A Black Man in Baseball's White World

- FR. RAYMOND DE SOUZA

Sixty years ago, the Brooklyn Dodgers new first baseman went 0-3, grounding out to third, flying out to left and hitting into a double play.

|

|

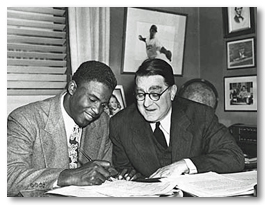

Jackie Robinson & Branch Rickey

|

He would play 150 rather more successful games that season, and be named National League Rookie of the Year for 1947. He went on to play 1,231 more games over the next nine seasons, concluding a Hall of Fame career in 1956, with over 1,500 hits and a career .311 batting average. But no game would be more important than his hitless debut on April 15, 1947.

This Sunday, Major League Baseball will celebrate the 60th anniversary of Jackie Robinsons first game, the day when the colour barrier was broken. Robinson was the first black player in Major League Baseball, which has been patting itself on the back ever since for desegregating the game before legislation required it, before the courts demanded it and before the civil rights movement made it inevitable.

Ten years ago, on the 50th anniversary of Robinsons first game, the Major Leagues retired his No. 42 jersey, for every team in baseball. Having done that, all that was left to do for the 60th anniversary was to temporarily un-retire it. So this Sunday, one player on each team will wear No. 42 in his honour, and the Dodgers now of Los Angeles, having moved 50 years ago from Brooklyn will pay tribute to Robinson by having everyone on the team wear No. 42. By the time the 70th anniversary rolls around, no doubt every player in baseball will be wearing No. 42.

There is something that does not quite fit about the posthumous adulation baseball heaps on Jackie Robinson. He certainly deserves it, but when he died in 1972 he was angry at baseball, and indeed, disillusioned with America as a whole. He did not fit the preferred overcoming-racial-bigotry storyline, the Mandela-esque former victim overcoming a lifetime of oppression, holding no grudges, forgiving those who trespassed against him.

Jackie Robinson held grudges, and he had a long list of people who had trespassed against him. Indeed, he was chosen for the role of black pioneer by Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey precisely because he was tough and feisty. Robinson believed in fighting back, not turning the other cheek. Rickey would ask him to fight another way.

Mr. Rickey, are you looking for a Negro who is afraid to fight back? Robinson would write in his autobiography, about the conversation in which Rickey first proposed that he might play in the Major Leagues. Rickey was insistent that the noble experiment of blackball players would fail if the first one exploded at the racism that would come his way. Rickey understood something about the persuasive techniques of non-violence, and the superior courage it requires.

Robinson, replied Rickey, I am looking for a ballplayer with guts enough not to fight back.

Robinson accepted Rickeys offer, and Rickeys logic. He had guts enough not to fight back. Soon he won over baseball fans, and by the end of his career he was a celebrated champion, not a cultural novelty.

But all that not fighting back took its toll. After his retirement from baseball, Robinson would enter the Hall of Fame, become successful in business and dabble in liberal Republican politics. By all measures a success, his story nonetheless was not one of reconciliation and racial harmony, but endurance and embitterment.

Endurance is not a small achievement, and Jackie Robinson knew better than anyone else that he deserved the accolades that have now come his way. But he never forgot, nor stopped reminding others, that he earned those accolades only because of the reality of racism. Robinson knew that racism was destructive of ones dignity and peace. Great souls can overcome the damage. Robinson was not one such; he endured it, he even thrived in spite of it, but he never escaped the mark it left upon him.

Until his death, he criticized baseball for the lack of black managers and administrators. He was so convinced that he always remained a black man living in a white world that he would not sing the American national anthem or salute the American flag.

They will sing the anthem and fly the flag for Jackie on April 15. Robinson deserves his celebration, but after the gauzy feel-good tributes are over on Sunday, it would be good and truthful to remember the reality of what racism does, and that in Jackie Robinsons case, the damage done lasted long after his first game 60 years ago.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Father Raymond J. de Souza, "A black man in baseball's white world." National Post, (Canada) April 12, 2007.

Reprinted with permission of the National Post and Fr. de Souza.

The Author

Father Raymond J. de Souza is chaplain to Newman House, the Roman Catholic mission at Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario. He is the Editor-in-Chief of Convivium and a Cardus senior fellow, in addition to writing for the National Post and The Catholic Register. Father de Souza is on the advisory board of the Catholic Education Resource Center.

Father Raymond J. de Souza is chaplain to Newman House, the Roman Catholic mission at Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario. He is the Editor-in-Chief of Convivium and a Cardus senior fellow, in addition to writing for the National Post and The Catholic Register. Father de Souza is on the advisory board of the Catholic Education Resource Center.