Pope John Paul II's Teaching on Women

- MARY ROUSSEAU

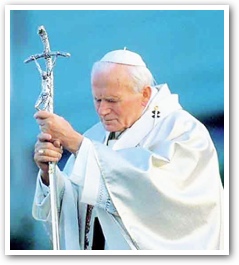

John Paul IIs vision of the dignity and vocation of women is one of the most exciting events of our era, writes Mary Rousseau, who provides an inspiring overview of that vision.

|

My thanks to all who had a hand in organizing this conference honoring the Catholic woman, and especially to whoever put me first on the program and then assigned me a topic that simply can't miss. For Pope John Paul II's vision of the dignity and vocation of women is one of the most exciting events of our era. When I look at my materials for this presentation, I am moved to say what Dryden said of Chaucer: "Here is God's plenty!" I'm also grateful for being first today when I look at the names of the women who are to speak after me; believe me, any one of them would have been a tough act to follow.

As to our theme, honoring the Catholic woman, to honor someone is to confer high public esteem upon him. It presupposes the dignity of its recipient; dignity being an excellence that rightly commands esteem. It is right, then, that we begin with Pope John Paul II's vision of the excellence on which we seek to confer our public esteem today. For despite all that has been said recently about women, about human fulfillment and human sexuality and roles in Church and society, there is a fundamental advance in this philosopher-pope's teaching. Indeed, it enables us to dispose at once of any apparent anomaly in the fact that eight Catholic women are speaking today. We might appear to be in the embarrassing position of honoring ourselves. But such is not the case. For the Catholic women who are being honored today are those who truly have the dignity described by the Holy Father. That dignity is not mere birth and maturity as women, coupled with Catholic baptism. It is nothing less than genuine feminine holiness, a gift which none of us would dare to claim as her own.

The primary source for Pope John Paul II's teaching on women is, of course, his Marian year meditation, the letter On the Dignity and Vocation of Women (DVW). [1] I propose to interpret its basic theme in the light of other papal and ecclesial writings, notably Love and Responsibility, [2] the Lenten talks on Genesis, [3] the encyclical, The Role of the Christian Family in the Modern World [4] and the pamphlet deploring the new reproductive technologies, Respect for Human Life [5] The Holy Father affirms the strict equality of women with men in the dignity of being persons. Our equality, in fact, is a religious equality, the deepest equality of all. It is revealed chiefly in two places: the Adam and Eve story in Genesis and the accounts of Jesus' many conversations with women in the Gospels. But our personal dignity is differentiated sexually. And so, equality is not sameness, and difference is not inequality.

Thus we shall begin with the general notion of universal human or personal

dignity and then see how that dignity is particularized in the female sex. Once

having established the distinctive human dignity of women, we shall make some

assessments of the women's movement in our country. For contrary to his bad press,

Pope John Paul II has a very good understanding of our American culture. DVW

applies almost item-by-item to the American feminist agenda. Along the way we

shall also see that this celibate male, so widely accused of having no compassion

for women, has in fact a compassion for us that is exquisite and deep.

The religious equality of men and women is clear from the creation of Eve as Adam's helpmate, a helpmate precisely in the task of being a person. That task required another person with whom a "unity of the two" might be formed, so that man, precisely as such a unity, might be in the image and likeness of God (DVW, pp. 22-25). Adam recognized Eve's religious equality with himself in the joyous cry with which he greeted her, "Bone of my bone and flesh of my flesh!" (Gen 2:23).

Men and women thus have a common dignity and vocation, a kind of fulfillment that is possible only to persons: the communio personarum, or communion of persons, that mysterious way in which we can be truly one with each other and still find our individual identities intact and even enhanced. This communion is the theme of almost everything that Pope John Paul II has written or spoken, dating back to his days as a professor of ethics at the University of Lublin. It is, in fact, holiness, our communion with the Divine Communion of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. It is the grace by which we participate in the inner life of the Trinity. The common call to men and women, then, the dignity of the vocation that we share, is the call to holiness.

Jesus recognized this religious equality in all his encounters with women, where his behavior was startlingly countercultural. Contrary to all the customs and traditions of his time, he spoke to women, in public and about the most serious matters of human life: the identity of the Messiah, resurrection, the meaning of his own death. He was the first to call Jewish women "daughters of Abraham". He made women the primary witnesses of his death and the first to know of, and tell the men about, his Resurrection. Such dignity had never before been accorded to women (DVW, pp. 46-60).

This theme of a common human vocation to holiness in a communion with each other that is also a communion with the Divine Communion weaves through the nine chapters of the letter On the Dignity and Vocation of Women. Chapter I sets the meditation in the context of the Marian year (I, "Introduction", sections I and 2). It is followed by a treatise on Mary, the paradigm of the dignity and vocation of women (II, "Woman Mother of God", sections 3-S). The next two chapters constitute a Christian sexual anthropology (III, "The Image and Likeness of God", sections 6-8, and IV, Eve-Mary", sections 9-I I). Chapter V, "Jesus Christ" (sections I2-I6) is a breathtaking phenomenology of the countercultural behavior of Jesus toward women. Chapter VI ("Motherhood-Virginity", sections 17-22) returns to Mary as the epitome of feminine dignity and the model for all men and women in all interactions and relationships. Chapters VII ("The Church — the Bride of Christ", sections 23-27) and VIII ("The Greatest of These Is Love", sections 28-30) draw important practical conclusions about the roles of women in Church and society. The last chapter (IX, "Conclusion", section 31) is a prayer of thanksgiving to the Holy Trinity as Creator, Redeemer, and Sanctifier of women, for all the "fruits of feminine holiness" throughout the centuries.

We can select from these riches only one or two nuggets. The theme of the communion of persons appears in section 5, "To Serve Means to Reign". Here the Pope describes the psychology of Mary's fiat, spoken by one who was both a paradigm and a unique individual woman. God invited her to become the virgin Mother of God. He did not command her, but sought her informed consent. Mary, with her integral freedom, said, "Be it done unto me according to thy word." She thus accepted her individual vocation within the universal human vocation: self-fulfillment in a communion of persons which is also a communion with the Communion of Divine Persons in the Blessed Trinity. She achieved, as Virgin and Mother, the feminine holiness that is the dignity and vocation of women (DVW, pp. 14-I9).

Many years earlier, as a professor of ethics, Karol Wojtyla had found this communion of persons in his primary philosophical source, the treatise on love in the Summa Theologiae of Saint Thomas Aquinas, [6] and made it the thesis of his masterly Love and Responsibility, [7] Aquinas offers a simple but profound truth: we humans, who need fulfillment simply because we are limited, needy, deficient, in our very being, can find fulfillment only through union with what is other than ourselves. And that union can come in only one way: through a very special kind of love whose name is amor amicitiae. The term, a noun modified by an adjective that has the same root, has no English equivalent. Pope John Paul II calls it "self-giving love" in his letter on women and contrasts it (as does Aquinas) with its opposite, amor concupiscentiae, which the Holy Father calls "desire". The first of these is love in the truest sense of the term, genuine or perfect love, in comparison to which desire and all other kinds of love are deficient. For self-giving love constitutes the communion of persons. Desire, on the other hand, does not, and cannot, do so. [8]

To love is, in every case, to wish some good to someone, that is, benevolence.

But we can exercise benevolence in two ways, depending on our motivation: we can

wish a good to someone, a beloved, for that beloved's sake, or for our own. Thomas

Hobbes' example is very enlightening: he once gave money to a beggar, not in order

to relieve the poor man's misery, but to relieve his own discomfort and guilt

— to feel better about himself, we might say. [9]

His love was desire. Although Hobbes wished a good to another, it was his own

good that was the center of his concern. Such egocentric love does not unite a

lover to the person loved, simply because the focus of concern in such transactions

is the self. Desire does not reach out to form a bond with another. It leaves

us where we begin, still locked into our original limited being.

Self-giving love, on the other hand, wishing a good to another for that other's sake, does bring about a communion of persons. For when we wish a good to another person for that other person's sake, our love is centered precisely on that other's being, his well-being. In such altruistic loving, we do reach beyond ourselves and extend our own being, for we identify the good of another as our good, too. We thereby possess it as our own. Had Hobbes been concerned first and foremost with the beggar's relief, the good that he would have wished to the beggar would have belonged to Hobbes as well. His union with the beggar, a communion of persons, would have extended his own being, thereby fulfilling his own existential emptiness. Such is the power of love. And such is the nature of human fulfillment, for men and women alike. Our religious equality consists precisely in our ability, and our need, to exercise selfgiving love. When we do, we come into communion with each other and with the Divine Communion of Father, Son, and Spirit. "For God is love, and he who lives in love, lives in God, and God lives in him" (I Jn 4:I6).

In section 10, "He Shall Rule over You", Pope John Paul II uses this same distinction between self-giving love and desire to interpret the Adam and Eve story. The first couple misused their precious freedom to reject the dignity of their vocation. They were created as a "unity of the two". But they freely chose desire over love. The penalties of that fateful choice constitute the fallen state into which all of us are born, a state in which, as God said to Eve, "Your desire shall be for your husband, and he shall rule over you" (Gen 3:I6). Eve's love for Adam, now desire rather than self-gift, is the refusal of her own dignity as a woman. Adam, dominating Eve rather than loving her, violates not only her dignity and vocation as a woman, but his own dignity and vocation as a man (DVW, pp. 33-41)

Taking this story as a paradigm of all human relationships, the Holy Father thus sees the two main ways in which any communion of persons can be ruptured — by desire and by domination. Since these egocentric attitudes are effects of sin, they are meant to be reversed through the process of our redemption. Thanks to the grace of Christ, we can once again become capable of love rather than desire for each other, and of service rather than domination. Our redemption will thus restore, in all interactions among human beings, the communion of persons that is our fulfillment and the glory of God.

This notion of personal fulfillment speaks directly to the basic concern that drives the American feminist agenda. Women's concern for personal fulfillment (what the Holy Father refers to as "self-discovery") (DVW, pp. 37-45 and passim) is a deep and legitimate human need. But this legitimate drive is perverted at its roots in feminism by a false view of what personal fulfillment is. The feminist movement is one facet of the individual expressivism deplored by Robert Bellah and his colleagues in Habits of the Heart. [l0] It is an egocentric urge to desire and dominate other persons instead of finding communion with them in self-giving love. For too many feminists — see, for example, the wife in the film Kramer vs. Kramer — freedom translates into the right to be egocentric, to define our fulfillment as we see fit, and to seek it without interference from anyone. If that search means abandoning husband and children, so be it. If it means acquiring power for the sake of power, so be it. If it means sexual license and abortion on demand, so be it. If it means relationships in which we use each other, or calculate devotion to each other's good on the basis of a strict costs/benefits analysis, so be it. First and foremost, we must take care of ourselves. Commitments and relationships are loose and conditional, depending directly on the benefit that we gain for ourselves.

The dynamism of the women's

movement of our time is, then, desire rather than self-giving love. The remedy

is, of course, simple — but simple does not mean easy. It is the deep conversion

that all of us sons of Adam must undergo, the conversion from desire to love,

from self-seeking to self-giving, in every interaction with every human being.

In Robert Johann's words, "An eros that is sincere . . . discovers that its vocation

is to convert itself entirely to liberality." [11]

But altruism goes against the grain of wounded human nature. And in our society,

there is a special obstacle to that conversion, wrought by the science of psychology

and pervasive of our popular culture. With a few notable exceptions (Erik Erikson,

for example), psychologists, therapists, counselors, and others regard altruism,

devotion, and service to others as masochistic, unhealthy, and harmful to personal

fulfillment. [12]

Thus love, love as wishing good to another for that other's sake and thereby coming into a personal communion with him, is not even understood in our culture. One of the major tasks of enculturating the papal vision of the dignity and vocation of women is to correct this truly basic misconception. For there are three counts on which self-giving love is not masochistic. The first (and deepest) we have already seen: the very communion of persons that such love generates. There is an unavoidable existential fulfillment for the giver of love, one built right into the very structure of love. Thus there is no possibility that self giving love might lead to self-destruction or self-abasement. It always brings us into communion with the three Divine Persons.

But there are two other ways in which self-giving love leads to fulfillment rather than destruction. Love, after all, involves giving to others not just gifts and words and time and energy, but giving our very selves. But the giving of oneself presupposes having a self to give. And so, the love that builds a communion of persons absolutely requires the personal development of its giver. Thus the Holy Father's call to women to accept the vocation of self-giving love is also a call for women's self development, a recognition of our rights to education and employment, to the discovery and use of our talents, to positions of influence and power, to care for our health and safety. The only requirement is that our self-development must have its right orientation — not self-fulfillment for the sake of the self, but self-development in order to have something to give.

And finally, self-giving love is anything but masochistic in its hope for reciprocity, the hope that those whom we love will love us in return. The operative word here is hope. Desire demands the return of love as a condition of its giving. Genuine love hopes for reciprocity without making it a condition or demand. For after all, if love is the wishing of a good to someone, and the greatest good we can wish to anyone is his or her fulfillment as a person, then we must want those we love to exercise love in their turn. And to whom might their love be directed? Why not to the one who, by loving them first, enables them to love in return? Reciprocity, far from spoiling a communion of persons, redoubles it. [13]

Such, then, is the religious equality of men and women in the dignity of our common vocation, the holiness by which we enter into the very life of God. How is this general human dignity differentiated in the two sexes, so that women enjoy a distinctly feminine dignity? Here we must look to the Holy Father's phenomenology of that action in which sexual differences are dramatically clear and undeniable — the act of sexual intercourse. When that act is what it is meant to be, it is "a great sacrament" in reference to Christ and the Church. It is then rightly called the act of making love.

A student once remarked, on learning

that impotence is an impediment to marriage and that unconsummated marriages can

be dissolved, "Gosh, I never thought the Church would put so much emphasis on

sex." In the works of Pope John Paul II, we see an emphasis that is quite new

and even more startling (until we understand it). His view of the act of making

love is the keystone of his entire sexual ethic, his family ethic, his views on

women, and his understanding of the Eucharist and the sacramental priesthood.

He sees in the simultaneous orgasm of loving spouses a uniquely intense moment

of the communion of persons. And in that action, he sees not only the epitome

of married love, but a kind of model of what all of human life should be —

ecstatic and passionate reciprocal self-abandon. [14]

The differences revealed in the act of making love are not the stereotypes, so rightly hated by feminists, of male strength and control and female weakness and passivity. But stereotypes are not invented out of thin air. They have their roots in human experience, experience that somehow becomes distorted and caricatured. Thus, men and women, as the act of making love shows, are not rivals in a power struggle, but partners — complementary partners — in a joint urge for self-abandon that makes them putty in each other's hands. Orgasm is a high point of reciprocal self-giving love. But the self-giving is different for the two spouses, different in ways that are not trivial and that cannot be overlooked. The chief difference is in male initiative and female receptivity. For the sex act even to seem to happen, a husband must act, in an energetic and obvious way, and his wife must receive his action. He exercises a kind of initiative, and she is receptive to it. But his initiative is not aggressive and oppressive. It is a headlong rush to hand himself over to his woman, lock, stock, and barrel. And her receptivity is not passive and degrading. She gratefully accepts his compliment and responds with an equally active gift in kind, rushing to hand herself over to him, lock, stock, and barrel.

For a brief moment, then, the two become putty in each other's hands, achieving a communion of persons that is uniquely intense for both of them- That uniquely intense moment is sacramental. As a sacrament, a causal symbol of their entire life together, their communion carries over, from the bedroom to the kitchen, the living room, the yard — wherever they go as they live out the promise of that moment. [15] Their special moment is also sacramental for the rest of mankind, a model for all other interactions of all human persons — in family life and business, education, health care, politics, and international relations. This momentary marital holiness is meant to characterize all of human life. For holiness is nothing more, and nothing less, than our sexually differentiated exchange of self-giving love in all of life, in ways that are appropriate to each encounter with other men, women, and children. [16]

There are, then, genuine differences between the sexes that are natural, not just cultural, and sexual, not just individual differences that might be found in people of either sex. They are differences in perceiving, judging, and choosing; differences in the exercise of self-giving love; differences for forming communions of persons. [17] They are differences in holiness and thus in personal dignity. The Holy Father thus provides a crucial element for understanding women that has been missing from the public discussion in this country; an understanding of human sexuality that neither denies nor overemphasizes the differentiation of human beings into two kinds, masculine and feminine. By taking human nature to be analogous in men and women, he shows our absolute equality with each other as persons. And yet, he gives full value to la difference, so that sex, an obvious bodily difference, is not split off from personhood but is pervasive of it. [18] Thus, equality does not mean sameness, and difference does not mean inequality. He avoids the dilemma of either treating men and women exactly alike or else making one sex inferior to the other. Thanks to this analogy, he offers a rich and attractive view of women's dignity that takes advantage of our special traits as women, and yet sets us side by side with men in a joint, complementary search for human fulfillment that is as differentiated as people are. Vive la difference!

In his

talks on Genesis, Pope John Paul II invented a wonderful phrase for human sexuality,

"the nuptial meaning of the body". He means not just the male and female genital

organs as they function in the sexual act, but a feature of the entire person

of every man, woman, and child. Sexuality is, of course, much more than a mode

of reproduction. But it is that, and that basic biological differentiation pervades

our personalities and affects everything we think and do and say. Thus, in every

human encounter, something resembling the nuptial union must occur. For our bodies

bear a meaning that is always there, to be expressed or violated, as we freely

choose either to desire or to love the people we meet in daily life. All human

interactions, even buying a paper at a newsstand, must be characterized by self-giving

love that has a nuptial character, that is marked by a fidelity and permanence

appropriate to the occasion, by sexual differentiation, and by some sort of fruitfulness

for new human life.

The Church's emphasis on sex, then, is well placed. For the great majority of the world's people, marriage and family life are the way to salvation. Even celibate people are born into families, and the quality of a family's life as a communion of persons depends directly on the quality of the sexual intimacy of the parents. What is the reason for the power, the sacramental power, of lovemaking? One reason is the unique nature of orgasm as an experience in which we are drawn out of ourselves, our attention and concern at least momentarily decentered from our fascinating egos. Any exercise of self-giving love requires that we focus attention and concern on the one we love. Regular marital orgasm builds the habit — the habit otherwise known as the virtue of charity.

But further, in order really to say a deep and heartfelt fiat to our vocation to self-giving love, we have to believe, in our bones, in the reality of love. This basic credibility of human love is not given to us at birth, nor even at baptism. We have to learn that love is real before we can begin to believe that it is the supremely real entity of our world; that God is Love. The conviction that love is real comes to us exactly as does our conviction of the reality of anything else-through our five senses. "How can they love God, whom they do not see," asks Saint John, "if they do not love their neighbor whom they do see?" (1 John 4:21). But before we can love, we must be loved, and know that we are loved, in some sort of sensory experience. [l9] Now the act of sexual intercourse is the most intense experience of the most intense of our senses, the sense of touch. Thus, sacramental spouses know, in their bones, that love is real. They feel that reality, in the very same moment in which they are drawn out of themselves and toward each other by the overwhelming pleasure of making love. Truly, such a seduction could only have been invented by a wisdom that is divine.

The Holy Father's context here is Aquinas' unique view of the body-soul makeup of the human person. Midway between a gnostic spiritualism and a crass materialism, Aquinas offers a third view, namely, that both matter and spirit, mind and body, are essential components of the human person, united so closely as to constitute a single substance or entity. For Aquinas, a man is an incarnate spirit or a rational animal. [20] This notion of the unity of the human person is crucial for understanding sexuality. For our sexual identities are central to our identities as persons. My being female, for example, is not on a par with my green eyes, my ability to teach philosophy, or other hereditary traits that I could lose without ceasing to be myself. If, at the moment of my delivery, the doctor had said, "It's a boy!" he would not have been announcing my birth. A child of the other sex would have been someone else, not I. Sexual differences, revealing the nuptial meaning of our bodies, are important to all that we think and do and say, even for those of us who never make love or never reproduce. [21]

The nuptial meaning of the female body is a certain "primary in loving" that is due to our having bodies that are apt for conceiving, bearing, delivering, and nursing babies (DVW, pp. 6I-70 and 96-102). This primacy is not, of course, the stereotypical magic of women's intuition, that supposedly mysterious gift by which we can read minds and achieve intimacy without the hard work of honest communication. But we do have a special sensitivity to persons and their needs, thanks to our having bodies that are apt for the physical closeness to another person that occurs in conception and pregnancy. Mothers are often the first to notice their children's psychological needs, for example, and wives perceive their husband's mood changes before their husbands do. That sensitivity can flower whenever persons are entrusted to us, beginning with the crucial first stage of development when all of us are entrusted to our mothers for nine months in utero. Women enjoy an incipient psychological closeness to persons, in all situations, that is rooted in our capacity for the physical closeness of pregnancy. The dignity of women, then, is located in our distinctively feminine, spousal, and maternal capacity to foster new life in other persons. With that innate, sensitive maternal insight into their individuality, we often know by a kind of instinct how to nurture their ability to love. [22]

This nuptial meaning of the feminine body, our capacity to nourish human life in a myriad of ways, also speaks to the agenda of feminism. Far from condemning us to a degrading and dull domesticity, this notion of feminine fulfillment opens wide vistas. Women's realities and women's choices are — or should be — as varied as are the modes of feminine loving. Thus we can find the dignity of our vocation, our feminine fulfillment, in any role or any action in which we can exercise our sensitive and intuitive self-giving love. One highly dignified life is that of a full-time, stay-at-home wife and mother. Domesticity, which consists in cultivating a genuine marital intimacy and in teaching children how to love in their various sexual and individual ways, is one of the most creative and demanding challenges that anyone could ask for. Other possibilities would be a single life, a widowed life, a life of vowed virginity, a sterile marriage, a life as an active or contemplative religious, a life combining career and family, a life on an invalid's bed or in a wheelchair. To feminists seeking wider roles and opportunities for women, the Holy Father's vision offers a strong basic principle: whatever women are physically and psychologically capable of doing as an enactment of self-giving love is a legitimate occasion of the dignity and vocation of women. Thus all roles in Church and society that women can lovingly fulfill ought to be open to us. [23]

This principle

brings us, of course, to the flash point of feminist anger against the Pope —

his insistence that the ordained priesthood be open only to men. It is no accident

that women's ordination is such a flash point, because it is the focus of clashing

views on human sexuality. For those who insist on absolutely everything being

open to women, sexuality has no personal importance. It is relegated to a mere

physical attribute that is significant only for reproduction. But for the Holy

Father, sexuality is not just central to what we are as persons. It is also central

to the sacramental life of the Church, especially at the point where three sacraments

— matrimony, Eucharist, and orders — come together to provide the grace

by which human communions of persons are drawn into the Communion of Father, Son

and Spirit in the Trinity. The need for a male priest as a requirement for the

sacramental symbol of the Eucharist, brings us back to the act in which the differentiation

of the sexes matters the most and is dramatically evident-to the human marital

act, the act of "making love". Here is the "great sacrament in reference to Christ

and the Church". Male initiative and female receptivity are especially important

in the Eucharist, in which the priest reenacts the marital love of Christ the

Bridegroom for his Bride, the Church. In the Eucharist, the Divine Bridegroom

gives himself up for his Bride and becomes one flesh with her. Thus, matrimony,

the "great sacrament" of which Saint Paul speaks in Ephesians (5:32), while it

does represent and effectively cause the presence of Christ for husband and wife,

is but a faint and distant image of that divine marital act.

In this most marital of all marital acts, the initiative is entirely with the Divine Bridegroom, who "first loved us while we were yet sinners" (1 Jn 4:19). That love is received then, by the free, grateful receptivity of the human persons who are the collective Bride, as we respond by our gift of ourselves to Christ, "giving up our bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and acceptable to God" (Rom 12:I). This divine marital love, in which the Son of God makes himself putty in the hands of sinners needing redemption, is the heart of the sacrifice of the Eucharist. Its counterpart is our acceptance of that gift, by which we make ourselves putty in the hands of Divine Love.

The sacramental symbolism of bride and bridegroom in the Eucharist is no small matter, for our sacraments are not just symbols. They are symbols that cause what they signify, cause it precisely by signifying it. Thus the accuracy of the symbols is all-important. The pouring out of divine marital love in the Eucharist, then, requires that the human symbol-the visible, audible, tangible enactment of that outpouring of divine love — be accurate and clear. Otherwise, it will not effectively cause or realize that love, the love of the Divine Bridegroom for his Bride.

We have not lost the principle that all roles and actions which women are physically and psychologically capable of performing should be open to us. But that principle has to be coupled with the sacramental nature of human sexuality. For the priest, as "another Christ", must be able to re-present, in what he is as a person, the initiating love of the Son of God who is also the son of Mary. He must, in other words, be a "he", not a "she". His body must have a masculine nuptial meaning. He must have male perceptions and judgments, male love, male personal identity. A woman cannot, by reason of her physical and psychological makeup, stand in the place of the Bridegroom in the Eucharist, any more than a wife can exchange roles with her husband in the act of making love. The question of women's ordination is not, then, a question of equality, of justice or rights, or of roles in a social organization. It is a question of what is and what is not ontologically possible, given the sacramental symbolism of human lovemaking and of the Eucharist. Were a woman to play the role of the priest in the Eucharist — and role-playing is all that she could do — the effective power of the sacramental symbols would fail. Words would be spoken, gestures performed, but nothing real would happen. [24]

Jesus' selection of male apostles to be his priests was not, then, a culture-bound, sexist act but a fully enlightened choice that suited his sacramental purpose (DVW, pp. 87-90). His establishment of a male priesthood was no denigration of women. We are still the religious equals of men, equally dignified, equally beloved as persons, equally capable, with our feminine primacy in loving, of the holiness to which all of us, men and women, are called. In fact, holy married women are models for priests in their search for holiness as celibate men.

The analogy between religiously equal male and female per sons casts light on other feminist demands for equality with men in social, economic, and political life as well as in ecclesial roles other than the ordained priesthood. For religion, in the Holy Father's thought, is not just one area of human life among others; it is the basis of economic, political, social, and ecclesial life. All of human life, all of human action, is meant to bring us into communion with each other so that we might thereby enjoy communion with the Blessed Trinity. Thus all of human life is religious and must be governed by the laws of love. There is no room for the slightest sexist discrimination anywhere in human life. But the equality of men and women is an analogous one, so that the differentiation of the sexes must not be lost, not in any of our behavior, any of our laws, any of our customs and traditions. The primacy in loving that is central to our dignity and vocation as women must be treasured, developed, and institutionalized. Our laws, then, must somehow allow for the difference between the sexes, and the ERA demanded by the feminists would have been a tragic mistake. To give only one example, women need laws providing special help when they are left to cope alone with the difficult situations that men and women create together. The Holy Father's heart goes out to such women, those trapped in the poverty of single parenthood or in the psychological aftermath of abortions, for example (DVW, pp. 53-55). We might question, on the same basis, laws that would place young children into daycare so that their mothers might work away from home. It might be better for the dignity and vocation of abandoned or widowed mothers if they were paid to stay home and care for their children.

The Holy Father's letter returns at the end to Mary as the epitome of feminine holiness and model for all persons of both sexes. What is decisive for her dignity and vocation is decisive for us all. As equal persons, men and women alike are called to communion with the triune God, in and through our communion with each other. Throughout the Bible, from Eve to the woman of Revelation 12, feminine receptivity shows men the way to communion with God. For before God we are all receptive, all passive to the initiative which brings us his love and calls us to make a return in kind, with our own "Be it done unto me according to thy word."

Pope John Paul II ends his meditation with two fervent prayers. The first is a prayer of thanks, on behalf of the entire Church — thanks to God for the gift of women, for the Incarnation and other great deeds of feminine holiness throughout the centuries. The second is a prayer to Mary, that she will obtain for all other women the grace of finding the dignity of their vocation, the vocation to love.

It seems appropriate, since we are gathered here in the heart of Manhattan, to end these considerations with an item from The New Yorker magazine, dated April 23, 1990. It is a poem about that human experience on which the Holy Father's teaching on women finally rests, the sacramental lovemaking of Christian spouses. The poem, written by Mary Stewart Hammond, speaks of male initiative that is anything but aggressive or oppressive, and of female receptivity which is anything but passive or degrading. It speaks as well of death, and resurrection, and even of ascension. Its title is "Making Breakfast".

There's this ritual, like a charm,

Southern women do after their men

make love to them in the morning.

We rush to the kitchen. As if possessed.

Make one of those big breakfasts

from the old days. To say thank you.

When we know we shouldn't. Understanding

the act smacks of Massa, looks shuffly as

all getout, adds to his belly, which is bad

for his back, and will probably give him

cancer, cardiac arrest, and a stroke. So,

you do have to wonder these days as you

get out the fatback, knead the dough,

adjust the flame for a slow boil,

flick water on the cast-iron skillet

to check if it's ready and the kitchen

gets steamy and close and smelling

to high heaven, if this isn't an act

of aggressive hostility and/or a symptom

of regressed tractability. Although

on the days we don't I am careful

about broiling his meats instead of

deep-fat frying them for a couple of hours,

dipped in flour, serving them smothered

in cream gravy made from the drippings,

and, in fact, I won't ever do

that anymore period, no matter what

he does to deserve it, and, besides, we are

going on eighteen years, so it's not as if we

eat breakfast as often as we used to,

and when we do I now should serve him

oatmeal after? But if this drive harkens

to days when death, like woolly mammoths

and Visigoth hordes and rebellious kinsmen,

waited outside us, then it's healthy, if

primitive, to cook Southern. Consider it

an extra precaution. I look at his face,

that weak-kneed, that buffalo-eyed,

Samson-after-his-haircut face, all of him

burnished with grits and sausage

and fried apples and biscuits and my

power, and adrift outside himself,

and the sight makes me feel all over

again like what I thank him for

except bigger, slower, lasting, as if,

hog-tied, the hunk of him were risen

with the splotchy butterfly on my chest,

which, contrary to medical opinion, does not

fade but lifts off into the atmosphere,

coupling, going on ahead. [25]

Endnotes:

- Pope John Paul II, On the

Dignity and Vocation of Women (Boston: Daughters of St. Paul, 1988). Hereafter

cited in the text as DVW, with page numbers following. Back to

text.

- Karol Wojtyla (Pope John Paul II),

Love and Responsibility, trans. by H. T. Willets (New York: Farrar, Straus

& Giroux, 1981). Back to text.

- See

Mary G. Durkin's summary of these 56 weekly addresses, Feast of Love: Pope

John Paul II on Human Intimacy (Chicago: Loyola University Press, 1983). Back

to text.

- Pope John Paul II, The Role

of the Christian Family in the Modern World (Boston: Daughters of St. Paul,

1981). Back to text.

- Joseph

Cardinal Ratzinger, Instruction on Respect for Human Life in Its Origin and

on the Dignity of Procreation (Boston: Daughters of St. Paul, 1987). Back

to text.

- The questions on love are in

the Summa Theologiae, I-II, 26-28. For an excellent exposition of their doctrine,

see Robert Johann, S J., The Meaning of Love (Glen Rock, NJ.: Paulist Press,

1966). Back to text.

- See

note 2, above. Back to text.

- Both

terms are problematic in English. Self-giving love, as we shall see, has false

connotations of masochism. And desire refers to many legitimate affections as

well as the possessive domination or use that the Holy Father has in mind. Back

to text.

- This story, which Hobbes tells

on himself, is reported in John Aubrey's Brief Lives, ed. Oliver Lawson

Dick (London: Secker and Warburg, 1949), p. 157. Back to text.

- Robert Bellah, Habits of the Heart (Berkeley:

University of California Press, 1985). Back to text.

- Johann, The Meaning of Love, p. 78. Back

to text.

- See the fine assessment by

Paul C. Vitz, Psychology as Religion: The Cult of Self-Worship (Grand Rapids:

Eerdmans, 1977). Back to text.

- See

Saint Thomas Aquinas on the "mutual indwelling" of lover and beloved, Summa

Theologiae, I-II, 28, 3. Back to text.

- See

"Marriage and Marital Intercourse" in Wojtyla, Love and Responsibility,

pp. 270-78. Here Professor Wojtyla recommends to Christian spouses an effort to

achieve simultaneous orgasm and even the use of a sex therapist, should such help

be needed, for this orgasmic communion of persons is the heart of the sacrament

of matrimony. Back to text.

- See

Embodied in Love (New York: Crossroad Press, 1983), co-authored with C.

A. Gallagher, S J.; George A. Maloney, SJ., and Paul F. Wilczak.

Back to text. - The contagion of love,

through its credibility in loving spouses, is one of the important themes of The

Role of the Christian Family in the Modern World. John Paul II expects the

love of sacramental spouses to spread to the entire world, thus creating a "civilization

of love". Back to text.

- For

a modest attempt to identify some natural sexual differences, see my "Abortion

and Intimacy", America 140, (May 26, 1979), pp. 429-32.

Back to text. - See DVW, pp. 33-41 and

79-92, and my article "Pope John Paul II's Letter on the Dignity and Vocation

of Women" in Communio International Catholic Review XVI, 2 (Summer 1989),

pp. 220-26. Back to text.

- For

a brief and readable account of how the sense of the reality of love grows throughout

the stages of the life cycle, see Rev. David P. O'Neill, About Loving (Dayton,

Oh.: Geo A. Pflaum, Publisher, Inc., 1967). O'Neill parallels Erik Erikson's view

of the eight stages of life with passages from the Bible and with wonderfully

apt photographs. Back to text.

- For

an integral philosophical and theological Thomistic view of the human person,

see jean Mouroux, The Meaning of Man (Garden City: Doubleday and Co., Inc.,

1961). Back to text.

- For

a striking study of the nuptial meaning of Jesus' body as seen by Christian painters

of the Renaissance, see Leo Steinberg, The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance

Art and in Modern Oblivion (New York: Pantheon Books, 1983). Back

to text.

- See my article "Pope John Paul's

Letter", pp.219-21. Back to text.

- See

my "The Roots of Liberation", Communio International Review VII, 3 (Fall,

1981), pp. 250-76. Back to text.

- The

basic principles of this sacramental theology were set forth in two articles by

Donald J. Keefe, S J.: "Biblical Symbolism and the Morality of in vitro Fertilization",

in Theology Digest 1974, pp. 308-23; and "Sacramental Sexuality and the

Ordination of Women", Communio International Catholic Review V, 3 (Fall,

1978), pp. 228-51. Philosophical support for Keefe's views can be found in my

"The Ordination of Women: A Philosopher's Viewpoint", The Way 21, 3 (July,

1981), pp. 221-24. Sister Sara Butler, M.S.B.T., once a prominent supporter of

women's ordination, now sees Aquinas' anthropology as central to the question,

and calls for a sympathetic reading of the Vatican's 1977 "Declaration on the

Question of the Admission of Women to the Ministerial Priesthood". See her "Second

Thoughts on Ordaining Women", Worship 63, 2 (March, 1989), pp. 157-64.

Back to text.

- Mary Stewart Hammond, "Making Breakfast", The New Yorker, April 23, 1990, p. 40. Back to text.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Rousseau, Mary. "Pope John Paul II's Teaching on Women." In The

Catholic Woman 3 (Ignatius Press, 1990): 11-31.

Reprinted by permission

of The Wethersfield Institute.