Pain as Sharpener

- FREDERICK W. MARKS

There is a saying that when the going gets tough, the tough get going.

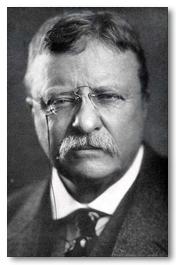

|

Theodore Roosevelt, Jr.

(1858-1919) |

Juliette Low, founder of the Girl Scouts, is a case in point. On her wedding day, a grain of rice thrown on the bridal party lodged in her ear. Doctors tried to remove it, but in the process, they pierced her eardrum, making her hard of hearing for life. It was a harbinger of things to come. Not only did her husband turn out to be a philanderer, but he also left his entire fortune to a mistress. Juliette could have fallen to pieces. Instead she found a new channel for her love and spent herself for a worthwhile cause.

Another girl was barely six when her father and mother parted company. The stigma attached to divorce, combined with poverty, forced her family to move time and again. In spite of such obstacles, however — or perhaps on account of them — the girl grew up to be spiritually robust, and eventually she entered a convent. Some years later, she was severely injured when a heavy-duty scrubbing machine spun out of control. She managed to get back on her feet again, but the pain in her legs and back was so severe that it forced her to wear braces. The name of this remarkable woman, who went on to found monasteries in the South, along with a Catholic media ministry that has inspired millions, is Mother Angelica.

There will always be some who use suffering as an excuse to justify nonbelief. Why, they want to know, does God allow pain to torment good people if He Himself is all good and all powerful? The question cuts deep, and there is really no answer for those bent on skepticism. As Christians, though, we find a definitive answer in Jesus, who suffered the worst pain the world has ever been able to inflict in order to save the world. God could have accomplished His purpose any way He wanted. But He used suffering as an instrument to show us the way.

In the Old Testament, the immolation of the lamb was a sign of salvation. In the New Covenant, Jesus is, of course, the Lamb of God. And in both cases, the principle is the same. As St. Paul wrote, "Without the shedding of blood there is no forgiveness of sins" (Heb. 9:22). Perhaps this is why the deaf, when they refer to Our Lord in sign language, point to the palms of their hands and to imaginary nail prints of the Crucifixion. Such marks are of the essence, for our religion was born in pain.

Along with Christ’s example, there are innumerable case studies indicating that pain can lead to greatness. Babe Ruth, the home run king, struck out 1,300 times before he reached the Hall of Fame, and Abraham Lincoln lost more elections than he won. History suggests further that suffering is the gateway to creativity. It is highly doubtful that Charles Dickens would have written David Copperfield or Oliver Twist had he been financially secure. And the same may be said of others. Walter Scott, like Dickens, was forced by the pinch of penury to harness his literary talent. Both men were indebted to debt.

The Rough Rider, about to deliver a speech, paid little heed to the bullet. Indeed, he insisted on delivering the entire text of his address with a slug buried deep in his chest! |

Next in importance to indebtedness as a catalyst for greatness comes disability. In the cases of Thomas Edison, Alexander Graham Bell, and S.F.B. Morse, it could well be argued that without the deafness that plagued members of the families of all three men and vigorous efforts on the part of each to overcome its effects, none of them would have made their mark. The light bulb, the phonograph, and the Morse code are all products of persistent effort to deal with a handicap.

Third and fourth on our list as agents of progress are melancholy and death once again entirely unlikely from a strictly secular point of view. How many of us are aware that the most famous of all waltzes and the most beloved of all marches owe their existence to one or another form of sadness? Johann Strauss conceived The Blue Danube while meditating on a poem about a woman "rich in sadness," while John Philip Sousa was mourning the death of a close friend and business associate when he composed his Stars and Stripes Forever.

Occasionally, one comes across a saga in which almost all of the above elements come into play. Such is that of Theodore Roosevelt. TR would never have become a judo expert and boxing champion, much less McKinley’s successor in the White House had it not been for asthma. As a child, he hovered at death’s door during chronic fits of wheezing. But he would not admit defeat and what emerged from his decades-long battle for fitness was an outstanding physique, along with sterling character. When a would-be assassin fired point blank at him in 1912 during his "Bull Moose" campaign, his bullet met three objects along its path: a speech manuscript, an eyeglass case, and a powerful set of upper-body muscles developed during Roosevelt’s childhood fight for survival. The Rough Rider, about to deliver a speech, paid little heed to the bullet. Indeed, he insisted on delivering the entire text of his address with a slug buried deep in his chest!

This first Roosevelt, not to be confused with distant cousin Franklin (FDR), was one of the last of the Renaissance men: big game hunter, cowboy, soldier, police commissioner, governor, author of dozens of books, historian, natural scientist, and, not least of all, family man. And just as his career was multifaceted, so too was his suffering.

As a freshman legislator in the New York State Assembly, he received word that things were sadly amiss at home. Boarding the first train to Manhattan, he proceeded to lose through death the two most important women in his life, his wife and mother, within a matter of hours. Such pain, excruciating for a man of Roosevelt’s affectionate nature, might have caused him to fall prey to self-pity. But not TR, who retreated to the Dakota Badlands, got back on his feet, and forged full steam ahead.

Pain, when it rubs against character, acts as a sharpener. |

Earlier, during his years at Harvard, he had taught Sunday school, and to the end of his life, he would stress the importance of weekly church attendance. Thus sustained by religious faith during the darkest days of his life, he was able to rise meteorically to the governorship of New York and from there to the Oval Office, from whence he inaugurated the Square Deal, instituted the National Park System, and won the Nobel Peace Prize.

Pain, when it rubs against character, acts as a sharpener. Would Roosevelt have joined the ranks of the immortals without being hammered nearly to death on the anvil of "misfortune"? He might have done well. But would he have achieved wonders? Fyodor Dostoevsky might have been a good man had he not been sentenced to hard labor in a Siberian prison camp. But years of toil, combined with meditation on the Bible, the only book allowed in his cell, had a powerful effect. This, in addition to a dramatic 11th-hour stay of execution that saved his life-a firing squad actually stood at the ready converted him to Christianity, and from that moment on, he soared. Crime and Punishment and The Brothers Karamazov were only a matter of time.

Not many years ago, a Peruvian hostage crisis received broad coverage in the press. Shining Path guerrillas, after seizing the Japanese embassy in Lima, held dignitaries hostage for weeks. While radical demands were negotiated, lives hung in the balance. Eventually, through the mediation of Church authorities, a logjam was broken and the captives were freed. From a purely human standpoint, the episode was terrifying. But out of it came a corps of heroes people determined to change their lives and, in particular, to dedicate themselves to their families as never before. God is in charge, and an act of terrorism, like any other act, is the raw material from which saints are made.

Some time ago, I myself reached a spiritual plateau after being hijacked on a trans-Atlantic flight by Palestinian gunmen. For a brief period following this extremely close brush with death, I experienced a heightened appreciation for the gift of life, along with an increased sensitivity to the needs of others. But then it was back to normal. My "sainthood" lasted approximately six weeks! I will say this, however: I caught a glimpse of the value of pain.

![]()

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Frederick W. Marks. "Pain as Sharpener." Lay Witness (May/June 2006): 54-55 .

Reprinted with permission of Lay Witness.

Lay Witness is the flagship publication of Catholics United for the Faith. Featuring articles written by leaders in the Catholic Church, each issue of Lay Witness keeps you informed on current events in the Church, the Holy Father's intentions for the month, and provides formation through biblical and catechetical articles with real-life applications for everyday Catholics.

The Author

Frederick W. Marks is the author of six books, including A Catholic Handbook for Engaged and Newly Married Couples, Velvet on Iron: The Diplomacy of Theodore Roosevelt, and A Brief for Belief: The Case for Catholicism. A frequent contributor to Homiletic and Pastoral Review, Marks has also written for This Rock and New Oxford Review. He resides in Forest Hills, NY, with Sylvia, his wife of thirty-eight years, and Mary Anne, his seventeen-year old daughter.

Copyright © 2006 LayWitness