A Craven Canterbury Tale

- ANNE APPLEBAUM

Is this a storm in a teacup, as the archbishop now claims?

Reprinted with permission from Washingtonpost.Newsweek Interactive Company and The Washington Post.

|

|

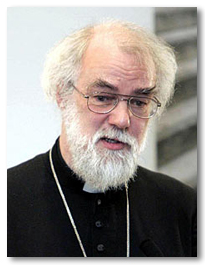

Under fire: Archbishop of Canterbury

Dr Rowan Williams |

Was the "feeding frenzy" biased and unfair? Certainly it is true that, since Thursday, when Rowan Williams — the archbishop of Canterbury, spiritual leader of the Church of England, symbolic leader of the international Anglican Communion — called for "constructive accommodation" with some aspects of sharia law, and declared the incorporation of Muslim religious law into the British legal system "unavoidable," practically no insult has been left unsaid.

One Daily Telegraph columnist called the archbishop's statement a "disgraceful act of appeasement"; another called it a "craven counsel of despair." An Observer columnist eruditely wondered whether the archbishop's comment might count as a miracle, according to David Hume's definition of a miracle as a "violation of the laws of nature," while the notoriously sensationalistic Sun launched a campaign to remove the archbishop from office.

Feebly, the archbishop's supporters have tried to defend him, reporting that he is "completely overwhelmed" by the hostility and "in a state of shock." Arguing that his remarks were misunderstood, misinterpreted and taken out of context, his office even took the trouble to publish them, in lecture form and the radio interview version, on his official Web site. I highly recommend a closer look. Reading them, it instantly becomes clear that every syllable of the harshest tabloid criticism is more than well deserved. The archbishop's language is mild-mannered, legalistic, jargon-riddled; the sentiments behind them are profoundly dangerous.

What one British writer called the "jurisprudential kernel" of his thoughts is as follows: In the modern world, we must avoid the "inflexible or over-restrictive applications of traditional law" and must be wary of our "universalist Enlightenment system," which risks "ghettoizing" a minority. Instead, we must embrace the notion of "plural jurisdiction." This, in other words, was no pleasant fluff about tolerance for foreigners: This was a call for the evisceration of the British legal system as we know it.

I understand, of course, that sharia courts vary from country to country, that not every Muslim country stones adulterers and that some British Muslims volunteer to let unofficial sharia courts monitor their domestic disputes, which is not much different from choosing to work things out with the help of a marriage counselor. But the archbishop's speech actually touched on something far more fundamental: the question of whether all aspects of the British legal system necessarily apply to all the inhabitants of Britain.

This is no merely theoretical issue, since conflicts between sharia law and British law arise ever more frequently. One case before the British court of appeals concerns a man with learning disabilities who was "married" over the telephone to a woman in Bangladesh.

Though British law recognizes sharia weddings, just as it recognizes Jewish or Catholic weddings, this one, it has been argued, might be considered so "offensive to the conscience of the English court" that it cannot be recognized — unless, of course, the fact that the marriage is legal under Bangladeshi sharia law is the most important consideration. Meanwhile, police in Wales are dealing with an epidemic of forced marriages, honor killings remain a perennial problem, and British law has already been altered to accommodate "sharia" mortgages. The archbishop is absolutely right in his belief that a universalist Enlightenment system — one in which the legitimacy of the law derives from democratic procedures, not divine edicts, and in which the same rules apply to everyone living in the same society — cannot easily accommodate all of these different practices.

Many explanations for the archbishop's statements have already been proffered: the weakness of the Church of England, the paganism of the British, the feebleness of Williams's intellect, the decline of the West. At base, though, his beliefs are merely an elaborate, intellectualized version of a commonly held, and deeply offensive, Western prejudice: Alone among all of the world's many religious groups, Muslims living in Western countries cannot be expected to conform to Western law — or perhaps do not deserve to be treated as legal equals of their non-Muslim neighbors.

Every time police shrug their shoulders when a Muslim woman complains that she has been forced to marry against her will, every time a Western doctor tries not to notice the female circumcisions being carried out in his hospital, they are acting in the spirit of the archbishop of Canterbury. So is the social worker who dismisses the plight of an illiterate, house-bound woman, removed from her village and sent across the world to marry a man she has never met, on the grounds that her religion prohibits interference. That's why — if there is to be war between the British tabloids and the archbishop — I'm on the side of the Sun.

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Anne Applebaum. “A Craven Canterbury Tale.” The Washington Post (February 12, 2008): A19.

This article is reprinted with permission from The Washington Post. All rights Reserved.

The Author

Anne Applebaum is a columnist and member of the editorial board of the Washington Post. Her husband, Radek Sikorski, is a Polish politician and writer. They have two children, Alexander and Tadeusz. Anne Applebaum's first book, Between East and West: Across the Borderlands of Europe, described a journey through Lithuania, Ukraine and Belarus, then on the verge of independence. Her most recent book, Gulag: A History, was published in April, 2003 in America and Britain. The book narrates the history of the Soviet concentration camps system and describes daily life in the camps. It makes extensive use of recently opened Russian archives, as well as memoirs and interviews. Gulag: A History won the 2004 Pulitzer Prize for non-Fiction.

Copyright © 2008 Washingtonpost.Newsweek Ineractive and The Washington Post