The Believers

- ELIZA GRISWOLD

The death of a missionary and the world of Christian martyrdom.

|

|

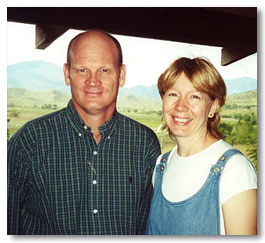

Martin and Gracia Burnham

|

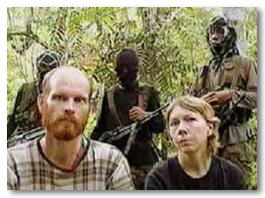

Gracia Burnham needed a backpack. Months earlier, she and her husband, Martin, had been kidnapped and dragged into the jungles of the Philippines by members of the Al Qaeda-linked Abu Sayyaf, or "Bearer of the Sword," and they had nothing in which to carry their few belongings. Until, that is, one morning when one of their kidnappers was shot and killed in the midst of a blundered rescue effort by the Filipino army. As the other militants divvied up the dead man's belongings, Gracia snatched his backpack, and she and Martin shoved in their possessions—a batik sheet, some underwear, a shared toothbrush. Gracia and Martin, both evangelical missionaries, were nearly starving: The kidnappers had kept them unfed and on the move. At various times, they had watched a male hostage led off to be beheaded or several women taken to be raped. "Abu Sayyaf thought of themselves as pious and holy," Burnham told me recently. "All this lofty chivalry crumbled before our eyes. Anything they wanted or desired, all they had to say was, 'This is jihad and the rules don't apply.'"

Suddenly, the shooting started again. Terrified, Gracia watched as the Filipino soldiers who were supposed to rescue them sprayed the open field with automatic weapons fire. Her group of fellow hostages and terrorists fled into the jungle as a helicopter bore down overhead. As she raced along the path to catch up with the others, she felt "so light," she said. She realized she had left the backpack, and all their scant provisions, behind on the trail. In tears, she told Martin how stupid she'd been. "He looked at me for a split second and said, 'I forgive you, Gracia. Now you have to forgive yourself.'"

Burnham, a 48-year-old pixie with blonde highlights, has spent much of the time since her 2001 abduction practicing forgiveness. I first met her in April at the Comfort Inn in Franklin, Tennessee. It was 6:30 in the morning, and she was dreamily eating cereal in front of the early-morning news. She hadn't needed to set an alarm clock. "God woke me up," she said, looking up from the table with dark and earnest eyes that seemed to take up most of her face. Burnham had traveled to Tennessee from her home in Rose Hill, Kansas, to attend a conference of contemporary Christian martyrdom hosted by Voice of the Martyrs, an evangelical nonprofit that has, since 1967, been "aiding Christians around the world who are being persecuted for their faith in Christ." Thanks to Gracia's generosity, I was allowed to attend the conference with her and was the only journalist present.

When Gracia's book about her ordeal in the jungle, In the Presence of My Enemies, hit the New York Times bestseller list in 2003, she became a superstar. She was born in Cairo, Illinois, and grew up as a "p.k.," or pastor's kid, deciding at an early age to become an evangelical Christian like the rest of her family. When I met her in April, only her worn, square hand holding the plastic motel spoon betrayed her life's work: For 15 years, she and her husband worked in remote parts of the Philippines as missionaries for New Tribes, a nondenominational evangelical group that focuses on planting churches among the last tribal groups who have never heard of the gospel. Before entering the field, New Tribes missionaries undergo extensive training, including rigorous language, medical, and dental skills, as well as survival tactics—New Tribes has one of the highest death rates of any mission group. In the Philippines, Martin, a pilot, delivered mail and supplies and shuttled the sick over the dense jungle; Gracia, a radio operator, home-schooled their three children, Jeff, Zach, and Mindy.

During months of hunger, fear, sleeping on the mosquito-infested ground, and hiking for hours seemingly in circles, Gracia's faith occasionally failed her. "The worst part was seeing who I really was," she said. She coveted food sent into the jungle for them, which Abu Sayyaf refused to share. She tired of praying to "a God who sometimes seemed to have forgotten us." She would say to Martin, "You know, scripture says these words: If you will ask anything in my name, I will do it.' In my situation, that verse is not true, so why is that in there?" But Martin encouraged her. "You believe it all, or you don't believe it at all," he told her gently.

"We thought that, at the beginning, the fact that we were Christian missionaries would be held against us, but we found that not to be true at all," she said. "In fact, they really admired us because Martin explained that New Tribes missions go into places where people are worshipping rocks and trees, their ancestral spirits. They're not worshipping the one true God, and we tell them who the one true God is. So they [Abu Sayyaf] felt we were kind of doing the same thing, which shocked me because we are as far from Islam as I think you can be." Her hatefulness and covetousness surprised and dismayed her, so she and Martin prayed for a way to love their captors. "We never forgot they were the bad guys," she said. "But they were also our family."

Then, on June 7, 2002, for the seventeenth time in more than a year, Filipino soldiers blasted into camp in an attempted rescue. By the time she dropped from her hammock to the ground, Gracia had been shot in the leg. Martin lay dead beside her.

|

Following his death, Martin Burnham became a modern-day martyr for many evangelical Christians, one of 70 million killed since the beginning of the faith, according to the World Christian Encyclopedia. In stark contrast to the image of Christian martyrs as a phenomenon of the ancient past—the apostle Peter crucified upside-down, or early pilgrims fed to Roman lions—the encyclopedia explains that 60 percent of those 70 million have died in the twentieth century. "People are used to the Joan of Arc type of martyrdom, an individual on trial," Todd Johnson, co-author of the encyclopedia, told me. "This is a context in which people are being killed for being Christians: In Uganda, for example, if you think of The Last King of Scotland, Idi Amin ordered his soldiers to go into Christian villages and kill everybody—men, women, and children." In a companion volume to the encyclopedia, Johnson catalogued each and every Christian martyr he could from the beginning of the faith to the present day. Flipping through the pages, he said, "Martin isn't in here yet, but he will be." After Martin Burnham's death, the number of applications to New Tribes soared, bearing out a deeper trend: Martyrdom is an effective tool of modern evangelization.

I've investigated Christian martyrdom in Nigeria, Sudan, Indonesia, Malaysia, Yemen, and Iraq, among other countries. In Mosul, at the beginning of the Iraq war, an undercover priest showed me a burnt Bible and a glass of what looked like paint chips. "This is the blood of the first martyr of Kurdistan," he said, holding up the glass. It turned out he had scraped dried blood from the floor of a Christian bookshop where one of his converts had been shot.

Today, most of us associate the word "martyr" with Islam, with boys—and sometimes girls—wearing white headbands and strapped with explosives. And, indeed, the Arabic word for martyr, shaheed, and the Greek word, martys, both mean the same thing: witness. In the early days of each embattled faith, holding fast to one's beliefs in the face of torment or persecution—witnessing—could result in death, and the Crusades made this form of faith-based brinkmanship more prevalent. But, by the late twentieth century, Islamic and Christian martyrdom have largely come to mean different things: one, a willingness to kill; the other, a willingness to die.

This was the central theme of the Voice of the Martyrs gathering, called "Enduring Faith," that I attended with Gracia one Saturday last month at the Christ Community Church in Franklin. The conference's aim was to inform those evangelical Christians who had never heard of contemporary martyrdom about the suffering of Christians around the world. Outside, pin oaks and magnolia trees with still-hard blossoms ringed the church. A steel monument that looked like a giant Exacto knife marked the entrance.

On another table was a stack of what looked like orange kitchen garbage bags covered with Asian characters I couldn't identify. The language, I was told, was Korean and the words Bible verses. The bags themselves were balloons. Since the 1960s, Voice of the Martyrs has been filling them with helium, releasing them along the border between South and North Korea, and praying that they will reach those in the North who have never heard about the Bible. (The government of North Korea reportedly orders anyone who finds these "balloons" to deliver them to the police station.)

As the conference began, there were moments of prayer for North Korea's President Kim Jong Il and Iran's President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Both North Korea and Iran lie geographically within an area where the drive to bring the gospel is especially intense. "We work mainly in the 10/40 window, the bastion of Communism, Islam, and Hinduism," Robert Brock, a mission representative for Voice of the Martyrs, said. The 10/40 window is the rectangle of land located from ten to 40 degrees north of the equator from West Africa through Southeast Asia. This plot of land, also called the "Window of Opportunity," is home to 2.7 billion people, almost half the world's population. Eighty percent of them live on $500 or less per year, and 90 percent have never heard the gospel. The 10/40 window is the last great frontier for Christian missionaries. It is also the most "resistant," i.e., ideologically opposed to evangelical Christianity. "It's the hardest place to work, my friend," Brock said. "It could cost you your life."

Not all martyrdom lies so far away, however. At breakfast that morning, I'd met Tom Zurowski, a baby-faced preacher from Albion, New York. He told me that he had first come to know Jesus one night at age 19, while sitting at the end of his bed with a hunting knife, contemplating suicide. Christ had saved his life. A recovering alcoholic and drug user, Zurowski is now the director of Global Response Network, an organization that, like Voice of the Martyrs, "aids suffering Christians as they take up their cross and follow Jesus."

Zurowski was introduced to contemporary martyrdom more than a decade ago, when a friend asked whether he would be willing to die to save the life of an unborn child. He had no answer, until he was on his knees in the street outside an abortion clinic. When a car trying to get past pushed its bumper against him, he knew he wasn't going to move. He was willing to die to stop abortion. Along with the other demonstrators, Zurowski was arrested and held in prison for several weeks. In prison, he first heard that Christian persecution was a contemporary problem.

Since then, Zurowski has made more than 40 trips overseas. On the church stage at the conference, he told the audience the story of one teenage boy he had met in southern Sudan who had escaped from slavery in the North. As a seven-year-old, the boy had snuck out of his master's house to go to church. When he came home, the irate master nailed the child's knees together and his feet to a board, saying, "Today, you worshipped infidels." Zurowski showed us a photograph of the boy: His maimed legs looked hinged like a stork's.

The most outspoken speaker was Reverend Mujahid el Masih, which is Arabic for "warrior for Christ." A former Muslim, he had been forced to flee Pakistan after converting other Muslims to evangelical Christianity. But the threats on his life have followed him here to the United States. Two weeks earlier, while speaking in Sioux Falls, Iowa, he had received anonymous letters saying that, if he preached, he would be murdered and the church would be bombed. He went ahead anyway. "Allah is not the same God as the God of the Bible," he said. "We don't need bombs to destroy terrorism, we need Bibles."

When Gracia took the church stage, her tone was markedly different. "People have called Martin a martyr," she said. "That has always bothered me." The 300 nodding heads before her stopped nodding, but she continued. For Gracia, losing Martin in the jungle was not about heroism or martyrdom. His death was merely something all Christians need to be prepared to do: "give up everything for the Lord and being willing to die for him if need be," she said. "There's no safe or easy way to be a follower of Christ."

At the break, three teenage Mennonite girls, who had driven about four hours from their home in Bagdad, Kentucky, to meet Gracia, approached the book table. The girls wore matching gingham dresses with puffy sleeves and three-button vests. Mercy Grace, who was 15, wore a small white veil, with her dishwater blonde hair pulled tightly back under it. She had decided to become a missionary three years earlier, after reading Elizabeth Eliot's book Shadow of the Almighty, which told the story of her husband, Jim, who was killed in 1956 by Ecuador's Auca Indians. (The first time I heard about Eliot, I was in the living room of Reverend Franklin Graham, known as personal pastor to George W. Bush, and Franklin's wife showed me an Auca spear like the one used to martyr Eliot.)

Mercy Grace subsequently fell in love with Gracia and her story, and her family piled into the car so she could come to the conference and meet her. As a missionary, Mercy Grace didn't know yet where she would be called to go. "I'd like her to go to a closed Muslim country," her mother said, "because people have the idea that Muslims are a lost cause." She went on, "But her daddy doesn't. He's afraid of her being in that culture." I asked Mercy Grace what she thought of dying for Christ and becoming a martyr. "It would be neat!" she said, grinning widely enough to show her braces. Her mother nudged her. She closed her mouth. "It would be a privilege," she corrected herself.

The next morning, Gracia attended a senior-citizen Bible study at the First Baptist Church in Mount Juliet, Tennessee, where she'd been invited to speak.

Fifteen frosted-haired ladies, some wearing sweaters decorated with hollyhocks, gasped as Gracia pulled a piece of stiff batik fabric from a Voice of the Martyrs white plastic shopping bag. Using her teeth, Gracia showed the class how she'd wrapped the fabric, called a malong, around her to make a changing room and a bathroom. The toilet was a theme of the weekend. "The first few times I made a mess of it and had to wait until I got to the next river to wash it," she said.

"You've washed it since you've come out of the jungle," one woman said firmly. Gracia shook her head. "If I did, it might fall apart." There was another gasp.

She then showed the ladies how the fabric served as a blanket, a backpack, and even, on one occasion, a stretcher for a 14-year-old Abu Sayyaf member named Ahmed. At first, she had loathed Ahmed for hoarding food when she had none, throwing stones at her while she bathed—fully clothed—in the river, and pushing her along the trail saying "faster, faster." As she and Martin slowly starved, Gracia prayed to find a way to love Ahmed.

One day, he was injured in a firefight and soiled himself. Gracia could see he was mortified. Thinking of her own son, Zach, who was about the same age, she took Ahmed's clothes to the river to wash them. There, she was filled with love. The last time Gracia saw Ahmed, who had been carried wounded through the jungle in the malong, like a sling, he had gone stark raving mad and was tied by the hands and feet to the walls of a hut in the southern Philippines. Someone had stuffed a sock in his mouth to keep him from screaming. She wondered aloud to the Bible study class where Ahmed was now—still crazy, perhaps, or pushing another hostage up another steep mountain path. Or, most likely, he had died and gone to hell.

After Gracia finished speaking, she and I went out into the church's hallway. "You know I don't only think that Abu Sayyaf is going to hell," she said, fixing me with her fierce and loving dark blue eyes. I understood that she was talking about me. For Gracia, absolute salvation is just that: absolute.

Several days earlier, Abu Sayyaf had beheaded seven more hostages—Christian construction workers on the island of Jolo. Because Gracia follows news from the Philippines, I thought she would have heard about this, but she hadn't. Her eyes momentarily died. "So many of the kids weren't bent on jihad," she told me. In a world of extreme poverty, Abu Sayyaf was a "career move." In the end, though, "whether they were bent on jihad or not, all those guys wanted was to die in a gun battle so they could bypass the judgment of God and go straight to paradise," she explained. "If they couldn't die in jihad, their next choice was to go to America and get a good job."

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Eliza Griswold. “The Believers.” The New Republic (June 4, 2007).

This article is reprinted with permission from The New Republic.

When The New Republic was founded in 1914, its mission was to provide its readers with an intelligent, stimulating and rigorous examination of American politics, foreign policy and culture. It has brilliantly maintained its mission for ninety years.

Know more about the issues and subjects that are important to you, each week—things that you don't find elsewhere. Subscribe here.

|

The Author

Eliza Griswold is currently a Nieman Fellow in journalism at Harvard University. Her first book of poems, Wideawake Field, has just been published.

Copyright © 2007 The New Republic