Sigrid Undset: Catholic Viking

- STEPHEN SPARROW

Compared to some of the big names of Catholic fiction, e.g. Evelyn Waugh or Graham Greene; Sigrid Undset is almost unknown: which is a perplexing state of affairs given that she wrote some of the greatest fiction of the 20th Century.

|

|

|

Sigrid Undset

(1882-1949) |

Undset was Norwegian and today her portrait graces both Norway's 500 kroner banknote and its two kroner postage stamp. She became a Catholic in 1924 and four years later was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature. Only nine women have ever received that award and Undset was the third and at 46 one of the youngest ever recipients. She is best remembered for her medieval sagas: Kristin Lavransdatter and The Master of Hestviken, although she also wrote a clutch of good quality modern day novels. But it was for Kristin Lavransdatter that she won her Nobel Award and both it and the Master of Hestviken have never been out of print since their English translations came on sale seventy years ago.

Undset's first attempt to be published ended in failure. In one of the great wrong calls in literary history, the publisher told her to forget about historical novels, "They're not your line. Why not try something with a more modern theme?" For a while she took that advice to heart and must have got the formula right, because her next novel Mrs Marta Oulie was accepted for publication. It begins with the startling confession. "I have been unfaithful to my husband." Although the book failed to make a pile of money it certainly made readers sit up and take notice.

![]()

Sigrid Undset was born in Denmark on May 20th 1882 where her father, a prominent Norwegian archaeologist, was temporarily employed. Her mother was Danish. Both parents were atheists and it was inside this milieu that Sigrid and her two younger sisters were raised, although in accord with the norm of the day, they were baptized and with their mother regularly attended the local Lutheran church. Undset senior died when Sigrid was eleven leaving the family to survive on a paltry widow's pension. At school Sigrid tended to be a loner with only one really close friend. She hated the school routine but excelled at languages. Her dream was to be an artist, however because of the family's impoverished circumstances she studied secretarial practice instead and at the age of sixteen qualified and left school to work in the office of the local power company. It was then that she began using her spare time to write. She was twenty-two when that knock-back came from the publisher but nothing daunted she kept on the case and Mrs Marta Oulie duly went on sale in 1907 followed two years later by Gunnar's Daughter and with the attendant publicity, Undset's reputation was made, enabling her to give up working for the power company to concentrate on writing.

Such was the regard in which she was now held that the Norwegian Government awarded her a travel fellowship. Her first stop was Berlin where she met and took an instant dislike to her German publishers: a dislike that was to colour her opinion of Germans for the rest of her life. From there she travelled to Rome where she found accommodation not far from the Vatican and quickly made friends with the small expatriate Norwegian community there. Among them was Anders Svarstad, an artist, thirteen years older than Undset and married to a childhood friend of her's. The couple had three children, one of whom was mentally retarded. Svarstad must have had a mesmeric effect on Sigrid because in a short time the two had fallen in love. It was of course a complicated situation that did nothing to help Svarstad's marriage and in mid 1910 Undset left Rome and returned to Norway where she worked on Jenny, a new novel that came out a year later.

There is much of Undset's own experiences in Jenny, which is the story of a struggling young woman artist, who, although engaged to be married, has an affair with her fiancé's father, becomes pregnant and gives birth to a sickly baby boy who dies six weeks later. After the child's death Jenny becomes depressed and takes her own life. The story was highly controversial especially among feminists who now considered Undset a traitor for having written about a woman destroyed by the loss of her child. They apparently thought that the author should have bowed to their simplistic demands and fitted her fiction inside feminist ideology by portraying Jenny as a woman who found fulfillment in a job.

The row over Jenny never really affected Undset who early in 1912 left Norway to return to Rome. Svarstad's marriage had now collapsed and he and Undset set up house together. Six months later they moved to Belgium where they married. From there they shifted to London where Undset's first child was born. The reality of motherhood now hit home and Sigrid discovered how difficult it is to be a good mother and write good fiction at the same time. The little family moved back to Norway where a second child was born in 1915. Tulla, as she was known was severely mentally retarded. At about this time Sigrid Undset was distressed to discover that her husband's first wife, finding herself unable to support her three children had placed them in an orphanage. Ignoring her own difficulties Undset managed to get custody of them and brought them into her own house even though it meant she now had another mentally retarded child to care for.

Near the end of 1919 the marriage of Sigrid and Anders had run into trouble and a month before the birth of their third child the couple separated. The man Sigrid had fallen in love with was not the same man she ended up in a marriage with and neither was good at compromise. But still the novels kept flowing from Undset's pen. In 1920, volume one of Kristin Lavransdatter appeared and by 1924 the trilogy was complete. Meantime Undset's life long passion with history and the meaning of life had taken a new turn. She described what later happened in these words.

"In a way we do not want to find Truth we prefer to seek and keep our illusions. But I had ventured near the abode of truth in my researches about God's friends......So I had to submit. And on the first of November 1924, I was received into the Catholic Church. Since then I have seen how a hunger and thirst of authority have made large nations accept any ghoulish caricature of authority. But I have learned why there can never be any valid authority of men over men. The only Authority to which mankind can submit without debauching itself is His, whom St Paul calls Auctor Vitae The Creator's toward Creation."

The year 1927 saw publication of The Master of Hestviken, her other major medieval saga. Undset considered this story superior to Kristin and the German Jewish Carmelite nun and philosopher Edith Stein (canonized in 1998) never tired of recommending it to any young female student whom she thought lacked a firm grip on reality.

The 1928 Nobel Literature award to Undset carried with it a cash prize valued at $US42,000.00. In today's values that would equate with more than ten times that amount. Sigrid Undset accepted the prize money and gave it all away to two children's charities. It was not as if she had no use for the money, after all, she was not exactly a wealthy woman, but it was characteristic of her innate generosity.

With the Nobel award behind her and The Master of Hestviken selling well, Sigrid turned her pen against the enemies of Christian civilization. Materialism, Atheistic humanism, Stalins Communism and Hitlers National Socialism all became targets. The Nazis reacted by banning her books. The following piece comes from an essay she wrote in 1927 entitled Catholic Propaganda in which she lambastes the welfare state, materialism, atheism and the cozy relationship between Lutheranism (the state religion) and the Norwegian Establishment. It is vintage Undset writing with the gloves off.

The worst thing about our age is that those who have the best chance to become tyrants are those who say and believe that they will only tyrannize their neighbours for their own good. We are threatened with submission to tyranny by a kind of babysitting.

|

Undset had come to Catholicism from Atheism, and on that journey looked at what Lutheranism could offer but found little to enthuse over. Her observations revealed the various Protestant Churches attempting to purify and reform themselves while at the same time trying to maintain doctrinal separation from their Catholic Mother Church. Ecumenism seemed but a distant dream and she was exasperated with evangelicals who could blithely gather, to talk solemnly about Christ, without first agreeing on what the Gospels were really saying. For Undset, dogma was the cornerstone of belief. "One cannot escape dogmas," she wrote; "and those who hold most firmly to dogmas today are those whose only dogma is that dogmas should be feared like the plague." There is a strong echo of G. K. Chesterton in that statement and she loved Chesterton, which makes me wonder if during the year she spent in London in 1913 she may well have attended some of his public lectures.

Undset saw godlessness as the enemy of civilization and with her passion for historical truth and accuracy she was well qualified to write this gem: Pre-Christian paganism is a love poem to a God who remained hidden, or it was an attempt to gain the favour of the divine powers whose presence man felt about him. The new paganism is a declaration of war against a God who has revealed Himself.

In her novel Ida Elizabeth the main character muses: "Is there something which we ought to have known and have never been told and is that why we do such terribly stupid things with our lives?" That reflection sounds very much how Sigrid Undset must have felt when looking back on her life, which in its early (atheistic) phase, was filled with moral signposts wobbling loosely in subjectivism. But, when the deception became obvious and Undset made her turnaround, she quickly became one of the most outspoken and well-known advocates for Catholicism in the whole of Europe. She pointed out the fallacy of respecting Christianity merely because of its civilizing role in history and reminded her readers that the advantages gained by any State from its Christian heritage were, "by-products which came about while the Church was pursuing her real aim that of saving souls."

Undset's researches had confirmed for her the ugly fact that in pre-Christian Europe it was the custom in most communities at the onset of winter, to kill "surplus" small children and old people by exposing them to the cold in order to preserve food supplies for the fit and the strong, and often the Church had to live with an overlap of up to a generation or more between the establishment of its mission and the gradual cessation of such pagan practices. To illustrate the regard in which Undset's historical accuracy is held; it is not unknown for University lecturers in Medieval European Studies classes to advise their students that the best way to gain an insight into the medieval period is to read Undset's sagas.

When it came to fiction, Undset dealt with life under a harsh realistic light. She wrote about people; about men and women, husbands and wives and children; and sex, especially the wrong use of sex and the lasting effects of guilt, sin and remorse. In her medieval sagas, the characters lived every day knowing that at death either heaven or hell waited for them and that only by people ordering their lives toward the good of others, could they be assured of Redemption. Outside of idiots and little children, no one of her medieval characters could ever be called innocent. But it is the special knack Undset has for portraying mothers and their children that fills the reader with awe; and as for her descriptions of Norway: its rivers, lakes, mountains; its villages, livestock, crops and weather: just close your eyes and you're there.

Coming to her Nobel Prize winning novel Kristin Lavrensdatter; anyone who has yet to read it can be envied for the treat lying in store. But be aware that at just over one thousand pages, it will require a healthy budget of time. Kristin L is about a headstrong young woman who refuses to marry the husband arranged by her father on the basis of wealth, station etc. The story follows her affair with Erland, the man she really loves, her marriage to him, the children she bears him and the vicissitudes of their life together until he is mortally wounded in a fight; after which the twilight of Kristin's life is worked out against the shadow of the plague, which marched through Europe in the 14th Century.

The following excerpt appears early in volume one and there is exquisite theology in this conversation between the Cathedral artist Brother Edvin and Kristin as a small child. Kristin has told Edvin that the dragon in his stained glass window is too small and that he could never swallow a maiden and Edvin tells her she is right and that creatures that serve the devil only seem big when they are feared. He added that if man sought God ardently; the devil immediately suffered a great defeat...

"No one and nothing can harm us child, except what we fear and love.""But what if a person doesn't fear and love God?" asked Kristin in horror, to which Brother Edvin responded.

"There is no one, Kristin, who does not love and fear God. But it's because our hearts are divided between love for God and fear of the Devil, and love for this world and this flesh, that we are miserable in love and death. For if a man knew no yearning for God and God's being, then he would thrive in Hell, and we alone would not understand that he had found his heart's desire. Then the fire would not burn him if he did not long for coolness, and he would not feel the pain of the serpent's bite if he did not long for peace."

Needless to say Undset described this little homily as sailing straight over Kristin's head.

Even earlier in the story there occurs an hilarious scene when the grandson of the priest and some young friends including Kristin, are playing 'church'. They hold a mock baptism using a wriggling piglet; the grandson then delivers a sermon in which he chides the 'congregation' for their miserly offerings and upbraids a couple for conceiving a child during Lent. All hell breaks loose when the priest himself happens past and lays into the 'naughty' children.

![]()

Kristin Lavransdatter is a trilogy that today is usually marketed in its separate volumes. However, in only the last six years a new English translation by Niina Tunnally and published by Penguin, has become available. It is a big improvement on the original with all the dialogue archaisms weeded out.

|

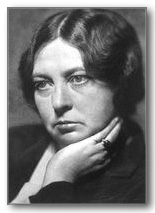

Sigrid Undset |

||||

Sigrid Undset received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1928, for her remarkable description of life during the Middle Ages in Scandinavia, the 3-volume Kristin Lavransdatter.

|

The Master of Hestviken is the story that so impressed St Edith Stein that she was forever urging it to be read by young German women. Undset herself preferred it ahead of her much acclaimed Kristin. The story chronicles the life of Olav and Ingunn whose youthful passion triggers a whole chain of murder, exile and disgrace. It has been said that sin itself is one of the main characters of the story as it entangles the people it conquers and worms its way from one moral outrage to another. The Master is another long book. This excerpt portrays the young woman Ingunn in reflective mood.

"And since God had suffered, because of the suffering her own fault would bring her; she too would desire to be punished and made to suffer every time she thought of it. She saw that this was a different suffering from any she had suffered hitherto: that had been like falling from rock to rock down a precipice, to end in a bottomless morass this was like climbing upward, with a helping hand to hold, slowly and painfully: but even in the pain there was happiness, for it lead to something. She understood now what the priests meant when they said there was healing in penance."

With her medieval sagas, Sigrid Undset has given us magnificent stories of prodigal sons and daughters, wrestling with the mystery of Christ's Redemption (the Mercy of God) all set against the backdrop of 14th Century Christendom where sin is sin, and the same as sin in our century and all of it descended from that original sin that turned the whole human race into fugitives from the Garden of Eden.

All of Sigrid Undset's intuitive knowledge of Man's potential for depravity and ungodly thirst for power were confirmed when War World II broke out. It was not long before the German Army invaded Norway and the government insisted Undset leave the country to avoid being captured and used for propaganda purposes. So, in company with other refugees she made an arduous journey, walking for much of it through mountains before crossing the border into neutral Sweden. From there she flew to Russia, then through Siberia by train and on to Japan by boat. Another boat trip took her across the Pacific to California and from there she traveled to New York where she spent the rest of the war helping the Norwegian Government in exile. What Undset did not discover until she arrived in Sweden was that her son Anders, a soldier, was shot dead by the invading Germans only a few hundred yards from her home.

After the war Undset returned to Norway and her home in Lillehammer, which the Germans had used as a brothel during the occupation. She continued writing but now found difficulty being published. Her style had become didactic, authoritarian and unappealing. Was it any wonder, considering all she had been through? On June 10th 1949 Sigrid Undset died alone at home. Her death at 67 was premature and friends identified grief as a major factor in it. In her lifetime, Sigrid Undset had brought great honour to her country and the Norwegian Government now rewarded her with a State funeral. Her home is today a national monument.

![]()

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is J. Fraser Field, Founder of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Stephen Sparrow. "Sigrid Undset: Catholic Viking." Catholic Educator's Resource Center (May, 2003).

The Author

Stephen Sparrow writes from New Zealand. He is retired and reads (and writes) for enjoyment, with a particular interest in the work of Catholic authors Flannery O'Connor, Walker Percy, Sigrid Undset, Dante Alighieri and St Therese of Lisieux. He is married with five adult children. His other interests include fishing, hiking, photography and natural history, especially New Zealand botany and ornithology. He is the author of Rahnuk.

Stephen Sparrow writes from New Zealand. He is retired and reads (and writes) for enjoyment, with a particular interest in the work of Catholic authors Flannery O'Connor, Walker Percy, Sigrid Undset, Dante Alighieri and St Therese of Lisieux. He is married with five adult children. His other interests include fishing, hiking, photography and natural history, especially New Zealand botany and ornithology. He is the author of Rahnuk.