Persecuted in Pakistan

- JOHN PONTIFEX

As I picked my way along a narrow walkway, I had to cup my hand over my mouth to block the stench.

At various intervals, the path that threaded among simple brick dwellings disappeared and revealed the sewer underneath. Here in the Christian quarter of a village in Punjab, Pakistan’s most populous province, we were accompanying the parish priest on his sick rounds. At one doorway, we stopped and he entered. A crowd gathered round and as we peered through the door, the whole family stood with the priest as he offered a solemn blessing over the sickbed, while its occupant was deep in prayer.

Whispering to me as we left, the priest said: “I have to visit. It’s the only thing that seems to lift their spirits. In any case, when they get ill, they don’t call a doctor. The first thing they do is to call a priest and only then will they think about getting medical help.” A scene that could come straight from the pages of an 18th-century English clergyman’s diaries is a snapshot of modern-day life in Pakistan.

About 85 percent of Christians in Pakistan live in the villages. The large number of Christians — up to three million — belies their largely invisible status in a country that is at least 95% Muslim. Even the gas stations have mosque “prayer rooms.”

An Islam that echoes through the air — especially at prayer time — also explains why a Christian born into poverty will almost inevitably die poor, too. Most work as domestics, cooks or — more likely — as labourers at brick kilns or in the huge fields of cotton and wheat that spread far and wide. They face huge problems obtaining identity cards, making it very difficult for them to get on the voters’ list or to gain access to health care and other state benefits.

Pakistan is dominated by a form of Islam that tends to view outsiders with suspicion if not contempt. As priests, sisters and lay people frequently said to us during our three weeks in Pakistan: “We know we’re not wanted here.”

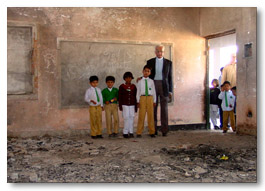

This means that Christians are dangerously at risk from laws with the severest of penalties. One such Christian is Yusif Said, who was at the centre of one of the biggest religious disturbances in Pakistan’s history. Last November, Yusif, a 46-year-old man from Mosquito Colony, Sangla Hill was falsely accused of breaking Article 295-B of the Blasphemy Law after a row over a game of cards. His alleged crime was to have burned pages containing the Koran; his sentence if found guilty would be life imprisonment. His accuser went on to call successfully on local imams to take action against the whole Christian community. The result was that 3,000 men, many of them bussed in from outside the town, ransacked Sangla’s Christian quarter, burning two churches and their adjoining presbyteries, schools and hostels.

|

Mass on Ash Wednesday at Faisalabad Cathedral |

Tearful throughout an interview, Yusif made it clear that if he changed his religion the charge would have almost certainly been dropped and that he would be able to walk away a free man. Now, even though a group of Christian lawyers successfully fought his case, Yusif must remain in a safe house. The support given to him by organizations such as Aid to the Church in Need, which I represented while in Pakistan, will prove crucial for his future well-being. If Yusif stepped outside, the fear is he would be killed. The fact remains that, regardless of the outcome of the court case, Yusif is a guilty man in the eyes of the Islamists.

The situation would have been even worse if he had broken another article of the Blasphemy Law, 295-C, which states that insulting the Prophet Muhammad is worthy of death. In the 20 years since the introduction of the Blasphemy Law, the courts have dealt with 900 cases, a disproportionately high number of them involving Christians.

What increasingly makes matters worse for Christians is the perceived link between them and the Western world, which is now being demonized by extremists. Unable to hit out at the West, some Pakistani Islamists take out their wrath on the local Christian population. This happened recently with the row over the Danish cartoons depicting the Prophet Muhammad. In Pakistan, at least three churches were burned, and countless other Christian buildings came close to suffering the same fate.

So has this set back the cause of inter-faith dialogue? I asked Bishop Joseph Coutts of Faisalabad, who spoke of continuing dialogue with Muslims in his large diocese, telling how at one such meeting one Islamic leader interrupted another and told him not to confuse the blasphemous cartoonists with Christians, particularly those in South Asia. Hence, said Bishop Coutts, when anti-cartoon fury spread, the backlash against Faisalabad Christians was comparatively small.

To an outsider, Christian practice in Pakistan comes across as being influenced by Islam in its best and most spiritual forms. Churches are often quite bare, with people seated on the ground, and the Missal is sometimes placed on a book rest similar to the type used for the Koran. Thus, in some sense the similarity of certain beliefs uniting Muslims and Christians — such as the emphasis on the Virgin Mary and Abraham — is given outward expression. Away from the headline-grabbing incidents of persecution against Christians are the lesser-known stories of how individual Muslims approached church communities affected by aggression and said their faith had nothing to do with that of the Islamists. Recalling the many such incidents of this kind, the bishops are fanning the hopes that these softly spoken words represent the voice of the majority.

For a church rocked by a wave of persecution, bonds of compassion as well as faith and practice could well prove crucial in the search for inter-faith harmony.

![]()

Aid to the Church in Need

|

A universal pastoral charity of the Catholic Church, with over 5,000 projects in Eastern Europe and throughout the world, Aid to the Church in Need (ACN) was founded on Christmas Day 1947 to help those suffering or persecuted for their Faith.

Today Aid to the Church in Need is present wherever it is most needed, from the bleak villages of Siberia, to the underground Church in China: seminarians are trained, priests and religious supported, churches and chapels are built and restored, religious programmes are broadcast on radio and television, Bibles and religious literature are printed, refugees are helped the world over. ACN receives no government grants and relies only on the generosity of its supporters. Visit the Aid to the Church in Need (U.K.) web site here, Aid to the Church in Need (Canada) here. Donate to ACN in the United States here. Donate to ACN in Canada here.

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

John Pontifex. “Persecuted in Pakistan.” The Tablet (March 20 2006).

This article is reprinted with permission from The Tablet.

The Author

John Pontifex is head of press and information for Aid to the Church in Need (U.K.).

Copyright © 2006 The Tablet