is the ultimate way to be able to both grieve with the world but also serve the world that needs love. New York City is full of isolated individuals who are enormously gifted and yet they have no hope. In an Art in America interview Eric Fischl spoke of four tasks artists have historically, within the Christian tradition, been asked to do: to imagine what heaven is like, what hell is like, to imagine the garden of Eden before the fall and after the fall. He notes that artists have generally become specialized and that it is rare to find an artist whose work encompasses all of these. This poses a question about our ability to show the grace of God working through us. Can we show the reality of heaven and the reality of hell? To the world they are fantasies but to us these are realities with weighty substance. These are even more weighty than the reality of what we experience today. We need to create with that understanding. I think the world is longing for artists who have the expressive range to create a picture, a vision, of where we are going.

JR: In 1997, you had an exhibition entitled Images of Grace. How does the process of making a painting, using the techniques that you do, engage the idea of grace or give weight to grace?

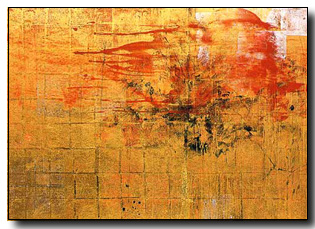

MF: The pigments I use have a semi-transparent layering effect that traps light in the space created between the pigments and between layers of gold or silver foil. This creates a "grace arena" in which light which is caught creates space. It is neither the Renaissance system of creating pictorial depth through perspective nor is it the Modernist emphasis on the surface space. It is much more similar to the stained-glass window. This approach creates the effect of space rising and falling through these veils of pigment. In Gravity and Grace, Simone Weil states that there are only two operating forces in the world, one is gravity and the other is grace. That is precisely what I am trying to do with these pigments.

JR: December Hour, a work from 1997-89, seems to have been a breakthrough work both aesthetically and also in terms of the role of faith in your work. How did that work develop?

|

Remains

of the Day 2001, Mineral Pigments, Gold on Kumohada Paper |

MF: December Hour was a unique work in that I worked on it for over a year and it was really a journey of my own heart trying to come to terms with the death of a friend and the weight of suffering. Working on it was literally a prayer each day. When I started the painting, we had talked about him coming here to New York from Japan to see the exhibition, but by the time the exhibition finally did happen he had already passed away. I had the strange experience of looking at my own work and looking at it objectively, outside of myself. I was thinking about what had happened, still somewhat in shock, and having my own work speak back to me as if to comfort my own struggle. I began to understand in finality there is this responsibility towards death. In some ways art is a way to capture that responsibility. We confront death and we struggle. We move beyond this struggle to hope. December is a month of death, but the new year is coming. I wanted to express the belief that our suffering has purpose and that there is hope.

JR: From December 1999 to February 2000, you had an exhibition at The Cathedral of St. John the Divine. How did you approach the prospect of having a visual art exhibition in that liturgical space?

MF: It was really a tremendous privilege to create works for that space, at that particular time of celebration. What was liberating to me was that as I was installing the pieces and thinking about the exhibit as a whole, I began to realize that it is a great idea to show art in a liturgical setting. One observation that I immediately made was this liberation because I didn't have to be at the center. The liturgical space already had a focal center, that is the Eucharist table. What that does for an artist is that you have this place of innocence. You can stand not at the center but at the periphery. I enjoyed it so much because I could celebrate who I was and the small role that I have but I color in the borders. I didn't have to justify my own art in that setting because it was enough to simply be who you were. It made me reflect on the exhibitions I have had in galleries in Soho or in museums. These began to seem unnatural and artificial. In these shows the artist is put in the spotlight. It may be fun but it is not what art is all about. I enjoy having openings and having people come see the work but there is still something lacking in the approach to art that these spaces represent.

JR: A group of works for the St. John the Divine project were Mercy Seat paintings. How did you arrive at those works, and did the creative process give you insights into the concept or belief of the Mercy Seat of the Ark of the Covenant?

MF: I was interested in the Ark of the Covenant because those Exodus passages, which are very significant about the nature of creativity, are so visually descriptive. While Moses was receiving the Ten Commandments, he was also receiving the instructions to build this art object, a mobile communication box and worship center. The Ark is described in such detail that we could recreate it today and it includes a blueprint of how we are supposed to approach God. There was the law, which was objective, but there also was this experiential arena which called for an intuitive response. I was inspired by this multisensory art space to create these works. These Mercy Seats were 1½ by 2½ cubits, a cubit being the measurement from the tip of the middle finger to the elbow. I was amazed to discover, after I had these boxes created, the visual movement within the pictorial field of these dimensions. As a painter, I am always trying to create dynamic movement within a field of given dimensions and a square is the most difficult because it is static. The dimensions of the Mercy Seat created a field in which there was already a powerful movement. I think it makes a statement about God's spirit even within a two dimensional space. The size is such that it doesn't dominate the viewer but it doesn't disappear either. It reveals so much about the nature of communication and prayer, with sacrifice, beauty and craftsmanship. It is a great paradigm for the artist.

JR: Another of your installations in a liturgical space was at Union Theological Seminary. Could you describe the altarpiece that you made for that space?

MF: The central panel, painted in malachite which had been heated and thus turned dark, is a Gethsemene scene with a tree. The back panel is painted with silver and crushed oyster shell white. The image is of columbine flowers which were an early Christian symbol for the Holy Spirit but which have a more recent association with tragedy and suffering. The wild columbine is a beautiful flower. In the sun their petals turn purple, but in the shade they are an almost transparent white. They are a powerful reminder of the fragility of life and also of our fallenness. In this back panel I wanted to create a place of resolution, working through the darkness to the other side. There is hope; there is purpose to suffering. Art can create a place where the weight and reality of our darkness and our dreams can be seen.

JR: Part of the history of that Chapel is that Dietrich Bonhoeffer preached there before returning to Germany and eventual martyrdom. What have his writings meant to you and your art?

MF: Bonhoeffer's writings, particularly The Cost of Discipleship, are very important to me. Of all the writings of the twentieth century, his stand out as the genuine article dealing with the question, "What does it mean to live today with faith?" He talks about "costly grace" and "cheap grace." When I paint, with the materials and techniques we discussed earlier, I am trying to depict "costly grace" in a more direct way. I realize to depict it is one thing and to live it is another. Bonhoeffer is a spiritual hero for me because he practiced what he preached. His example is more precious than anything I could create. If I could convey anything with my art, it would be express the difference between "cheap grace" and "costly grace." If I can do that, I will be pretty happy.

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

James Romaine. "Art as Prayer." In Objects of Grace (Baltimore, MD: Square Halo Books, 2000) 150-172.

This article reprinted with permission from Square Halo Books.

The Author

Makoto Fujimura was born in 1960 in Boston, Massachusetts. As a successful artist in Japan and the U.S., Fujimura has become a voice of bi-cultural authority on the nature and cultural assessment of beauty. In 1990, Mr. Fujimura founded The International Arts Movement. IAM co-hosted a major conference in New York City on the theme of The Return of Beauty in November of 2002.

On February 4th 2003 the White House announced that New York artist Makoto Fujimura had been appointed by President Bush to a six-year term for The National Council on the Arts.

Makoto Fujimura's interview after the 9/11 attacks on the world trade center, is published in Objects of Grace: Conversations on Creativity and Faith. Makoto Fujimura also has written an essay on "Form & Content" in the book It Was Good: Making Art to the Glory of God. Both books are published by Square Halo Books.

Copyright © 2003 Square Halo Books