The Hunger for Liberty

- MICHAEL NOVAK

Michael Novak shared with ZENIT the meaning of liberty, and how democracy affects political and economic liberty and the search for truth.

|

Michael Novak holds the George Frederick Jewett Chair in Religion and Public Policy at the American Enterprise Institute, where he is director of social and political studies.

He explores these ideas in his book, The Universal Hunger for Liberty: Why the Clash of Civilizations Is Not Inevitable (Basic Books).

Q: What do you mean by "liberty"?

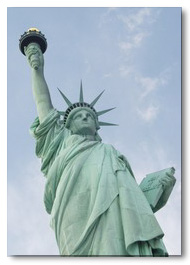

Novak: The Statue of Liberty, a gift to the United States from France in 1886, shows a serious woman as the symbol of liberty. In one of Lady Liberty's upraised hands she bears the torch of reason against the mists of passion and the darkness of ignorance, and in her other hand the Book of the Law. An old American hymn sings: "Confirm thy soul in self-control/ Thy liberty in law."

The theological background to this statue, at least as it is understood in America, is as follows. The reason the Creator created the universe is so that somewhere in it there would be at least one creature capable of receiving the Creator's offer of friendship receiving it freely, to accept or to reject.

If the gift was friendship, that gift had to be rendered in freedom. Freedom is the necessary condition for friendship between God and man, man and God. That is the theological background of the term.

But in America there is also a historical and political background. William Penn, the founder of Pennsylvania my own native state belonged to the Society of Friends, or Quakers, who wanted to build his new colony on the ideal of God's friendship extended to humans and reciprocated by humans; therefore they named its capital Philadelphia, City of the Love of Brothers.

Penn made the first article of the Pennsylvania Charter the principle of liberty. If friendship, then liberty.

Finally, there is the philosophical background. As Lord Acton put it, liberty is not the right to do whatever we please, but the right to do what we ought to do. The other animals do what they please whatever their instincts direct.

But humans have an opportunity to follow their own higher insight, understanding and judgment. Humans sense within themselves a call to use their heads to become masters of their own instincts; they are self-governors.

This is the liberty for which, when it is in its own season at last awakened, there is a universal call among human beings: The hunger to become masters of their own choices and provident over their own destiny. In this we are made in the image of our Creator. And in this, as Aristotle put it, we are made political animals, as we reason together about our common life.

Q: What is the link between freedom and truth?

Novak: The links are many. More than one chapter in The Universal Hunger for Liberty is devoted to spelling them out. In particular, as I explain in Chapter 2, a vision of "Caritapolis," or a planet of worldwide friendship, is based upon a non-relativistic conception of truth, suitable for a conversation among several truly contrary civilizations.

The first step in coming to such a vision is to approach by a kind of via negativa. Suppose there is no regulative ideal of truth that imposes itself upon all of us. In that case, if anyone who is oppressed by thugs complains of his oppression, the thugs can legitimately reply: "But that is only your opinion. In our opinion, this is what you deserve."

When the virtues proper to moral liberty weaken, so does the vitality of economic and political liberty. The cardinal virtues of honesty, courage, practical realism and self-control temperance are indispensable in democracy and a dynamic, creative economy.

The old saying "The truth shall make you free" makes a very rich point and deserves much reflection, also in practical political terms.

How do we institutionalize a conversation in which all participants are bound by a regulative ideal of truth, such that each must present evidence that may be judged by others as closer or farther from the truth, and in such a manner that all together can move forward, learning from each other, in the direction of a fuller grasp of the truth?

To participate in such a conversation means to be willing to impose the disciplines of evidence and reason upon oneself, and to remain open to the light of criticism from others and criticism also by oneself, in the light of the truth which we all are pursuing together.

If we wish to become free from our illusions, and free from false and superficial apprehensions, we need to keep making strides forward toward the light of truth. None of us wholly possesses truth; on the contrary, each of us is under judgment in the light of truth, which is greater than any of us.

Yet a love for the truth greater than our present selves may grip us and impel us forward, ever more deeply. To achieve a greater penetration of the truth about ourselves and our destiny, we need to be freed from our own self-love and illusions. In this sense, truth and freedom grow together.

Q: How does liberty in the moral-cultural sphere affect political and economic liberty?

Novak: It is the soul that animates the other two. When the virtues proper to moral liberty weaken, so does the vitality of economic and political liberty. The cardinal virtues of honesty, courage, practical realism and self-control temperance are indispensable in democracy and a dynamic, creative economy.

By moral liberty I mean the right to do what one ought to do, not what one pleases. The other animals can only obey their instincts. Humans have a right and a duty to discern among their instincts the way of reason, the law of God, and to exercise self-government in following that law down the pathways of liberty.

Q: You say that liberty and democracy require an objective moral order, but doesn't democracy undermine objective truths?

Novak: My approach to this question is dialectical, rooted in the horrific experiences of our time. Without hesitation or cavil, the Holocaust of the Hitler period is recognized as evil, and not just in somebody or other's opinion.

The United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights stands as a record, as it were, of some acts that ought never to be committed or countenanced by the civilized world. These prohibitions have been reached by a kind of via negativa, by living through certain specific evils and coming to abhor them beyond endurance, beyond tolerance.

Agreements on such matters were able to be achieved in possibly the most remarkable act of public philosophy the world has ever come to. Jews and Christians played a leading role in thinking this through. Thankfully, Mary Ann Glendon at Harvard has written a splendid study of this achievement in A World Made New: Eleanor Roosevelt and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Another line of reflection runs as follows. How can a people that cannot govern its passions in their private lives govern their passions in their public life together? There is an intimate relation between self-government in private life strong moral habits among individuals and self-government in political life.

This is the link that is corrupted by the welfare state, on the one hand, and by the cultivation of hedonism and moral fecklessness by the media, on the other hand. This moral corruption of democracy from within, in turn, corrupts intellectual life, and makes a sound public philosophy a moral philosophy unsustainable.

Fortunately, moral awakenings do occur in history. The free world is much in need of one these days. As Charles Peguy used to remind himself by a sign posted at his doorway, "The revolution is moral or not at all."

It is not democracy that undermines the search for truth, but the moral corruption of democracy from within. The fact that democracy depends on moral agency makes democracy fragile and weak. It is in need of endless vigilance and moral reawakening.

Q: What is the "clash of civilizations" and why is it not inevitable?

Novak: The clash of civilizations arises from bitter conflict, exploding in sudden violence as it did in New York and Washington on September 11, 2001. This clash was at first defined in terms of such contrary views as the meaning of truth, freedom and even God that there seemed to remain no common ground. Some could see only a long struggle to the death of one civilization or another.

To speak all too simply, by contrast, my hypothesis was that even in Muslim civilization, for which the terrorists of September 11 presumed, falsely, to speak, there was a religion of reward and punishment after death.

In short, there is plenty to discuss about truth, liberty and God among Christians, Muslims and Jews today and in the centuries to come.

As Thomas Aquinas and Moses Maimonides long ago pointed out during the golden age of Jewish, Christian and Muslim dialogue of several centuries ago, such a religion was bound to hold deep within it a theory of freedom, even if its philosophers and theologians had not yet made much of that theory, or grasped its full implications, or drawn out all its possibilities. Without freedom, reward and punishment after death make no sense.

In short, there is plenty to discuss about truth, liberty and God among Christians, Muslims and Jews today and in the centuries to come. And such a conversation can most profitably go forward under certain agreed upon rules appropriate to inquiries in the light of truth, liberty, and our poor and inadequate and yet inwardly demanding ideas about God.

When I was writing Universal Hunger for Liberty in 2002 and 2003, such a dialogue seemed nowhere in sight.

But in the express desire for liberty manifested in the elections of Afghanistan and Iraq and the still newer demand for them in Lebanon, Egypt, Iran and other Islamic cultures in the months since then the topic of freedom is very much on the universal agenda.

It is so, not only in the political sense concerning democracy, but also in the cultural and human sense what human virtues, insights and practices are essential to it?

We have begun to move in the direction of Caritapolis one painful and small step at a time, under the force of necessity. The alternative is indescribably bleak, and also unnecessary, wasteful and fraught with immense suffering for all.

Q: You seem to suppose that Islam is open to liberty. But the very word "Islam" means to submit. What makes you believe that Muslim cultures can foster liberty, given this tension between authority and liberty?

Novak: The great American poet T.S. Eliot wrote that the most beautiful line in human poetry occurs toward the end of The Divine Comedy, where Dante writes in early Italian a line that we translate succinctly into English this way: "In His will, our peace."

In Christian and Jewish thought, too, there are tensions between God's authority and human liberty, as there are between truth and liberty. These difficulties force us to deepen our own thinking and linguistic capacities, our ability to make distinctions and even our creativity in imagining solutions to seemingly insoluble puzzles.

It should be noted, too, that contemporary relativists...face immense difficulties of their own. Why do they value liberty, instead of coercion? How do they find anything to be evil, without merely stating an arbitrary preference, with which others are free to disagree?

It should be noted, too, that contemporary relativists, who face no difficulties in regard to the authority of God, in whom they have no belief, nonetheless face immense difficulties of their own. Why do they value liberty, instead of coercion? How do they find anything to be evil, without merely stating an arbitrary preference, with which others are free to disagree?

Their systematic relativism appears to turn decision-making, in the end, over to the most thuggish among them. If truth is of no relevance, the only source for resolving disagreements seems to be naked power.

In the universal dialogue among civilizations in the future, by contrast, under the regulative ideal of truth, I believe each of us will teach some lessons to others, and learn from them as well.

About the great questions of how to conceive of and speak rationally about liberty, truth and God, there is much for all of us to learn. And there is great merit in each of us plumbing as deeply into our own traditions as we can, in order to bring old and revered and still fecund treasures into the universal patrimony.

Q: It can be persuasively argued that the nations of the West have lost their desire for liberty at least the European nations have. In Europe, government expansion and new forms of cultural and social despotism are on the rise. What is the source of this trend?

Novak: One answer is the welfare state, which displaces personal responsibility from the center of the political universe and replaces it with the "caring" state the "new soft despotism" predicted by Alexis de Tocqueville in Democracy in America.

A deeper answer, perhaps, is the drama of atheistic humanism. If there is no God, what human beings do with their lives does not matter in the end. Nothing eternal is at stake nothing true or just or significant.

In a world of nihilism, or even relativism, comfort and convenience are as significant as liberty. To most people, they may be even more attractive. In Europe, it seems as if they are.

What Christianity and Judaism once contributed to European identity was a taste for the importance of how women and men use their personal liberty, either to be faithful to their God or to turn away from him. People could be unfaithful to God directly to his face, or indirectly through their betrayal of their duties to others.

At bottom, what Judaism and Christianity contributed to European identity, then, was the sharp taste of liberty the taste of true human dignity, trembling in the delicate balance of how humans decide to use their liberty.

At bottom, what Judaism and Christianity contributed to European identity, then, was the sharp taste of liberty the taste of true human dignity, trembling in the delicate balance of how humans decide to use their liberty.

As Europeans ceased to be faithful to Judaism and Christianity in the primacy of liberty, the Torah is at one with the New Testament they have lost their taste both for liberty and for the God of liberty. They have erected other, false gods.

More than we used to think, the God of Abraham, Isaac, Jacob and Jesus seems indispensable to the Western hunger for liberty. It seems empirically evident that secularism has precipitated the death of the hunger for liberty.

That is one reason why I argue that Muslims should not be pressed to pursue the path of secularism. On the contrary, we can see by the experience of the West and also the experience of Arab secular states that secularism withers liberty as winter withers the formerly green forests and fields. Secularism has no resources to arrest moral decadence, or the raw will-to-power.

The God of Abraham made women and men free. The God who created us created us free at the same time. That is the root of our hunger, our thirst, to be what we are meant to be. Liberty is a hunger and a thirst in all human creatures, even in those who have sought to still it, and kill it, in their own hearts.

Political history provides many proofs of the proposition that the hunger for liberty has a persistent historical power. The history of our own time is the most vivid lesson imaginable in the truth of this proposition.

Consider first the evidence since January 30 of this year. The courageous, ink-fingered election in Iraq followed upon the "Orange revolution" in Ukraine, which was followed in turn by the dynamic election in Palestine, the brave open demonstrations in Lebanon and yet other public demands in other nations.

Then think backward to the world of the year 1905. In many ways, the history of the 20th century was an attempt to impose tyranny in various forms upon the whole human race.

And yet, from a small handful of relatively free polities in 1905, the world has grown to well over 120 today not without world wars, not without immense struggle and not without continuing problems, but with undeniable effort, willingness to sacrifice and modest success.

Now the hunger for liberty is slowly sweeping through the Muslim world not least in the Arab countries as well as the Muslim nations of the "soft underbelly" of the former Soviet Union, the countries whose names end in "-stan."

In this sense, my book, written in 2003, has already begun to be vindicated by events. Its hypothesis and the reasons given for it seems far more in touch with reality today than they did when they were first written down. So, at least, I invite readers to verify, or to falsify.

Where I am mistaken, perhaps others can put the truth of things more exactly. I would welcome that.

Q: Does the fostering of liberty in Muslim, and other, cultures require secularism?

Novak: On the contrary. Experience shows that secularism is not a sustainable moral ecology. Secularism has no corrective to moral decadence, corruption and decline. It is parasitical on the moral ecology that proceeded the secular era, and when that original moral impulse is exhausted, what has moral relativism got to teach or even to recommend?

...one reason Rome yielded to Christianity was the superior moral power of the Christian ethic, especially the Christian conception of liberty.

Now there may be a form of secularism that is not relativistic or nihilistic. The Rome of Cicero and Seneca seemed to be of that sort, if one can call secular a culture so permeated with piety to the gods of Rome. But one reason Rome yielded to Christianity was the superior moral power of the Christian ethic, especially the Christian conception of liberty.

An analogous conception of liberty lies buried in the Islamic conception of rewards and punishments for personal actions. I would encourage and challenge Islamic thinkers to draw from their own resources a full-blown theory of liberty, both personal and political, to an extent never achieved before.

Q: How do political and economic liberties reinforce each other?

Novak: Either without the other is plainly flawed.

If all democracy brings a people is a chance to vote every so often, without any economic improvement in the conditions of the poor, the people will not love democracy. Conversely, if there is economic prosperity without protection for the civil rights of minorities, moral restlessness and even rebellion will fester.

Political liberty is restless until it ends in economic liberty, just as economic liberty soon raises demands for political liberty. In both cases, what one means by "liberty" is not license but self-government personal initiative, and also respect for the law, civil and moral. ZE05051329

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

ZENIT is an International News Agency based in Rome whose mission is to provide objective and professional coverage of events, documents and issues emanating from or concerning the Catholic Church for a worldwide audience, especially the media.

Reprinted with permission from Zenit - News from Rome. All rights reserved.

The Author

Michael Novak (1933-2017) was a distinguished visiting professor in the Busch School of Business at The Catholic University of America at his death. Novak was the 1994 recipient of the Templeton Prize and served as U.S. ambassador to the U.N. Human Rights Commission. He wrote numerous influential books on economics, philosophy, and theology. Novak’s masterpiece, The Spirit of Democratic Capitalism, influenced Pope John Paul II, and was republished underground in Poland in 1984, and in many other countries. Among his other books are: Writing From Left to Right, Living the Call: An Introduction to the Lay Vocation, No One Sees God: The Dark Night of Atheists and Believers, Washington's God, as well as The Universal Hunger for Liberty: Why the Clash of Civilizations Is Not Inevitable, The Catholic Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, Tell Me Why: A Father Answers His Daughter's Questions About God (with his daughter Jana Novak), and On Two Wings: Humble Faith and Common Sense at the American Founding. Read a more complete bio of Michael Novak here. For more information, see www.michaelnovak.net.

Michael Novak (1933-2017) was a distinguished visiting professor in the Busch School of Business at The Catholic University of America at his death. Novak was the 1994 recipient of the Templeton Prize and served as U.S. ambassador to the U.N. Human Rights Commission. He wrote numerous influential books on economics, philosophy, and theology. Novak’s masterpiece, The Spirit of Democratic Capitalism, influenced Pope John Paul II, and was republished underground in Poland in 1984, and in many other countries. Among his other books are: Writing From Left to Right, Living the Call: An Introduction to the Lay Vocation, No One Sees God: The Dark Night of Atheists and Believers, Washington's God, as well as The Universal Hunger for Liberty: Why the Clash of Civilizations Is Not Inevitable, The Catholic Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, Tell Me Why: A Father Answers His Daughter's Questions About God (with his daughter Jana Novak), and On Two Wings: Humble Faith and Common Sense at the American Founding. Read a more complete bio of Michael Novak here. For more information, see www.michaelnovak.net.