Is One Man's Faith Another's Superstition?

- DAVID GIBSON

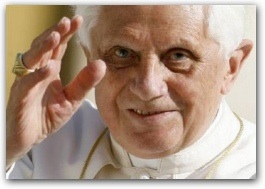

At a Mass on Saturday in Luanda, Angola, Pope Benedict tried to warn his listeners of the dangers of belief in witchcraft.

|

Though he never used that word, his implication was clear when he suggested that African Catholics should offer Christ to their fellow citizens because "so many of them are living in fear of spirits, of malign and threatening powers." He worried aloud about many Africans: "In their bewilderment they end up even condemning street children and the elderly as alleged sorcerers. Who can go to them to proclaim that Christ has triumphed over death and all those occult powers?"

Who indeed? The statement reflects a real and tragic problem in many parts of Africa, even among people who identify as Christians. Many still consult shamans and use talismans or potions for everything from fertility problems to exorcisms, while others take things a horrifying step further: Children, especially those with a physical deformity or afflicted with a disease like AIDS, are often brutalized or killed in the belief that they are possessed by evil spirits. The elderly, especially women, are also common targets. Earlier this month, Amnesty International reported that more than 1,000 people were rounded up in Gambia in a government-sponsored witch-hunt, and in Tanzania alone, at least 45 albinos have been murdered since 2007 because popular superstition holds that they are witches.

No wonder church leaders who praise the explosion of faith across Africa as the future of Christianity -- the Christian population has gone to 360 million today from eight million in 1900 -- also take pains to try to purge superstition and witchcraft from the continent. And they regularly fail, or offend. A decade ago Episcopal Bishop John Shelby Spong -- roughly Benedict's polar opposite on the theological spectrum -- was forced to apologize for referring to African Christians as "just one step up from witchcraft." What he had actually said was that African Christians have "moved out of animism into a very superstitious kind of Christianity" and have "yet to face the intellectual revolution of Copernicus and Einstein that we've had to face." But the message was clear.

In response to Pope Benedict and Bishop Spong, many would argue that religion itself is simply another form of superstition, albeit dressed up in Greek philosophy or Hebrew wisdom. And believers, even in the most well-heeled precincts of the world, are hardly in a position to criticize their African brethren. Polls show that at least half of Americans confess to being superstitious to one degree or another -- one-third believe in astrology -- and belief in various forms of the paranormal are on the rise.

But the problem is that one man's superstition is another man's religion, and vice versa. Many Protestants today still see Catholicism as being rife with superstition, most notably in the "hocus pocus" of the Eucharist (from the Latin words of consecration in the Mass, hoc est enim corpus meum, "This is my body"), while atheists and agnostics would see bien-pensant Protestants as worshiping an equally absurd form of the supernatural. It is all a matter of degree, one could argue.

And it's a good argument, given the superstitions that commingled with religion in the past and persist in the present, either in certain doctrines or in the ingrained rituals of certain followers. The distance between "prosperity theology" -- the notion that following God's commands will make you rich -- for example, and sacrificing animals to appease the gods is perhaps not as great as we'd like to think.

The difference between superstitions and religion is not only the difference between meaning and randomness, and between faith and anxiety, but also the difference between belief in a personal, benevolent God and fear of a pitiless Mother Nature, waiting to be appeased -- or exploited -- by mumbo jumbo. |

On the other hand, the history of religion could be viewed as the process, however halting and incomplete, of sshedding magical thinking to reveal truth and meaning, which are the hallmarks of genuine belief as opposed to superstition.

The difference between superstitions and religion is not only the difference between meaning and randomness, and between faith and anxiety, but also the difference between belief in a personal, benevolent God and fear of a pitiless Mother Nature, waiting to be appeased -- or exploited -- by mumbo jumbo. "Superstition" by definition "stands beyond" us, whereas religion is part of the human experience and interacts with it.

Superstition offers the illusion of control by manipulating nature or revealing her occult intent. If the spells are recited properly, all should be well. It's a big "if," however. Religion gives the promise, rather than the illusion, of hope. God does not always respond as we would like; loved ones die, livelihoods are lost. Mystery is deepened and hopefully, with faith, leads to peace rather than disillusionment. Accidental similarities between religion and magic should not lead anyone to confuse the difference in their content. Nor should the focus on witchcraft in places like Africa blind the rest of us to the lures of superstition that continue to cloud our own beliefs.

In Africa, Pope Benedict answered objections that he should leave the superstitious in peace -- arguing that it is no injustice to "present Christ to them and thus grant them the opportunity of finding their truest and most authentic selves, the joy of finding life." That could be said to be the highest goal of any true religion, as opposed to the best that witchcraft has to offer.

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

David Gibson. "Is One Man's Faith Another's Superstition?" The Wall Street Journal (March 26, 2009).

Reprinted by permission of the Wall Street Journal and the author, David Gibson.

The Author

David Gibson is the author of The Rule of Benedict: Pope Benedict XVI and His Battle With the Modern World. He worked in Rome and traveled with Pope John Paul II for Vatican Radio, produces television documentaries on Christianity for CNN, and writes frequently for various newspapers and magazines, including The New York Times, Fortune, Boston Magazine, Commonweal and America.

Copyright © 2009 Wall Street Journal