How Jefferson Honored Religion

- REV. JOSEPH KOTERSKI

The famous appeal to Natures God in the Declaration of Independence augurs well for religious believers, but a note of caution is needed as well

|

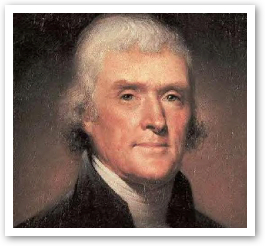

Thomas

Jefferson

(1743 - 1826) |

When Thomas Jefferson wrote of the laws of nature and nature's God in the Declaration, one may take heart at his recognition of a divine author of natural law and thus an admission that God was the ultimate source of moral authority to be invoked for the revolution being launched. But it is also well to remember that Jefferson and many of his colleagues, including Benjamin Franklin, George Washington, and Thomas Paine, were all deists, not Christians.

The God of deism is a First Cause who has created the world and instituted its immutable and universal laws. But the deist insistence on conceiving of this God as an absentee landlord intentionally precludes any hint of divine immanence or divine intervention into history. Many of the Enlightenment philosophers who took deism to heart were quite critical even of the possibility of divine revelation, let alone of Christianity's claims about the necessity of such revelation.

While the open atheism of strict deism as championed by Voltaire made little headway in America, a softer theistic form of deism tended to thrive on this soil. In the course of time this theistic deism took firm root among the American intelligentsia of the colonial period, who regarded secularized Christianity as the natural religion to which any intelligent person would subscribe. Like Jefferson's famous cut-and-paste Bible, this sort of deism rejected the supernatural elements of Christianity but kept an important place for Christian morality and always presented a sincerely religious tone.

Now, in noting such deist ideas as these among some of the Founding Fathers, we must also remember that the Declaration of Independence includes not only what Jefferson might personally have believed but also what all the signers assented to. Jefferson himself wrote in a late letter that in the Declaration he intended to express "the common sentiment of all Whigs." That is, he was so intent upon garnering common agreement in support of independence from Britain that he molded his words to express those things that everyone could agree on and not just what his fellow deists preferred to hold.

Thus, while the language about God in the Declaration should not be presumed to assert Christian doctrine, neither does it exclude Christian belief. What Jefferson wanted above all was consent, and he wrote the document for presentation to a general population that was then deeply Protestant Christian in religion. His goal was to assert a set of natural rights not created by any constitution or statute and to oppose any theory of absolute monarchy or divine right of kings. For this reason, the Declaration is not couched in the terminology of any particular religion but in language that would appeal to all humankind. In light of these considerations, what Jefferson himself might have believed is important for interpreting the document, but should not be taken as solely determinative of what the text means.

The fact that the language of the document does speak of the laws of nature and nature's God should be evidence of the American founders' openness to the truths of religion. This language serves as a reminder that religious belief should not be considered inimical to political liberty but genuinely supportive of it. Similarly, Pope John Paul II has insisted that democracy is not the only possible form of government but is particularly suited to protecting human dignity and the avenues to human development made possible by political participation in a free society.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Rev. Joseph Koterski, S.J. "How Jefferson Honored Religion." Crisis 19, no. 3 (March 2001): 35.

This article is reprinted with permission from the Morley Institute a non-profit education organization. To subscribe to Crisis magazine call 1-800-852-9962.

The Author

Father Joseph W. Koterski, S.J. is Associate Professor of Philosophy at Fordham University and Editor-in-Chief of the International Philosophical Quarterly. His areas of interest include Metaphysics, Ethics, History of Medieval Philosophy. Among his books are An Introduction to Medieval Philosophy: Basic Concepts. For The Teaching Company he has produced lecture courses on Aristotle's Ethics, on Natural Law and Human Nature, and Biblical Wisdom Literature.

Father Joseph W. Koterski, S.J. is Associate Professor of Philosophy at Fordham University and Editor-in-Chief of the International Philosophical Quarterly. His areas of interest include Metaphysics, Ethics, History of Medieval Philosophy. Among his books are An Introduction to Medieval Philosophy: Basic Concepts. For The Teaching Company he has produced lecture courses on Aristotle's Ethics, on Natural Law and Human Nature, and Biblical Wisdom Literature.