High Noon at Sunrise Rock

- CHRISTOPHER LEVENICK

If Buono v. Norton stands, the distance between the cross at Sunrise Rock and the headstones at Arlington National Cemetery will have effectively disappeared. It is only a matter of time until someone visits that field of heroes and takes offense at all the religious symbols inscribed in marble.

|  |

Sunrise

Rock | Arlington

National Cemetery |

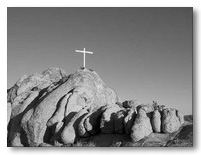

Just west of the California-Nevada border, 11 miles south of the freeway that connects San Diego with Las Vegas, a small hill rises above the sun-baked floor of the Mojave Desert. Atop that hill stands a six-foot cross, fashioned out of four-inch-diameter steel pipe. That dusty hilltop and its lonely marker just might become the scene of the most significant church-state controversy since last year's fight over the Pledge of Allegiance.

In 1934, a gritty prospector named J. Riley Bembry gathered a couple of his fellow World War I veterans at Sunrise Rock. Together they erected the cross, in honor of their fallen comrades. The memorial has been privately maintained ever since, with small groups still occasionally meeting to remember the nation's veterans.

A wrinkle developed in 1994, when the federal government declared the surrounding area a national preserve. With the cross now located on newly public land, the memorial soon caught the attention of the American Civil Liberties Union. Working with Frank Buono, a retired park ranger turned professional activist, the ACLU demanded that the National Park Service tear down the cross.

Mr. Buono insists that his seeing the monument ("two to four times a year") violates his civil rights. A federal district court found in his favor, and the decision was subsequently upheld by the Ninth Circuit. Last-ditch attempts to deed Sunrise Rock over to the local Veterans of Foreign Wars were struck down in April. Defenders of the memorial hope to appeal, but their options are narrowing.

The ACLU, however, has made out quite nicely. Not only has it prevailed in the courts to date, but it has managed to pocket $63,000. Owing to a quirk in civil-rights law, the taxpayer once again ended up paying the ACLU for pressing a highly controversial church-state lawsuit.

The Civil Rights Attorney's Fees Award Act of 1976 specifies that anyone bringing an even partly successful civil-rights suit may have the plaintiff pay all legal fees for both parties, a discretionary award that is routinely granted. Such fee-reversals are not permitted to successful defendants. Congress meant for the law to help citizens with little or no money, but since then wealthy and powerful organizations have perverted that intention. They use the specter of massive attorney fees to force their secularist agenda on small school districts, cash-strapped municipalities and, now, veterans' memorials. According to Rees Lloyd, a former ACLU staff lawyer, such litigation is "manifestly in terrorem," intended to terrify defendants into settling out of court.

And what if the defendants don't knuckle under? For advocacy groups that use staff or volunteer lawyers as plaintiffs' counsel, the result is pure gravy. If they lose their cases, they have lost no money. If they win, defendants pay attorney's fees at the private sector's market rate, which the advocacy groups can keep for themselves.

Working to amend the Attorney's Fees Award Act is Rep. John Hostettler, a Republican from Indiana. Yesterday, he reintroduced the Public Expression of Religion Act, under which plaintiffs could still ask the courts to prevent governmental endorsement of religion but could no longer soak the public for the privilege of being sued.

By eliminating the financial incentives for advocacy groups to take on trivial church-state cases, the measure would actually help restore the civil-rights law to its intended purpose. Equally important, it would signal that Congress is exercising its duty to correct the judicial branch when it goes astray of the Constitution.

Such is clearly the case here. If Buono v. Norton stands, the distance between the cross at Sunrise Rock and the headstones at Arlington National Cemetery will have effectively disappeared. It is only a matter of time until someone visits that field of heroes and takes offense at all the religious symbols inscribed in marble. Then the courts will have a hard time devising a principle by which those thousands of crosses on federal land are not as unconstitutional as the one in the desert.

Undoing the unholy mess the courts have made of the Establishment Clause will be the work of many years. In the meantime, Congress should at least deter those who would rather destroy veterans' memorials than allow them any religious symbols whatsoever. As Memorial Day approaches, swatting their hand from the taxpayer's pocket is a good place to start.

This is Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Christopher Levenick. "High Noon at Sunrise Rock." The Wall Street Journal (May 27, 2005).

Reprinted from © 2005 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

The Author

Mr. Levenick is the W.H. Brady doctoral fellow at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington.

Copyright © 2005 Dow Jones & Company, Inc