Getting Religious Liberty Wrong

- REV. RAYMOND J. DE SOUZA

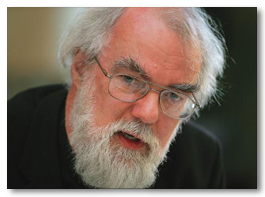

On Monday, the Archbishop of Canterbury took back what he said last week about the inevitability of accommodating shariah law in Britain.

|

In a long and complex lecture, Dr. Rowan Williams had argued that space had to be left for plural identities before the law (e.g., both British and Muslim) and therefore that some limited accommodation of shariah tribunals might be apt for Britain's growing Muslim minority. The remarks set off a conflagration over the weekend, including a public rebuke from Dr. George Carey, Dr. Williams' predecessor.

"Accommodation would lead to further demands," wrote Lord Carey. "That is absolutely inevitable, since questions to do with the separation of 'church and state' are largely new to Islam. While Christianity and Judaism recognize the truth in 'rendering unto Caesar,' it is resisted by mainstream Muslim countries. Shariah law trumps civil law every time."

Indeed, in the course of his lecture, Dr. Williams was defending religious believers in general against the real and potential tyranny of legal secularism. He employed a Christian example: the closing of Catholic adoption agencies after the government decreed that they could not operate unless they agreed to place children with gay couples. Such violations of conscience are an extension of state power beyond its competence, and perhaps Dr. Williams was attempting to think about how similar principles might be applied to Islamic communities desirous of shariah tribunals. Here, the Archbishop seems to have confused two principles of religious liberty.

First, religious liberty requires that the state not intrude upon the religious beliefs of its citizens, demanding of them what they cannot do in good conscience. The Catholic adoption agency is a case in point; the state was forcing Catholics to do what Catholic teaching cannot countenance.

As this example shows, religious freedom is generally a negative liberty; it requires the state to not restrict a set of activities. The Catholic agencies were not asking for the state to enforce religious obligations — that the children be baptized for example. (Accommodation of shariah law requires state sanction for jurisprudence which, by Dr. Williams' own acknowledgement, is rooted in divine revelation. That too is beyond the secular state's competence, if in the opposite direction.)

Second, religious liberty cannot be merely procedural, an agreement for civility's sake not to interfere with people going about their religious affairs. The classic development of religious liberty is that the state must respect what God commands, for man's relationship with God is prior to his r e l a t i o ns hi p with the sovereign or the state. Religious liberty therefore has a substantive content; it must be respected because there are certain obligations from which we cannot exempt ourselves.

How does the sovereign recognize such obligations? It is the fruit of culture, history, tradition and, above all, reason. (Hence Pope Benedict XVI's repeated insistence that faith needs reason to purify it, and reason requires faith to open it to wider horizons.) That recognition requires that a judgment must be made. If shariah law requires what is contrary to reason — what we might call political philosophy in its pure sense — then claiming religious liberty is not sufficient for the state to respect it, let alone enforce it. Today, this goes under the banner of human rights. Lord Carey's objection to shariah law is that it does not respect freedom of religion, freedom to marry, equality of women, and due process of law. He has, in short, a substantive objection to the content of shariah law.

That Christians and Muslims would disagree about the substantive content of religious freedom is not surprising — those conflicting views will significantly shape the century just now begun. It explains why Christian nations grant Muslims freedoms not available in Islamic countries without demanding reciprocity as a prior condition.

Canterbury's lecture and subsequent climb down brought forth this intervention from Downing Street: "The Prime Minister is very clear that British laws must be based on British values and that religious law, while respecting other cultures, should be subservient to British criminal and civil law."

That "subservient" has the ring of Tudor tyranny about it; since the Magna Carta guaranteed the liberty of the Church, British law has been based on the foundation that not all things should be subservient to the state. Religious liberty requires the state to respect what God requires; what God requires of the state in turn, one might say, must be in accord with reason.

That is the long fruit of Christian thought on religious liberty. Islamic thought is quite different on this point. Dr. Williams got in trouble for not explicitly siding with the Christian approach; surely a fair criticism to make against an archbishop.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Father Raymond J. de Souza, "Getting religious liberty wrong." National Post, (Canada) February 13, 2008.

Reprinted with permission of the National Post and Fr. de Souza.

The Author

Father Raymond J. de Souza is chaplain to Newman House, the Roman Catholic mission at Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario. He is the Editor-in-Chief of Convivium and a Cardus senior fellow, in addition to writing for the National Post and The Catholic Register. Father de Souza's web site is here. Father de Souza is on the advisory board of the Catholic Education Resource Center.

Father Raymond J. de Souza is chaplain to Newman House, the Roman Catholic mission at Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario. He is the Editor-in-Chief of Convivium and a Cardus senior fellow, in addition to writing for the National Post and The Catholic Register. Father de Souza's web site is here. Father de Souza is on the advisory board of the Catholic Education Resource Center.