'Everything is lost for them' — A humanitarian crisis for Armenians

- THE PILLAR

If you're an American, you might not know much about a decades-long conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, two small countries located in the Caucasus region, where Europe and Asia meet.

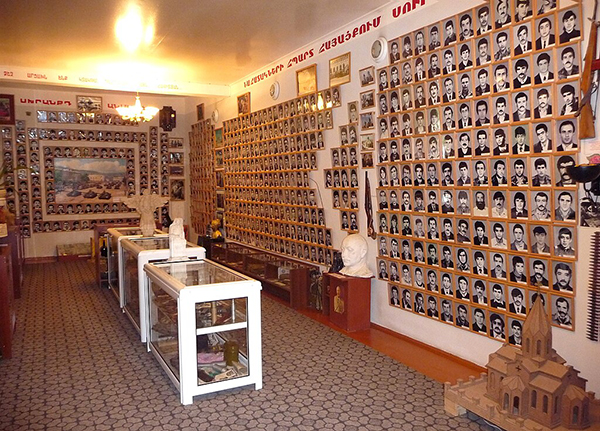

Photos of deceased Armenian soldiers in Stepanakert, Nagorno Karabakh. Credit: Ondřej Žváček via Wikimedia. CC BY SA 2.5.

Photos of deceased Armenian soldiers in Stepanakert, Nagorno Karabakh. Credit: Ondřej Žváček via Wikimedia. CC BY SA 2.5.

Azerbaijan is a majority Muslim country of around 10 million people. It is three times larger than the majority Christian Armenia, which has a population of fewer than three million.

Since the last years of the Cold War, the two countries have been locked in post-Soviet Eurasia's most enduring conflict, involving their own militaries, and that of Turkey and other regional powers.

Fighting has broken out periodically since 1998 over the disputed territory of Nagorno-Karabakh, which is situated within Azerbaijan but populated by ethnic Armenians. The area is home to the breakaway state known as the Republic of Artsakh, which is closely tied to Armenia.

An upsurge in violence began in 2020 with Azerbaijan incursion against negotiated treaties. The ensuing conflict, in which both sides used loitering munitions (also known as "kamikaze drones"), is believed to have ushered in a new era of warfare dominated by deadly autonomous machines—as seen in Ukraine today.

Hundreds of soldiers were killed in the most recent major clashes at the Armenia-Azerbaijan border in September 2022, which ended with an uneasy ceasefire.

But shortly after that ceasefire, purported environmental activists blocked the Lachin Corridor, the sole road linking Armenia with Nagorno-Karabakh. Human rights groups have said that the blockade is creating a humanitarian crisis in the disputed region—leaving 120,000 ethnic Armenians living under siege, with no electricity, and with dwindling food and medicine.

Pope Francis has for years shown concern for the crisis in the region, and this month, dispatched Cardinal Pietro Parolin to a diplomatic mission of peace in the region.

Historically, Armenia has deep Christian roots—in 301, the Kingdom of Armenia was the first country to become an officially Christian nation.

While Armenia remains a mostly Christian country, the majority of ethnic Armenians are Orthodox. But in Armenia, and scattered around the world, there are also a few hundred thousand members of the Armenian Catholic Church, a sui iuris Eastern Catholic Church in full communion with Rome.

Bishop Mikaël Mouradian is diocesan bishop for the Armenian Catholics of the United States and Canada. He spoke this week with The Pillar about the humanitarian crisis in Nagorno-Karabakh, behind the Lachin Corridor blockade.

Bishop Mikaël Mouradian. Courtesy photo.

Bishop Mikaël Mouradian. Courtesy photo.

Bishop Mouradian told The Pillar that he believes the current crisis is in continuity with a genocide of Armenians 100 years ago, which killed as many as 1.5 million people. And he said Armenians need the help of American Catholics.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Bishop, could you explain to our readers the current state of the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, as you see it? What is the situation for people living in a war zone?

The situation is this: Currently, this crisis, is I think, a continuation of the Armenian genocide of 1915.

Why am I saying that?

Because in 2020, when Turkey and Azerbaijan together attacked this region, the consequence of which is the crisis that we are living now, the president of Turkey boasted, saying that this is the fulfillment of "the mission of our grandfathers" in the Caucuses.

Can you imagine that?

This means that a genocidal mentality—to eradicate the presence of the Armenians in the Caucasus—it's not left the mind of Turkey or Azerbaijan.

To boast in saying that "we are fulfilling the mission of our grandfathers," I don't know. These people are inheriting the bloodshed or the... I don't know how to explain it … the sense or the taste for blood, and unfortunately for Armenian blood.

The thing is this, that when in 1915 they did the genocide, Nagorno-Karabakh was far away on the east, so they didn't reach Nagorno-Karabakh.

Just after the First World War, there was a little free Armenian Republic, which lasted only two years: 1918-20, I think, not more. Then it was occupied by the Red Army of the Soviet Union, and Armenia became part of the Soviet Union.

Stalin was the dictator, and from what I know, he didn't like so much Armenia.

He dismembered Armenia. He took what is now the region of Kars and Ardahan, the historical city of Ani, which used to be one of the oldest capitals of an Armenian kingdom back in the Middle Ages. He struck this off from Armenia and gave it to Turkey.

And then he struck off the north of Armenia, which is now the southern part of Georgia. But there are 26 Armenian Catholic villages in that region—there are almost 300,000 Armenians living there. And Stalin struck this from Armenia and put it into the map of Georgia.

Then for Nagorno-Karabakh, he took Nagorno-Karabakh and put it in the map of Azerbaijan, giving it an internal independence and autonomous status.

At the same time, he struck the Nakhchivan region in the south of Armenia, on the east side, which was occupied by the Azerbaijanis even until this day. Nowadays, there is not even one Armenian there, because during the Soviet regime, the Azerbaijani government did not give any jobs to the Armenians, and they were obliged to flee.

In 1991, when the Soviet Union collapsed, the Nagorno-Karabakh region, which was 95% Armenian, declared its independence, and wanted to join the Republic of Armenia. From that day, there was this war between the so-called autonomous republic of Nagorno-Karabakh and Azerbaijan.

There were so many years of war. But by 2020, at first, things had cooled down, everything was okay, and the region was flourishing.

Except that during the COVID period, everyone was preoccupied with COVID. And that's the same scenario that happened during the genocide of 1915. The entire world was preoccupied with World War I, and the Ottoman Empire saw that was the opportunity—that no one was seeing what they were doing. They organized and perpetrated the Armenian genocide.

This was the same scenario. The entire world was preoccupied with the COVID situation. We were all in our houses. We couldn't go out.

So beginning in 2020, Turkey and Azerbaijan did military exercises together in the valley in front of Nagorno-Karabakh.

Then suddenly in the autumn of 2020, this military exercise turned into an unprovoked attack on the region of Nagorno-Karabakh.

Unfortunately, during the last 20 years, Azerbaijan—with the wealth that they gained from the gas oil that they have—invested in quantities of armaments, even prohibited armaments. With the help of Turkey, the generals who planned and controlled the attack on Nagorno-Karabakh were not actually Azerbaijanis. They were three Turkish generals.

They brought from Syria and Libya Muslim terrorists, at least 6,000 of them, who participated in the war. People say that some of them were paid $2,000 a month by Turkey and Azerbaijan to participate in the war.

I know that the drones were fabricated in Turkey, and were run by Turkish people.

They used even prohibited bombs like the phosphoric bombs. If you go to Armenia, there are in the hospital still Armenian soldiers whose bodies are completely burned from the phosphoric bombs, which were prohibited internationally to be used.

[Editor's note: Azerbaijan has also accused the Armenian military of using phosphoric weapons.]

The outcome was that at least between 5,000 or 6,000 Armenian soldiers were killed. The majority of these soldiers were 19, 20, or 21 years old.

Turkey and Azerbaijan took all the surrounding parts of Nagorno-Karabakh and seized territory from Nagorno-Karabakh.

One hundred and fifty thousand people were obliged to leave their homes. I saw even people burn their own homes before leaving them, so that the Azerbaijanis would not use them.

Imagine a person who worked for 30 years, 40 years to build up his home; and then he is burning it by his own hand. As I say, 150,000 were obliged to leave. One hundred and twenty thousand only remain in Nagorno-Karabakh.

So, the war ended in 2020 with three partial agreements of ceasefire between Russia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. The understanding was that there would be this corridor that we call the Lachin Corridor—it is the sole road that connects Nagorno-Karabakh through Armenia and to the world. That's the unique way to go to Nagorno-Karabakh.

Frontlines at the time of the signing of the 2020 agreement with Azerbaijan's territorial gains during the war in red, the Lachin corridor under Russian peacekeepers in blue, and areas to be surrendered by Armenia to Azerbaijan hashed. Credit: VartanM via Wikimedia, Creative Commons license.

Frontlines at the time of the signing of the 2020 agreement with Azerbaijan's territorial gains during the war in red, the Lachin corridor under Russian peacekeepers in blue, and areas to be surrendered by Armenia to Azerbaijan hashed. Credit: VartanM via Wikimedia, Creative Commons license.

But in December of 2022, Azerbaijan occupied this Lachin Corridor, creating a humanitarian crisis.

Explain the crisis. People are effectively living under siege in Nagorno-Karabakh, right?

It began with the pretext as an ecological protest against some mining works. But then it ended up with a complete military blockade of the region, beginning April 23, 2023.

Then in the 11th of July, the Azerbaijani authorities prohibited even the International Red Cross to pass through this blockade, which means that these people who are now in Nagorno-Karabakh, 120,000 people who don't have electricity, they don't have gas, they don't have water, they are malnourished, and we don't know what will happen with them.

Among them, 30,000 children and almost 3,000 pregnant women.

Unfortunately for me, this is another page of the genocide.

It is genocide because when you kill 6,000 young men of the age of 19, 20, or 21, you are killing the future fathers of a nation.

A generation is lost, not counting the moral and psychological difficulties that the people are living in Nagorno-Karabakh.

For example, the teacher: What kind of lesson will a teacher give to a student about freedom? He will explain that God created us free. But the student is seeing that he's not free.

He cannot go out of his home to play with his friends. The children are so much traumatized that when they hear thunder, they look up to the adults just waiting for them to tell them, "Okay, it's bombing. We are going to the basement."

You see, the children are already in that mentality that if there are big blasts, it's bombing.

That's the psychological situation in which they are, these kids.

I have heard things from our people that give you—How do you say it in English? The goosebumps.

For example, a mother telling me that as her children play, they are always pretending that maybe they will have enough food, which they don't. I heard about another mother who had two children—she left them at home, because she didn't have any food. She went to another village to bring some food, but coming back, she found her two kids dead, who had starved.

Oh, these things are terrible.

Azerbaijani Checkpoint to the Lachin Corridor at the Hakari Bridge, viewed from Kornidzor, Republic of Armenia. The checkpoint was installed on April 23, 2023 in violation of the Tripartite Ceasefire Agreement that ended the 2020 war. Credit: Elisa von Joeden-Forgey via Wikimedia. CC BY SA 4.0.

Azerbaijani Checkpoint to the Lachin Corridor at the Hakari Bridge, viewed from Kornidzor, Republic of Armenia. The checkpoint was installed on April 23, 2023 in violation of the Tripartite Ceasefire Agreement that ended the 2020 war. Credit: Elisa von Joeden-Forgey via Wikimedia. CC BY SA 4.0.

Bishop, Armenia has complained that Russian-dispatched peacekeepers have not intervened to stop Azerbaijan's blockade of the Lachin Corridor, and there have been few international efforts to quell the humanitarian crisis. And yet, 120,000 people remain trapped beyond the Lachin Corridor blockade, with practically nothing. What international help is possible for the people behind that blockade?

It was the same thing during the Armenian genocide.

But back before the First World War, as Americans we created what is called the National Armenian Relief Committee, which was presided over by the influential American industrialist John D. Rockefeller, Spencer Trask, and others. Back in that time, Americans were organized and they sent help to the Armenians.

There is always some way to help. One thing that we can do or Americans can do is to speak about this. We don't hear about it in the news. I call it the forgotten war.

We don't speak about it in America because unfortunately as Armenia, and the region of Nagorno-Karabakh—we don't have natural resources to give to the world.

Azerbaijan has gas, and their gas is sent to Europe. At the same time, because they are selling their gas, they have a big income and I know that they have big investments in America. Meanwhile, Armenia doesn't have this.

For Nagorno-Karabakh, nowadays, we have to push our government to do something about the crisis.

Yes, President Biden declared something about the Armenian genocide, but it's not enough to acknowledge something. If you are seeing that this is a continuous thing, you have to take proper steps to stop it from continuing.

We should ask our government to uphold section 907 of the Freedom Support Act, which basically speaks about stop giving to Azerbaijan aid until they agree to not use offensive force against the Armenians and to stop this blockade of Nagorno-Karabakh.

And then to help these people, there are organizations that are helping.

I have a fund in our eparchy, the Armenia Fund, and I am trying to find donors to help these people.

And please understand, it's not only the people of Nagorno-Karabakh—Nowadays, there is the big risk that Turkey and Azerbaijan will attack the territory of Armenia also.

There is real fear that Turkey and Azerbaijan will attack the southern part of Armenia and take the entire south—what is the scenic region of Armenia, to connect Azerbaijan—with the Nakhchivan region and from there to connect with Turkey.

So, you will have all these pan-Turkic countries, which are Turkey, Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, these are all Turkic countries, and if they unite, mama mia! I don't know what will happen.

In 2016, when Pope Francis visited, he told believers in Armenia that in their country: "Faith in Christ has not been like a garment to be donned or doffed as circumstances or convenience dictate, but an essential part of its identity, a gift of immense significance, to be accepted with joy, preserved with great effort and strength, even at the cost of life itself." The Armenian Catholic Church is very small—most Armenians are Orthodox, not Catholic. So what is the mandate of your Church now, in the midst of this crisis?

What I am trying to do is to speak loud about it whenever I am.

At the same time, I ask the Americans to share what they are hearing or reading about Armenia.

Pope Francis in Armenia. Credit: Vatican Media.

Pope Francis in Armenia. Credit: Vatican Media.

I was a priest in Armenia for 10 years—I was the first Armenian Catholic priest to go back to Armenia after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

And I helped to establish in 1995 the Caritas Armenia, the Catholic Charities office—which began with only two people, and now has 280 people working there. At the same time, we have our eparchy for the Armenian Catholics in Armenia, and we have a seminary over there, and there are 37 Armenian Catholic villages in northern Armenia.

A lot of the 6,000 or 5,000 Armenian military that were killed during the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war are from these Armenian Catholic villages.

Last year, we helped three families to have a home in Armenia. They didn't have a place to stay, and I found some benefactors from America to help these families to have a home, a roof over their head. Or I help children for their studies in Armenia—we can organize help to children, where a family in America can support a child in Armenia to continue studies in the universities, and we help our diocese over there to organize summer camps for the kids—because these villages are very isolated, and the sole way for the children to even leave the villages is through these these summer camps that we organize.

And now we are helping the seminary over there, for the Armenian Catholics, in Yerevan, the capital city.

There are also the Immaculate Conception nuns, working in Armenia, and my own sister is a member of this congregation. They have two daycare centers in Armenia where they take care of children, and they have a center for girls' education in Yerevan.

These are girls who are coming from the villages. The majority of them are orphaned or poor girls who go to university in Yerevan, but they don't have the means to stay in Yerevan. So, the nuns have this dorm for them, and they welcome them in this center, where they give them shelter, food, and they help them to pay the tuition for the university.

At the same time, there is this social media thing, #SaveArmenia, and then the Philos Project, is doing a lot to give people updates.

Bishop, you were the first Armenian Catholic priest in Armenia after the Soviet Union collapsed. What was that experience like?

There are a lot of experiences that I had over there.

First of all, I have to say that I went there as a missionary, to preach the gospel, but I think that in some places, from what I saw, I was educated in my faith.

Just to give you an idea, for example, I heard about families that during the Soviet regime kept in secret parts of the gospel—not the entire book, just some four, five pages of the gospel of the Church.And they hid it at home, and they read it in secret.

If they were discovered, the entire family would have been sent to Siberia.

When I got to Armenia, and tried to find the Armenian Catholic churches, we learned that in 1937, Stalin with one signature closed up all the 73 Armenian Catholic churches in Armenia, and 94 priests were sent into exile in Siberia.

Not one of them survived.

Only one of them had the right to come back to Yerevan, the capital, in 1973, and he didn't have the right to go to his own village. He had to stay in Yerevan. He passed away in 1975. I went to his tomb, and I found that even during the Soviet era, people had engraved on his tombstone a monstrance, at great personal risk to themselves.

Once, I went to visit the village of Sucwalizi, in southern Georgia. I went there by car, it was a journey of five hours from where I was.

When I arrived at the village, people were waiting for me, on the road, at least one mile outside the village. They had been waiting to see a priest, after 70 years of having no priest in their village.

They had green branches in their hands, and they walked alongside my car while I was driving to the church of their village. They were singing hymns to the Holy Virgin Mary, hymns that they were learned by secret from generation to generation during the Soviet Union.

I had tears in my eyes, because I was thinking, "Who am I that, like Jesus, people are welcoming me with these green branches?"

But they were waiting because it was something special to have a priest finally again in their village. And I am humbled even now by that.

I learned about people who, for so many years, were baptizing their kids in secret at home, because they couldn't bring a priest in—and teaching these children the Our Father, to keep the faith alive.

This is the faith of the Armenian people, who are now so threatened today.

What should American Catholics pray for? If they want to have solidarity with the Armenian people of Nagorno-Karabakh, what should they pray for?

I would wish that parishes might organize a novena to the Blessed Virgin Mary, for the blockade to cease, and for these 120,000 people to have access to the essential things of life—water, medication, and food.

And also to pray that there will not be another genocide, to pray that Turkey and Azerbaijan will refrain from attacking Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh again.

I am afraid that really, we are there, we are seeing a genocide in Nagorno-Karabakh, but I am still confident that something will change, because if it doesn't change, at least for these 120,000 people, everything is lost for them.

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

The Pillar. "'Everything is lost for them' - A humanitarian crisis for Armenians." The Pillar (July 28, 2023).

Reprinted with permission from The Pillar.